The Recovery Period After Glaucoma Surgery

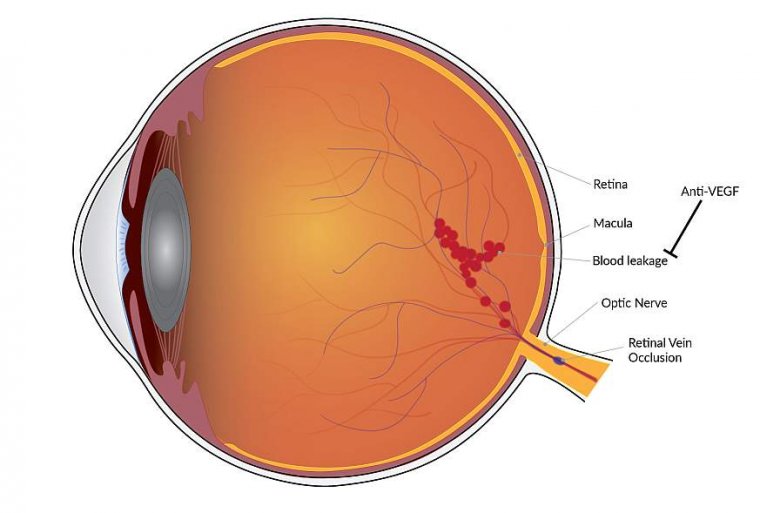

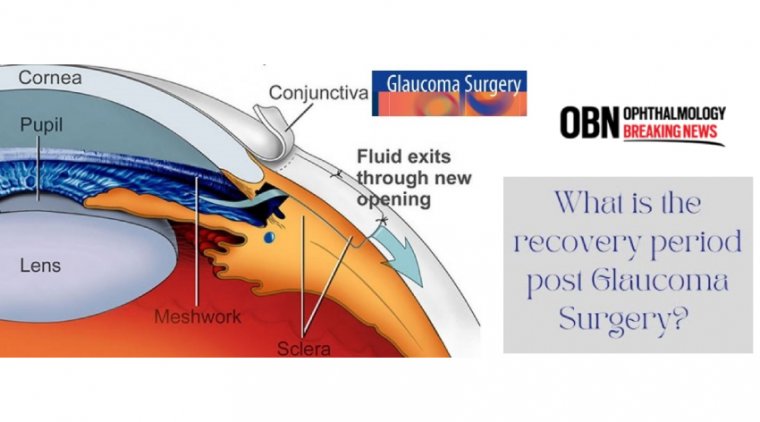

Glaucoma surgery is a procedure intended to reduce eye pressure in an effort to help stabilize vision and prevent future vision loss resulting from glaucoma.

This is accomplished by creating a new opening for fluid to drain from the eye — or, by implanting a shunt to help drain the fluid.

Recovery from glaucoma surgery varies, depending on the surgery. “Visual recovery can be rapid with less invasive procedures, such as minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), because they do not dramatically alter the structure or shape of the eye.

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of avoidable blindness, characterized by a degeneration of the optic nerve and corresponding visual field loss.

To slow down this chronic, progressive eye disease, treatment is focused on the lowering of the intraocular pressure (IOP) by restricting the production of aqueous or by increasing its outflow.

The initial approach to achieve a lower IOP is the daily use of IOP‐lowering drugs and/or one or more laser treatments. Surgery is generally considered after impermissible progression of visual field loss despite maximal tolerable medical and laser treatment.

Glaucoma surgery is not without risk and may in itself compromise visual function. It is a clinical challenge to weigh the risk and benefit in individual patients.

Glaucoma surgery is an outpatient procedure which can stabilize vision and prevent vision loss when other treatments are unsuccessful. While there are several types of surgery for glaucoma, the most common is trabeculectomy.

During this procedure, the surgeon creates an additional passage to allow fluid to drain properly from the eye, reducing damaging intraocular pressure (IOP). Advances in laser technology have made glaucoma surgery recovery shorter and reduced post-operative discomfort.

However, in some rare cases, the surgeon may still recommend conventional microsurgery, especially if the IOP is particularly high.

