Spotlight on Choroideremia: A Rare Inherited Eye Disorder

What Is Choroideremia?

Choroideremia is a rare genetic disorder that predominantly affects the choroid part of the eyes, leading to progressive vision loss. The condition is linked to mutations in the CHM gene, which is located on the X chromosome. This gene plays a crucial role in producing a protein called Rab escort protein-1 (REP-1), instrumental in the normal functioning of cells. In the case of Choroideremia, mutations lead to a deficiency or absence of REP-1, resulting in the degeneration of the choroid and retina – the layers of the eye essential for normal vision.

The inheritance pattern of choroideremia is X-linked recessive, which means the disorder predominantly affects males. Females who carry a single copy of the mutated gene are usually unaffected but can pass the condition to their offspring.

As the disease progresses, it severely impacts the function of the retina, the part of the eye that senses light and sends images to the brain. The initial symptom is often night blindness, followed by peripheral vision loss (tunnel vision), eventually leading to complete loss of sight in some cases.

Causes and Risk Factors of Choroideremia

Choroideremia is caused by mutations in a specific gene called CHM, found on the X chromosome. This gene is responsible for producing Rab escort protein-1 (REP-1), an enzyme that's vital for the normal functioning of cells. Mutations in the CHM gene lead to insufficient or non-functional REP-1, disrupting cell functions, and causing gradual degeneration of the choroid and retina, leading to progressive vision loss.

The condition follows an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. This means that males who inherit the mutated gene from their mothers will have the condition since they only have one X chromosome. Females, having two X chromosomes, will typically be carriers if they inherit one mutated gene, but they won't generally show symptoms of the disease. If a female carrier has a son, there is a 50% chance he will inherit the condition, and if she has a daughter, there is a 50% chance she will be a carrier.

While the primary risk factor for choroideremia is having a family history of the disease, the condition can also occur in individuals without any known family history due to new mutations in the CHM gene. As of now, there are no known environmental or lifestyle risk factors for this condition; it's entirely genetically predisposed. This highlights the importance of genetic counseling and testing for those with a family history of Choroideremia or other inherited eye conditions.

What Are the Symptoms of Choroideremia?

Choroideremia manifests with a gradual onset of symptoms, often beginning in early childhood or adolescence. The first noticeable symptom is typically night blindness, where individuals find it increasingly challenging to navigate in low-light conditions. This is due to the degeneration of rod cells, the light-sensing cells in the retina that enable us to see in dim light.

As the disease progresses, peripheral vision starts to deteriorate. This is often described as 'tunnel vision,' where the field of vision narrows, making it seem as though you are looking through a tunnel. Over time, this progresses to the loss of central vision as the cone cells responsible for detail and color vision begin to be affected.

The speed and extent of progression can vary widely among individuals. Some may maintain a level of central vision into their 60s or beyond, while others may experience a significant vision loss earlier.

This progressive vision loss can have a substantial impact on daily life and activities. It can make simple tasks such as reading, recognizing faces, or driving particularly challenging.

