What is X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa

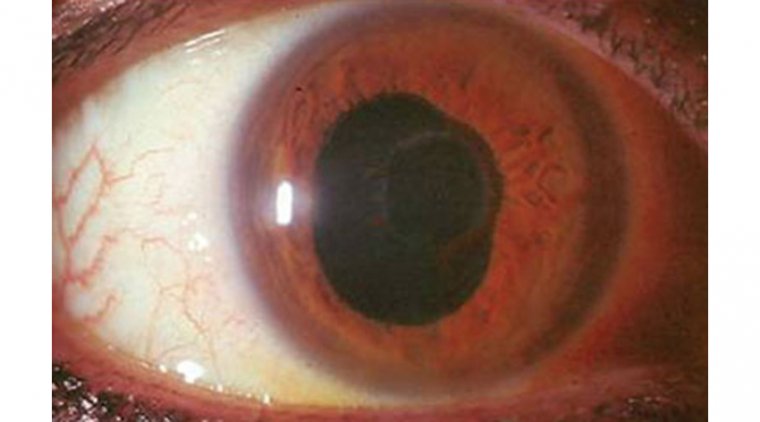

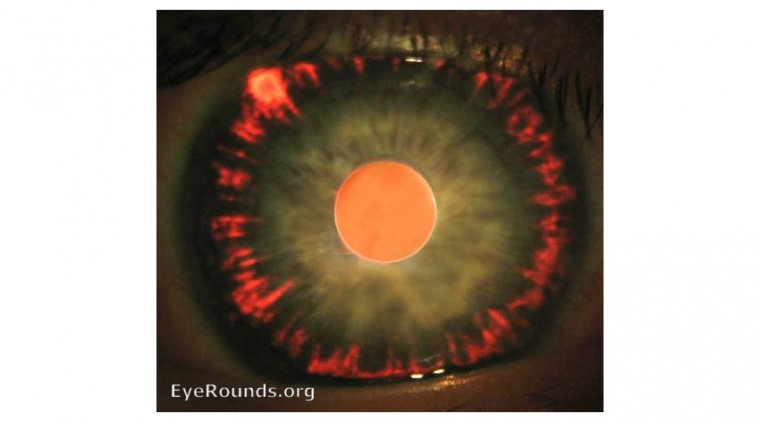

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) describes a group of rare genetic eye diseases that damage light-sensitive cells in the retina, leading to loss of sight over time.

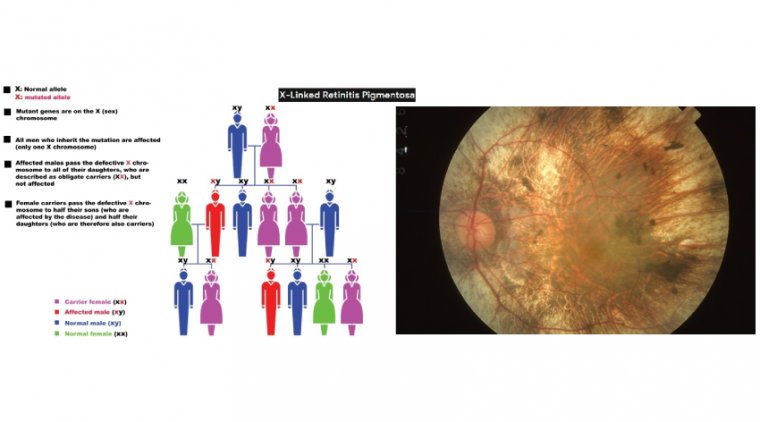

In about 10% of RP cases, the non-working gene is passed down from the mother to her children resulting in a form of RP known as X-Linked RP (XLRP).

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) gene is the most common form of recessive RP. The phenotype is characterised by its severity and rapid disease progression.

XLRP causes gradual vision loss in boys and young men. The disease begins with night blindness and is followed by a slow narrowing of the peripheral field of vision.

In general, the decline in vision (also referred to as “visual acuity”) results in a person becoming legally blind in their 40s.

Gene therapy using adeno-associated viral vectors is currently the most promising therapeutic approach.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is an heterogeneous group of inherited retinal dystrophies that affects 1 in 3000–4000 people worldwide. Although there is no ethnic specificity, mutations in particular genes are more frequent in some populations due to founder effects.

RP presents clinical variability in age of onset, progression of the disease, and secondary clinical manifestations. Generally, primary degeneration affects photoreceptor rods, causing night blindness as the first clinical manifestation.

Degeneration advances from the periphery toward the fovea, progressively decreasing the visual field and leading to tunnel vision. In the end stages of a typical rod-cone dystrophy, cones are also affected, leading to the loss of visual acuity.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) describes a group of rare genetic eye diseases that damage light-sensitive cells in the retina, leading to loss of sight over time. In about 10% of RP cases, the non-working gene is passed down from the mother to her children resulting in a form of RP known as X-Linked RP (XLRP).