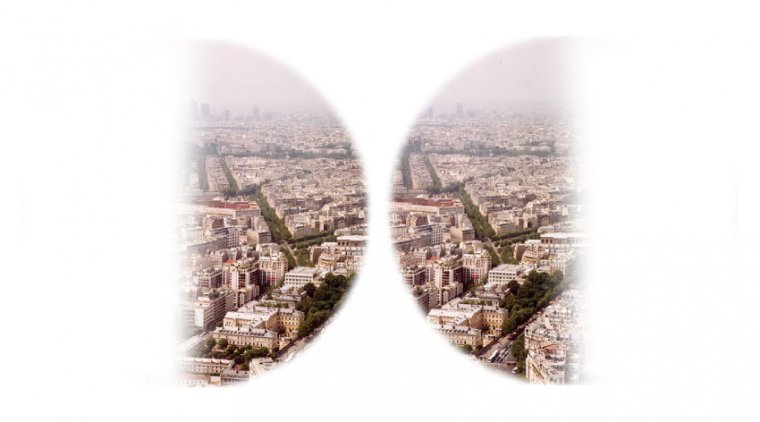

Recovery from glaucoma surgery varies, depending on the surgery. Visual recovery can be rapid with less invasive procedures, such as minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), because they do not dramatically alter the structure or shape of the eye.

More traditional surgeries can drop the pressure substantially or cause blurriness from astigmatism associated with suturing.

However, recovery can be slowed by the severity of the glaucoma and other conflicting factors, such as blood thinners or the eye’s reaction to the procedure.

Most people notice recovery in vision in days to weeks after the surgery. Instances of monthslong recovery are also possible, although very uncommon.

Most people can resume daily activities such as reading, watching TV or using phones, computers or other electronic devices within the first few days following surgery. Showering and bathing may also resume. Eye protection (a shield or glasses) is used to prevent bumping or rubbing the eye.

The marvel of micro invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS)—and the reason the doctors push them earlier in the disease course—is their safety and the predictable postoperative recovery.

In the past, there had been fewer options, most of which were more invasive. As a result, the surgeons had to delay surgery for years while patients suffered the discomfort, inconvenience, and expense of multiple medications, until finally those medications were no longer enough and surgery was unavoidable.

Now we can skip years of suffering and better manage glaucoma by making MIGS part of the treatment equation.

Historically, we were hesitant to go into the subconjunctival pathway with trabeculectomy or tube shunt because of the often slow and variable nature of visual recovery and complex postoperative management.

Instead, we waited until glaucoma progressed and the target pressure was aggressively low, often near the 10 to 12 mm Hg range.

Thankfully, with the options available today, we no longer need to wait so long to perform subconjunctival surgery for patients who need it, and with this earlier intervention, we have a better chance of achieving target IOPs because they are not so aggressively low.

Visual Recovery & Conventional Pathway MIGS

With conventional pathway MIGS, such as stenting (iStent; Glaukos, Hydrus; Ivantis), viscodilating (iTrack; Nova Eye Medical, OMNI; Sight Sciences), stripping (Kahook Dual Blade goniotomy; New World Medical), cutting/GATT (OMNI), and others, visual recovery is generally not a major concern.

Pressurizing the eye intraoperatively usually prevents intraoperative and postoperative hyphema, although if it does still occur, it usually clears up in a short period of time.

The mechanisms that make visual recovery so seamless for conventional pathway MIGS are also the reason they are not always the best option.

The episcleral venous pressure is a floor we cannot cross, so it is hard to reach target pressures below the low to mid-teens. This floor, however, also means we do not get hypotony or flat chambers, which are often the cause of postoperative vision issues.

Unfortunately, some of our patients need those lower target pressures. We also do not know where the resistance to outflow is located in our patients with glaucoma; in some, the distal channels are also collapsed or atrophied.

In these cases, we are not able to achieve the IOP control we need through the conventional outflow system. We need to turn to a subconjunctival procedure to bypass the conventional pathway.

Vision After Trabeculectomy or Tube Shunt Surgery

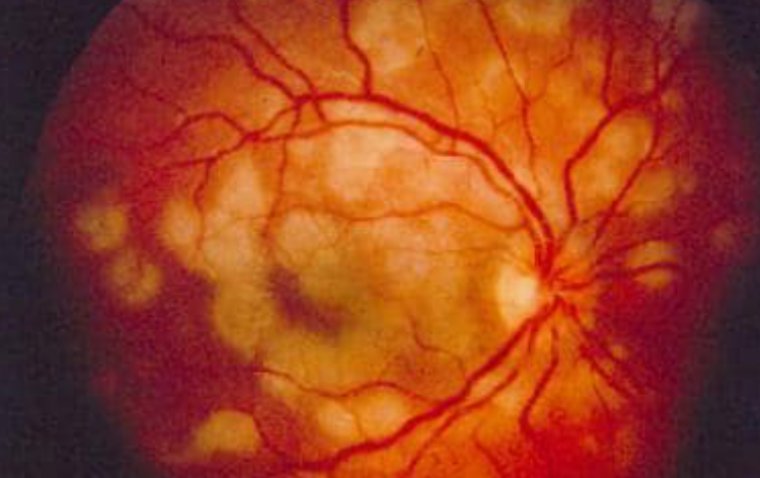

Common causes of postoperative visual acuity changes are hypotony, choroidals, maculopathy, and ocular surface problems.