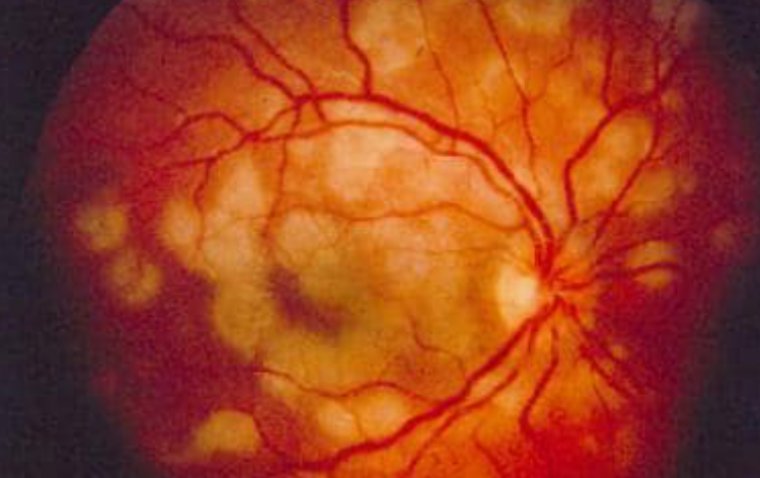

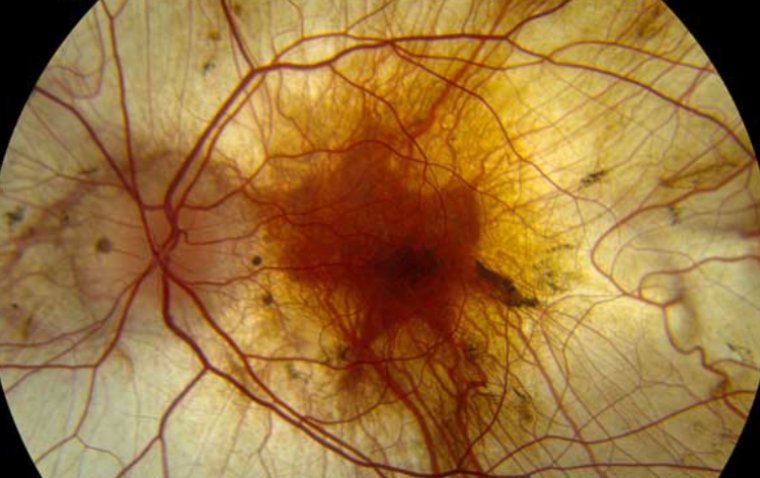

Credit: Gene Vision

How to Diagnose Choroideremia

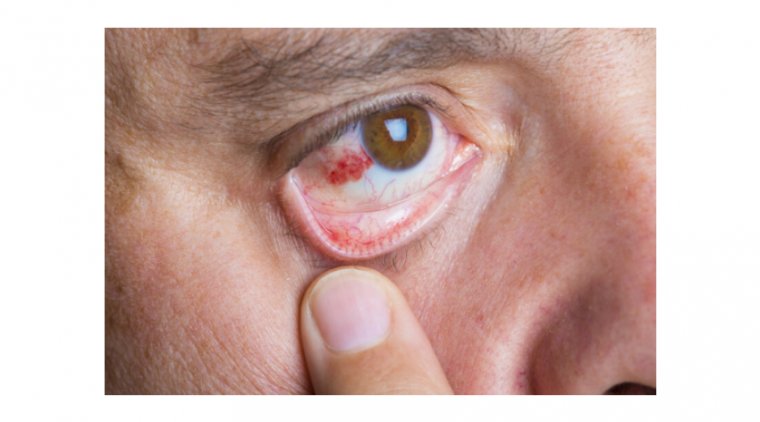

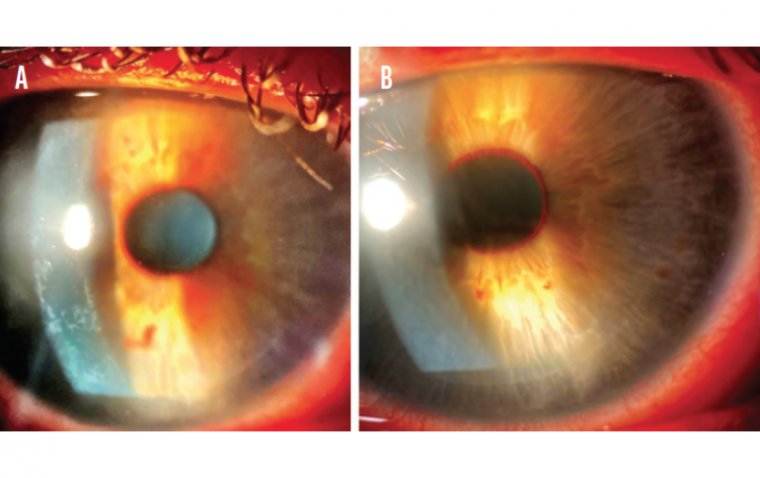

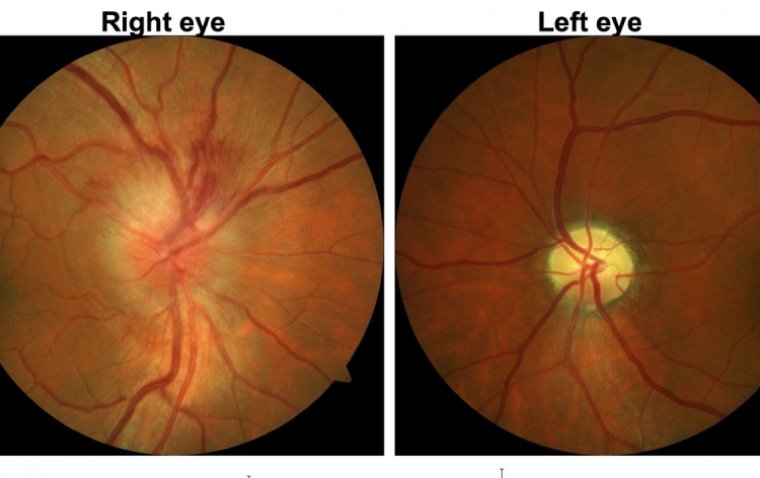

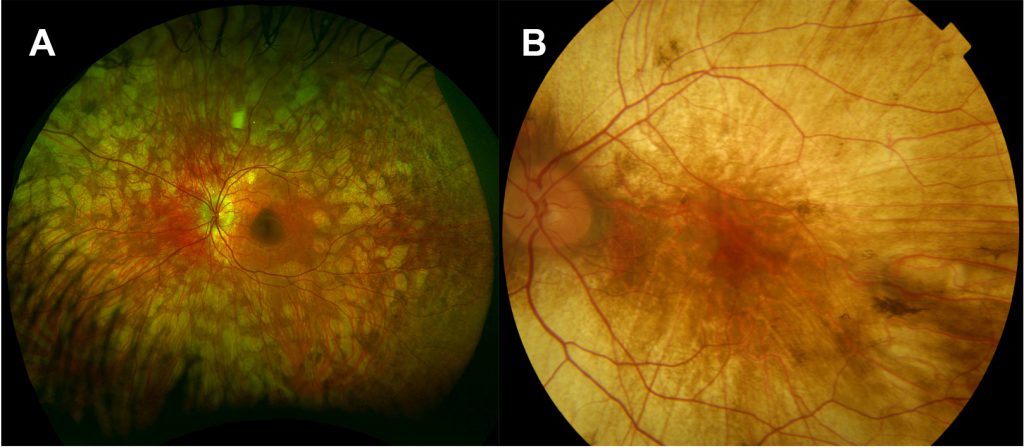

The diagnosis of choroideremia involves a thorough evaluation, often initiated with a comprehensive eye exam. An ophthalmologist may conduct a detailed examination of the retina using a procedure known as fundoscopy, which can reveal characteristic signs of choroideremia such as pigmentary changes and retinal thinning.

Visual field testing is another essential diagnostic tool that can help assess the degree of peripheral vision loss. Electroretinography (ERG), a test that measures the electrical responses of various cell types in the retina, can also provide useful information about the functional status of the retina.

However, the definitive diagnosis of choroideremia is made through genetic testing, which can identify the mutations in the CHM gene. Genetic testing is not only beneficial for confirming the diagnosis in individuals with symptoms but also for identifying female carriers or asymptomatic family members at risk.

Early detection is crucial in managing choroideremia, as it allows for timely intervention and planning for vision aids or support services. For families with a history of choroideremia, genetic counseling can be instrumental. It provides an understanding of the risk of passing the condition to offspring and the implications for family planning. Genetic counselors can provide vital information about the disease, discuss potential treatment options, and help navigate the emotional aspects of dealing with a genetic disorder.

Treatment and Management of Choroideremia

As of now, there is no definitive cure for choroideremia. However, various strategies can help manage the condition and enhance the quality of life for those affected. One exciting area of research is gene therapy, where the aim is to introduce a healthy version of the CHM gene into cells to restore the normal function. Several early-stage clinical trials have shown promising results, with treated patients experiencing a slowing of vision loss or, in some cases, an improvement in vision.

