Preseptal and Orbital Cellulitis

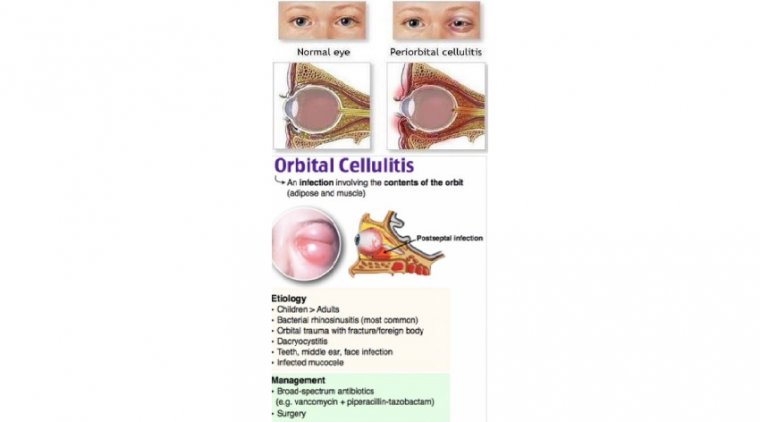

Preseptal cellulitis (periorbital cellulitis) is infection of the eyelid and surrounding skin anterior to the orbital septum. Orbital cellulitis is infection of the orbital tissues posterior to the orbital septum.

Either can be caused by an external focus of infection (eg, a wound), infection that extends from the nasal sinuses or teeth, or metastatic spread from infection elsewhere.

Symptoms include eyelid pain, discoloration, and swelling; orbital cellulitis also causes fever, malaise, proptosis, impaired ocular movement, and impaired vision. Diagnosis is based on history, examination, and CT or MRI. Treatment is with antibiotics and sometimes surgical drainage.

Orbital cellulitis is an infection of the fat and muscles around the eye. It affects the eyelids, eyebrows, and cheeks. It may begin suddenly or be a result of an infection that gradually becomes worse.

Orbital cellulitis is a dangerous infection, which can cause lasting problems. Orbital cellulitis is different than periorbital cellulitis, which is an infection of the eyelid or skin around the eye.

Symptoms include eyelid pain, discoloration, and swelling; orbital cellulitis also causes fever, malaise, proptosis, impaired ocular movement, and impaired vision. Diagnosis is based on history, examination, and CT or MRI. Treatment is with antibiotics and sometimes surgical drainage.

In children, it often starts out as a bacterial sinus infection from bacteria such as Haemophilus influenza. The infection used to be more common in young children, under the age of 7. It is now rare due to a vaccine that helps prevent this infection.

The bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and beta-hemolytic streptococci may also cause orbital cellulitis.

Orbital cellulitis infections in children may get worse very quickly and can lead to blindness. Medical care is needed right away.

Orbital cellulitis is an infection of the soft tissues of the eye socket behind the orbital septum, a thin tissue which divides the eyelid from the eye socket. Infection isolated anterior to the orbital septum is considered to be preseptal cellulitis.

Orbital cellulitis most commonly refers to an acute spread of infection into the eye socket from either extension from periorbital structures (most commonly the adjacent ethmoid or frontal sinuses (90%), skin, dacryocystitis, dental infection, intracranial infection), exogenous causes (trauma, foreign bodies, post-surgical), intraorbital infection (endopthalmitis, dacryoadenitis), or from spread through the blood (bacteremia with septic emboli).

Periorbital (preseptal) and orbital cellulitis are infections of the subcutaneous tissues of the eye. They are differentiated by the location of the infection.

Periorbital cellulitis refers to infection of the eyelid and subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum, whereas orbital cellulitis relates to infection of tissues posterior to the orbital septum. The degree and severity of infection is further graded by the Chandler’s classification.

The pathology represented does not progress chronologically, rather you can get progression to any grade within the classification. The aetiology of infection can vary from external injury, sinus disease, dental pathology or haematogenous spread.

The presentation is varied and dependent on the patient’s demographic; patients mostly complain of eyelid pain and swelling. Symptoms of visual loss, proptosis or restricted eye movements are often late signs and could indicate serious vision threatening pathology.

Diagnosis is largely clinical; however, imaging can be used when intracranial pathology or an abscess is suspected. First line treatment is antibiotic administration and treating the underlying cause; surgical drainage is sometimes required.

Understanding Periorbital and Orbital Cellulitis

Periorbital and orbital cellulitis have slightly different aetiologies; where periorbital cellulitis is typically the result of dacryocystitis or facial infection, orbital cellulitis is likely a complication of rhinosinusitits. Sixty to eighty-five percent of orbital cellulitis cases are attributed as complications of ethmoid sinusitis.

Infection of the ethmoid sinuses can easily spread through Zuckerkandl’s dehiscence, small fissures within the lamina papyracea that carry nerves and vessels, to the orbit.

Untreated, this condition results in continued progression of infection resulting in ophthalmic and intracranial complications associated with a 5-25% mortality rate.

Chandler’s classification aims to classify the different types of infection. Group 1 describes inflammation or infection confined to the eyelid, anterior to the orbital septum. Group 2 describes infection involving the orbit and post-septal tissues.