Gene replacement therapies for inherited retinal degenerations have shown promise in experimental disease models and are being tested in RPE65- associated Leber congenital amaurosis and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, among others.

“Gene-independent strategies could offer promising treatment avenues for these blinding diseases,” said José-Alain Sahel, MD. According to Sahel, cones are critical to vision and preserving them may save vision in patients with inherited retinal degenerative diseases.

The focus of his team’s work, rod-derived cone viability factor, promotes cone survival by stimulating aerobic glycolysis.

In previous work, Sahel, with Saddek Mohand-Said, MD, and Thierry Léveillard demonstrated in a murine model of retinitis pigmentosa that rod transplantation delayed cone loss, which depends on functioning rod photoreceptor cells.

These findings could benefit patients with retinitis pigmentosa and other inherited retinal diseases. In addition to this research, Sahel and colleagues are involved in research to benefit patients with inherited retinal degenerations with the hope of avoiding challenges posed by gene replacement therapies, i.e., extensive genetic heterogeneity and dominant transmission.

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) is a rare inherited retinal disease for which there is not only a major unmet treatment need but also a need for greater understanding and awareness of its personal and societal burdens, according to authors of a recent article.

Published online in June 2021, the 8-page article presents the findings from a literature search and review conducted to identify and describe the clinical, humanistic and economic burdens of XLRP or RP in the United States, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom.

Although the search found a paucity of relevant literature, it is reasonable to conclude from the available evidence that XLRP clearly carries a significant humanistic and economic burden, according to Nan Li, MD, PhD, MHS. Li is the director of access at Janssen Retina DAS in Raritan, New Jersey, and a coauthor of the paper.

“XLRP causes progressive vision loss, with many affected patients becoming legally blind by age 40,” Li said. “Currently there are no approved treatments for XLRP, and unfortunately, we continue to see very limited data on this condition.”

Li also noted that additional research on inherited retinal diseases (IRD) is crucial to underscore the need for therapies and to highlight their potential to dramatically improve lives of patients and caregivers.

“Our identification of the information gaps is an important first step in assessing how best to support people with these conditions,” she said. “Therapies are currently being developed, and that is crucial.”

However, if researchers, regulators, payors and advocacy groups do not understand the needs of patients with diseases like XLRP, they may not truly realize the potential groundbreaking nature of future treatments and the myriad ways they can improve the lives of patients and their families, Li said.

Understanding the Knowledge Gap in X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa

Li said her group’s analysis of the published literature essentially shows the lack of knowledge about the many challenges patients face with early-onset and progres sive vision loss due to XLRP.

“We could not identify any studies assessing the humanistic or economic burden of the XLRP form of RP specifically,” Li said.

“Given the scarcity of studies focusing on patients with XLRP, we looked to the evidence from studies of the wider RP population to infer conclusions about the burden of XLRP, and we did find articles relating to RP in general.”

From the latter publications, it was learned that with progression of RP, affected individuals experienced a range of psychosocial, functional, physical and economic burdens. For example, the published reports showed that patients developed feelings of loss, isolation and fear.

They also suffered other negative effects on quality of life resulting from the loss of enjoyment from vision-related hobbies and pastimes.

Inability to work because of their impaired vision bore psychosocial consequences for people with RP because of loss of social support as well as economic consequences arising from lost productivity.

“Extrapolating from the findings from the RP-related research and considering first that the onset of disease is earlier for XLRP than RP, and second that XLRP is associated with more rapid progression of vision loss, it is reasonable to expect XLRP may create a greater burden for patients and their caregivers than does RP,” Li said.

Future Directions

The identification of the gap in research to characterize the burdens of XLRP is an important first step in assessing how best to support people affected by the condition.

“Our hope is to more fully understand the myriad ways the therapies currently in development for XLRP can potentially improve the lives of patients and families,” Li said. “There is so much more to uncover and know about XLRP and other IRDs and the people living with them.”

Li and colleagues are working with patient advocacy groups to generate more evidence about the cost of these illnesses.

In addition, they are looking closely at patient and caregiver wellbeing, including the emotional burden of disease. “Last year we partnered with Retina International on a study to estimate the societal disease burden and economic impact of IRDs in the United States and Canada,” Li said.

“The study found that individuals living with an IRD incur significant economic costs and reductions in their quality of life.” Li also explained that families, friends, government, employers and society end up taking on significant economic costs as well.

“As we look ahead, our Janssen team anticipates initiating more research on these topics, working hand-in-hand with our stakeholders and partners,” Li said.

(1).jpg)