Dry Eye Symptoms Differences Between Day & Night

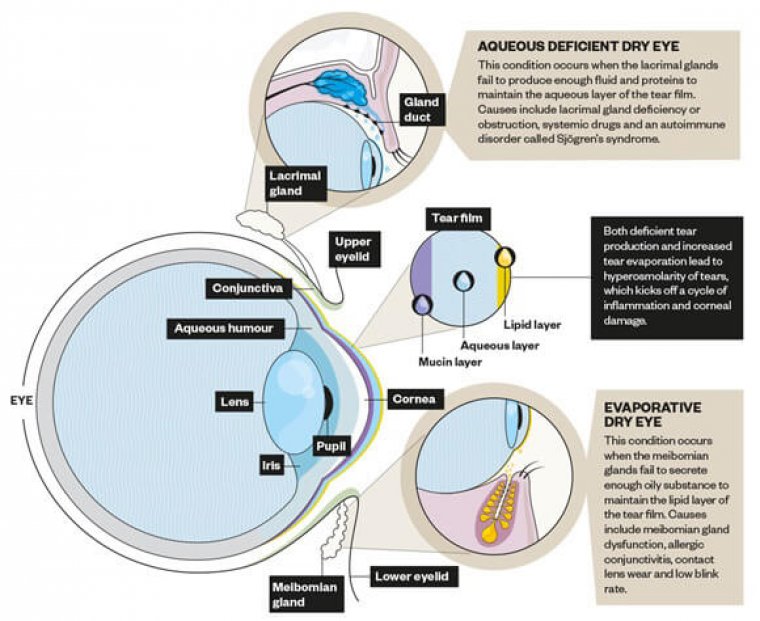

Dry eye disease occurs when your tears are unable to provide adequate lubrication, either because there’s insufficient tear production (known as an aqueous deficiency) or poor quality tears (meibomian gland dysfunction or MGD)

Gland dysfunction refers to a condition where one or more glands in the body are not functioning properly

Between the two, MGD is the more common cause of dry eyes. When tear production is optimal, the tears themselves will have an oil layer on their surface that prevents them from evaporating too quickly, and this oily layer is made by the eye’s meibomian glands.

Blockages in these oil-secreting glands result in a reduced secretion of the protective layer of tears and lead to fast evaporation.

What Causes Overnight Dryness?

It’s a common complaint, but many people that suffer from dry eyes claim that they seem to experience a flare-up of symptoms at night and first thing in the morning.

Overnight dryness is very common, and it is usually caused by a condition called lagophthalmos. In this condition, the eyelids do not properly close during sleep. Instead of completely covering the eyes, in lagophthalmos the eyelids may not fully close, or may slowly drift open throughout the night.

This condition results in a portion of the eye’s front surface being exposed for long periods of time, which causes the corneal tissue to be malnourished or damaged. Those affected by lagophthalmos usually wake up with very irritated, red, and uncomfortable eyes.

For some people, this condition is very minor and only a small portion of the lower cornea is affected. For others, it can result in damage to a large area of the ocular surface. Your optometrist can identify cases of lagophthalmos during a routine exam by closely examining your ocular surface and looking for a distinct pattern of irritation near the lower part of the eye which is most likely to be exposed.

Another theory involves how the body’s metabolism changes at night. Body temperature drops one to two degrees as bedtime nears, and metabolism slows during sleep. Because body functions slow, blood circulation slows and there are fewer nutrients reaching the eye and fewer tears being produced.

High Awareness

Awareness of the high incidence, impact on daily life, and challenges of treating dry eye disease (DED) has increased in recent decades.

Significant progress towards achieving consistency in understanding the fundamental causes of the condition, systematic diagnosis strategies, and stepwise treatment approaches have undoubtedly come from the two landmark Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop—DEWS I and II— reports.

However, with such strength of guidance, it is also easier for some surgeons to adopt a generic blanket approach, resulting in less well-focused history-taking and the more subtle clinical findings receiving too little attention.

The robustness of the fundamental recommended treatment steps means the majority of patients are still likely to experience significant benefit, often accepting the improved but residual symptoms as inevitable.

However, this is not the same as providing the most comprehensive and appropriate care. Some DED patients will experience worsening of symptoms overnight or on waking, even with effective warm compresses, lid massage/cleaning, preservative-free lubricants, and oral omega-3 supplements.

It may be that this is an unavoidable component of their dry eye condition, but it is imperative to proactively consider night-time dryness as a separate entity.

Ophthalmologists should differentiate between the worsening of dry eyes later in the day, typically associated with visual concentration tasks, and worsening of symptoms once the patient has gone to sleep and awakes in the morning.

The former is common in all dry eye patients, whilst the latter is more commonly related to night dryness. At night, body temperature drops, metabolism slows, tear production lessens, and active blinking stops, which can result in fewer nutrients reaching the ocular surface.

Most young healthy patients will cope with this, but those with existing DED or older patients have less reserve to tolerate that same drop, thus resulting in increased symptoms.

In patients with inferior localized, linear corneal± conjunctival staining despite compliance with treatment, it is important to consider two key elements.

In those with significant, poorly controlled lid margin inflammation, this staining may be the result of direct-contact toxicity from the lower lid margin to the ocular surface.

However, the possibility of nocturnal lagophthalmos is something that must be proactively considered and evidence of it specifically looked for.

Although more severe lagophthalmos may require surgical intervention, most patients will not need this. Simple exercises to encourage active, firm blinking, and massage of the upper lid to enhance closure can very quickly show subjective and objective improvements.

The use of tape to keep the lids closed at night can be effective but is often not practical in older populations, who are more likely to need to get up during the night. It is with these patients that the use of ointments at night can tip the balance of control back in our favor.

Ointments are thick and viscous, providing prolonged dwell times in the eye, coating the ocular surface, and aiding the lids to ‘stick’ together. However, this same quality can also create problems if the wrong substances are kept in contact with an already compromised ocular surface for extended periods.

The need to choose a preservative-free option is obvious. Most ointments are paraffin-based, which provides effective lubrication with a very low risk of adverse reactions. Some may contain lanolin, which is believed to aid aqueous absorption and reduce evaporation but is also a potential allergen.

Phosphate must be avoided since the risk of calcification would be even greater with the prolonged contact time of an ointment, whilst the addition of vitamin A, a natural component of the tear film important for mucosal and goblet cell health, is likely to aid recovery of the compromised ocular surface.

We always reiterate to patients the importance of a consistent and effective lid hygiene regime, specifically in the context of using an ointment, to minimize the risk of a build-up of deposits on these compromised lid margins and thus further optimize long-term success and tolerance.

(1).jpg)