Group 3 describes infection of the post-septal tissues with an abscess within the orbital periosteum. The abscess is most likely found on the medial aspect of the lamina papyracea.

Group 4 describes an abscess in the intraconal compartment, this is a conical space formed by the posterior aspect of the globe and the extraocular muscles. Group 5 describes thrombosis of the cavernous sinus.

Periorbital cellulitis is more common than orbital cellulitis and can occur at any age, although it is more common in the paediatric patient group.

The most common causative organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Other bacterial causes include Haemophilus Influenza, Pseudomonas, Neisseria, Proteus and Mycobacterium. More rarely, fungi such as Aspergillus and Mucorales have been cultured as causes.

Clinical Presentation and Examination

The clinical history will likely involve direct questioning of the patient and a collateral history from the parent or guardian.

It is important to ascertain for predisposing risk factors from the history such as upper respiratory tract infections, dental infections, sinusitis, trauma, recent facial, ENT or ocular surgery and even insect bites.

The presence of diabetes or immunosuppression should raise the clinical suspicion of orbital cellulitis.

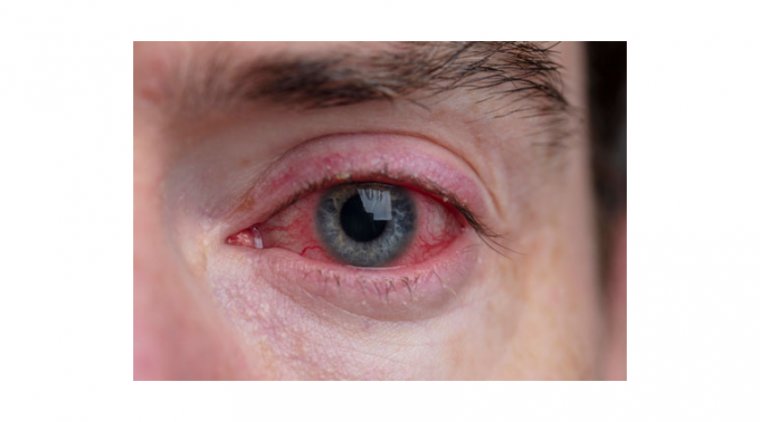

Patients will likely complain of unilateral swelling, pain and erythema of the eyelid. They may have symptoms of systemic involvement such as malaise, fever and anorexia.

Patients presenting with orbital cellulitis will likely complain of asymmetry of the eyes, chemosis, pain on eye movements, decreased vision and ophthalmoplegia.

Concurrent symptoms of headaches, neck pain, photophobia and cranial nerve palsies should raise the suspicion of intracranial pathology and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Examination of the patient should have three main components: the eye, the nose and the neurology of the patient. Examination should ideally be repeated four to six hourly to ensure no progression of symptoms.

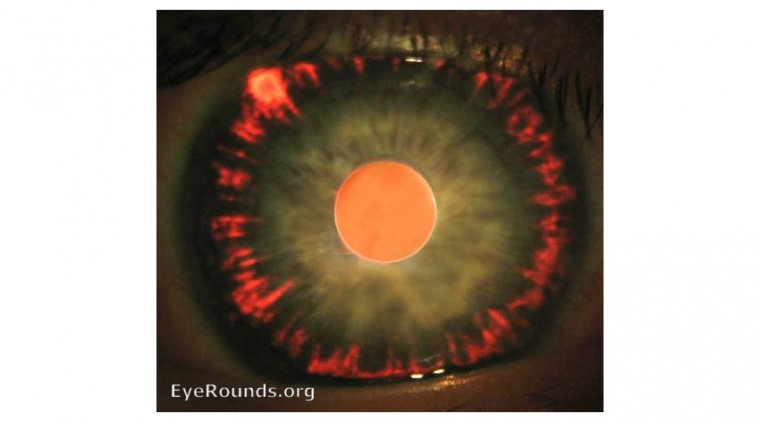

Examination of the eye should ascertain signs of chemosis, degree and position of proptosis, relative afferent pupillary defect, diplopia, visual acuity, colour vision and discrimination, ocular movements, and inspection of the optic disc.

The degree and position of proptosis can help delineate position of an abscess and can be measured using Hertel exophthalmometry. Visual acuity and colour deficits could be indicative of optic nerve involvement in Group 2 infections or retinal vein thrombosis.