Low-vision aids can also be particularly helpful for managing vision loss associated with choroideremia. These devices, which include magnifying glasses, large-print devices, and specialized electronic systems, can assist with reading, writing, and other daily tasks.

Regular check-ups with an eye care professional are essential for monitoring the progression of the disease and adjusting management strategies as needed. Counseling and support groups can also provide emotional support and practical advice for coping with vision loss.

Ongoing research offers hope for more effective treatments in the future. Scientists are exploring various avenues, including retinal transplants, stem cell therapy, and medications that may slow or halt the progression of retinal degeneration.

Summary

Choroideremia is a rare genetic eye disorder caused by mutations in the CHM gene, leading to a progressive loss of vision. The symptoms typically start with night blindness in early childhood or adolescence and gradually progress to peripheral vision loss and, in some cases, complete blindness.

Diagnosis involves a comprehensive eye exam, specialized tests like visual field testing and electroretinography, and is confirmed with genetic testing. Early detection is critical for managing the condition effectively and planning for changes in lifestyle and vision needs.

While there's currently no cure for choroideremia, a variety of management strategies can help improve the quality of life for those affected. These include potential treatments like gene therapy, use of low-vision aids, and regular monitoring by an eye care professional. Ongoing research offers hope for new and more effective treatments in the future. Individuals and families dealing with choroideremia can find support and guidance through genetic counseling, support groups, and close communication with their healthcare providers.

(1).jpg)