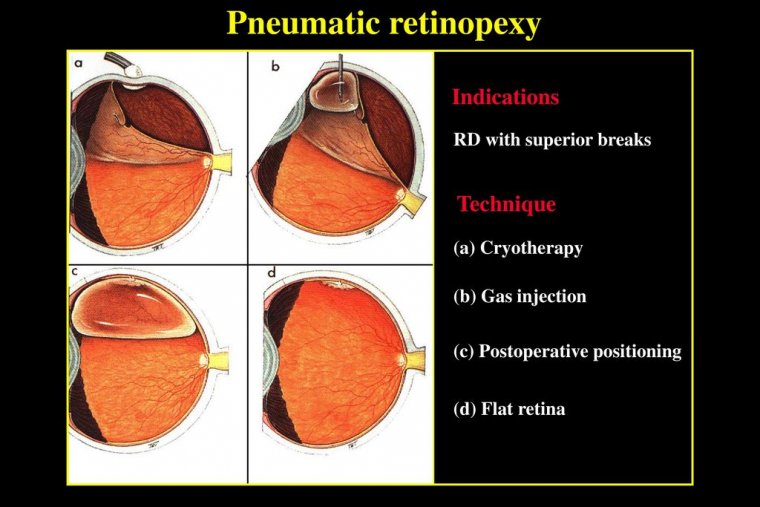

Pneumatic Retinopexy

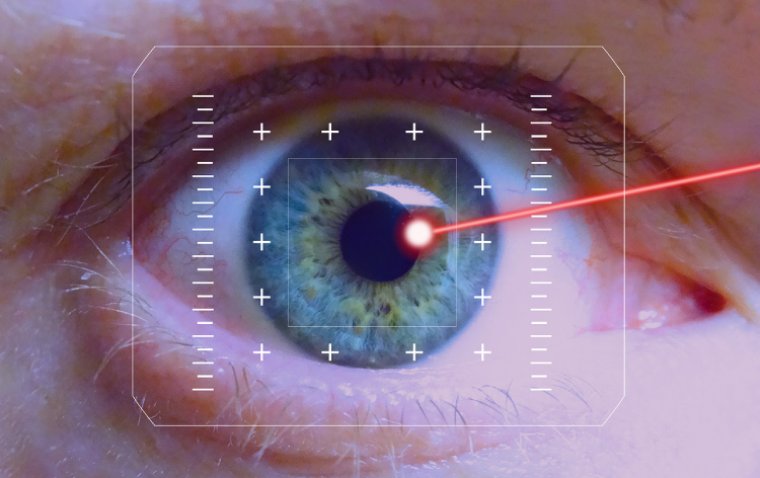

Pneumatic retinopexy is an in-office procedure used to repair certain types of retinal detachments. Pneumatic retinopexy typically treats rhegmatous retinal detachments.

The eye is numbed with anesthesia so there is no pain. A gas bubble is injected into the eye (vitreous cavity).

When the gas floats up, it pushes the retina that is detached back into proper position and also closes the retinal tear against the way of the eye at the same time, thus repairing the retinal detachment.

Cryopexy (freezing) or laser are then used to permanently seal the retinal tear to the wall of the eye.

The gas bubble goes away by itself, getting smaller and smaller over the course of 4-8 weeks, after which, if successful, the retina should be back to its proper position and the vision should be improved.

Pneumatic retinopexy is done for certain types of retinal detachments, typically for rhegmatous retinal detachments.

PnR offers superior photoreceptor integrity and less retinal displacement with better long-term visual acuity results and less vertical metamorphopsia compared with other surgical approaches.

Although the individual steps of performing PnR—namely an anterior chamber paracentesis, an intravitreal injection of gas, and laser retinopexy or cryopexy—are relatively straightforward, there is an art to performing PnR that is acquired only after performing hundreds of cases. The following are 10 tips and tricks to maximize outcomes with PnR.