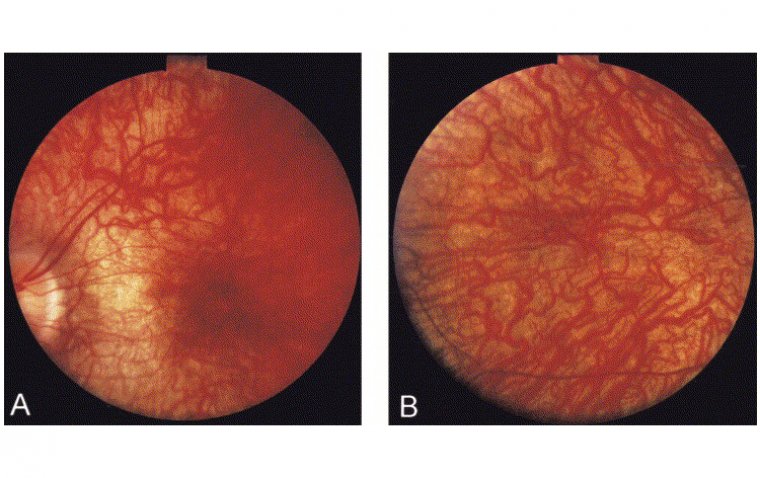

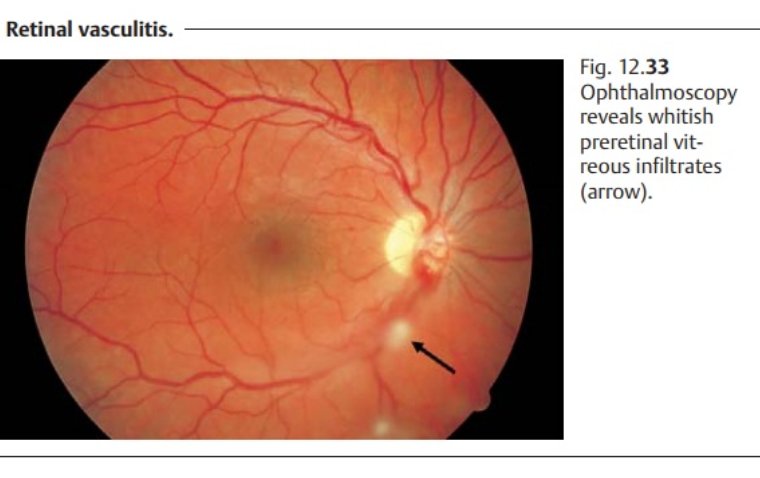

Ocular movements could be restricted due to a cranial nerve III, IV or VI palsy or restriction from an abscess. Fundoscopy can ascertain presence of optic neuropathy, retinal vein occlusion or increased venous congestion resulting in increased intraocular pressure.

Examination of the nose is usually completed by the ENT team and should include clinical endoscopic examination of the nose to ascertain site and extent of mucosal disease. Any nasal discharge noted should be swabbed and sent for microscopy and culture.

Examination of the cranial nerves can help ascertain the presence of a cavernous sinus thrombosis which has a published mortality rate of 14-79%, with half of patients experiencing morbidity in the form of residual cranial nerve palsies or blindness.

A general neurological examination should be undertaken to exclude the presence of occult intracranial pathology.

A multidisciplinary team approach should be taken in the diagnosis of orbital cellulitis. Ophthalmology, ENT and occasionally neurosurgery are involved in the care of these patients.

Orbital cellulitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis, however, certain investigations can be used to aid the diagnosis. Blood investigations can be used to confirm a systemic inflammatory response to the infection and assess the patient’s fitness for surgery.

Microbiology samples in the form of pus and blood cultures can help target a particular organism. Radiology can be utilised to confirm the diagnosis, monitor response to treatment, confirm the presence of suspected intracranial complications or help plan surgical intervention.

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast is the first line imaging modality. This is largely due to its availability, superiority in imaging bony anatomy and pathology and ease of use in the paediatric population.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be utilised to provide additional soft tissue detail without radiation exposure; however, this is more difficult to arrange for a young patient or out of hours. MRI has been shown to be superior in diagnosing intracranial complications.

It is important to note that cavernous sinus thrombosis may not be evident on CT scanning during the early stages and the clinician should consider the use of CT or MRI venography to aid the diagnosis of this condition if it is suspected.

Management and Challenges

Patients with confirmed or suspicions of periorbital and orbital cellulitis should ideally be admitted for treatment and careful observations. Medical management is often first line, unless the patient is clinically unwell, an abscess is demonstrated or there is concern regarding optic nerve compression.

Medical management aims to control and eliminate the infection. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment and are usually guided by the local microbiology guidelines before the presence of a cultured organism.

If there is evidence of rhinosinusitis; nasal decongestants, douches and steroids can aid the resolution of mucosal oedema and congestion. Response to medical therapy is monitored for 24 hours in the absence of abscess or intracranial pathology.

If there is a response to medical therapy, antibiotics are often tailored to the cultured organism and continued for a prolonged course between 10-14 days. If there is no response to treatment it is important to consider imaging or proceeding to surgical intervention.

Surgical intervention in orbital cellulitis is often similar to the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis. Endoscopic intervention allows for reinstatement of the drainage pathways, decompression and washout of pus from the sinuses.

The external approach involves the use of a Lynch-Howarth incision for an external ethmoidectomy and drainage of the abscess. Often surgical drains are left externally through the incision or intranasally.

A re-look may be warranted at a later stage if there is no clinical improvement, or a further washout or drainage is required.

Intracranial abscess formation can be the result of local or more likely haematogenous spread and may require surgical drainage and a prolonged four to eight week course of antibiotics.

Subdural empyema is more common as a complication of chronic rhinosinusitis and requires aggressive and early treatment. Medical therapy is often combined with neurosurgical drainage and evacuation of the empyema.

(1).jpg)