With trabeculectomy and tube shunt, all of these problems are possible, so it is difficult to gauge how long visual recovery will take with each patient.

Depending on how flat the chamber becomes and the position of the iris lens diaphragm complex, a return to baseline vision may take 1 week to 1 month or even longer.

A nonvalve tube might open up in a month and a half or even earlier when the suture dissolves, and that sudden change in IOP can cause a sudden shift in chamber depth and thus a change in vision. In addition, postoperative drops can prolong recovery by destabilizing the ocular surface.

In the case of weeks or months of recovery, patients are generally not happy with their vision. IOP can be unstable, so they require multiple office visits, and they often call the office with questions about vision problems and irritation from eye drop medications.

The recovery process may still be going on when it’s time for the patient to schedule surgery on the fellow eye, which can make them reluctant to do so. As experienced glaucoma specialists, we still marvel at the high potential for variability of each step for a trabeculectomy.

We use various techniques to manage outcomes by controlling the size, thickness, and shape of the flap; titrating the flow by suture placement and tension; and trying to aggressively bring down the IOP yet prevent chambers from flattening postoperatively.

It takes time to build that comfort and skill set, and not all patients have access to surgeons who have completed 1000-plus trabeculectomy procedures.

For these and a variety of additional reasons, a less invasive and more predictable subconjunctival procedure is needed to allow access for more patients than traditional surgeries.

Faster Visual Recovery from Subconjunctival MIGS

When we want to reach a lower pressure, avoid being beholden to conventional pathways where levels and locations of resistance can be uncertain, and follow a more predictable visual recovery than we get with traditional subconjunctival procedures; subconjunctival MIGS can deliver the benefits with few limitations.

The Xen Gel Stent (Allergan) uses the same bypass mechanism as trabeculectomy, but the only outflow created is a 45 μ lumen, rather than a larger, less consistent hole in the sclera with a variable flap.

With less structural deformation of the sclera, there is less chance of flat chambers postoperatively. Even if numerical hypotony occurs, the chambers do not flatten as much because they retain greater structural integrity.

There is less concern that deformation of the eye will shift the iris lens diaphragm and cause a myopic shift or, in a pseudophakic patient, move or decenter a toric lens. Based on the approval trial, Xen has demonstrated a high safety profile with few complications.

The less invasive nature of Xen means the eye remains stable, with less inflammation in the anterior chamber and conjunctiva, often because there is no peripheral iridotomy, and if implanting from an external approach, intraoperative flattening of the anterior chamber is rare.

Since flow occurs through a single point around 5 mm posterior to the limbus, rather than in multiple directions closer to the limbus as in a trabeculectomy, the bleb forms more posteriorly and often with a lower profile, resulting in a quieter bleb and shorter-duration steroid use after surgery.

With fewer steroids and thus fewer topical preservatives, the ocular surface tends not to experience less disruption and resulting postoperative vision fluctuation.

Xen has also been shown to cause less endothelial cell loss than trabeculectomy, which could be an issue as patients get older and have other corneal risk factors.

Although postoperative bleb needling is sometimes needed, our postoperative bleb needling rates have dropped significantly (now less than 10%) with changes in technique, intraoperative confirmation of a freely mobile stent, and use of an intraoperative needling if resistance is found.

If needling is required, it is a different type of intervention than a trabeculectomy needling. We do not see a sudden drop in IOP, so there is less change in chamber depth that could affect visual recovery.

In the end, Xen reaches similarly low pressures as traditional subconjunctival surgeries with a predictable postoperative course, resulting in fewer visits (1 week and 1 month) and calls to our practice.

Because of the high safety profile and rapid visual recovery, we have now offered Xen to patients who are refractory to drops despite their level of glaucoma severity.

For instance, a patient with mild or moderate open-angle glaucoma who is taking 4 classes of medications, has a history of a previous MIGS, has stable IOP and visual folds, but is not compliant with drops would not typically have been a subconjunctival bypass candidate in the past, but this patient is now a perfect candidate for a Xen. Welcome to the interventional glaucoma mind-set.

(1).jpg)