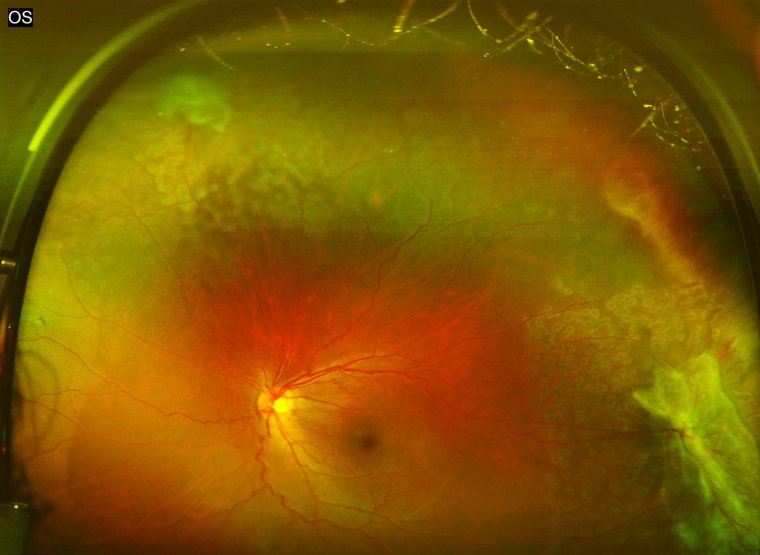

It's All About the Scleral Depressed Examination

The clinical exam is of utmost importance in PnR. It is ideal if the person who performs the procedure is the one who will follow the patient during the first week, however, if this is not possible, a second retina specialist should be able to take over if the pathology has been described in detail.

It is important to perform a careful scleral depressed examination. The surgeon needs to be aware of all the pathology in that eye, including all retinal breaks, but also areas of lattice and vitreoretinal tags.

The accuracy of the initial exam is most critical, and careful follow-up exams are also required to ensure there are no new or previously missed breaks.

Maximize the Anterior Chamber Paracentesis Volume

The size of the anterior chamber paracentesis is critical, as it dictates how much gas you can inject into the vitreous cavity. If your outpatient facility has a basic microscope in a treatment room, use it while performing the paracentesis.

This provides optimal visualization, and when the patient is lying supine, it is much more controlled than performing a paracentesis at the slit lamp. If a microscope is not available, I perform the paracentesis with the patient reclined under direct visualization.

We use a 30-G needle on a tuberculin syringe with the plunger removed. We insert the needle inferotempoerally over iris in phakic patients and over the optic from the temporal side in pseudophakic patients.

We use the plunger to apply counter pressure on the nasal limbus. This creates a dome over the needle and the firm pressure will force aqueous and liquified vitreous into the needle.

Most of the time, 0.2-0.3 cc is removed, although sometimes a much larger volume can be removed. We recommend removing as much as possible. The chamber is completely flat after this step, and the eye is generally quite soft.

Use SF6 in Most Cases

We prefer SF6 gas over C3F8 for PnR in almost all cases, as it has favorable properties that make it ideal for PnR. It reaches maximal expansion in 36 hours and dissolves in 12 days.

When we perform a PnR, we want the gas bubble to expand rapidly so it is large enough to tamponade the break(s), and we can then quickly determine if the PnR is working over the first few days. With C3F8, maximal size of the gas bubble is achieved at 96 hours.

This is a long time to wait before the bubble fully expands and before the clinician can make decisions regarding the success/failure of the procedure.

Furthermore, C3F8 lasts in the eye for 38 days after injection. In most cases, the retina is reattached fully by day 3 to 5 following PnR and the retinal breaks are well lasered.

Thirty-eight days of a gas bubble in a vitreous-filled eye following retinal detachment repair with PnR is not necessary, and it is possible that the bubble could induce other breaks. In rare circumstances in which an anterior chamber paracentesis is not possible, C3F8 gas makes the most sense.

Maximize the Size of the Intravitreal Gas Bubble Injection

We recommend injecting 0.3 cc more than what is removed during the anterior chamber paracentesis, but never less than 0.6 cc. The larger the gas bubble, the greater the chance of success.

To minimize fish eggs, while injecting gas, we always like to inject superotemporal or superonasal with the patient looking down. We insert the needle half way in and then pull back so the needle tip is barely in the eye.

The gas is injected swiftly, and the plunger of the syringe is kept pressed down while removing the needle from the eye to prevent reflux of gas into the syringe. It is not uncommon to perform a repeat paracentesis following the gas injection.

Before performing the re-paracentesis, we usually tell the patient to be face down to possibly allow more fluid to enter the anterior chamber from the vitreous cavity.

The repeat paracentesis can sometimes be challenging, as the eye is firm and the anterior chamber is shallow, but it is almost always doable. It is important to insert and remove the needle very slowly to prevent or lessen trauma and iris incarceration in the paracentesis wound.

The Steamroller Maneuver is Your Friend

The steamroller maneuver is an important part of the PnR procedure. We like to have patients position face down for the first 6 hours in macula-off detachments and for 4 hours in macula-on cases. Then, for the typical superior bullous retinal detachment, I ask the patient to raise their head by 30 degrees every hour until they are upright.

By performing this maneuver, the buoyant force of the gas bubble causes subretinal fluid to be displaced through the retinal break, reducing the amount of fluid that needs to be reabsorbed by the RPE pump.

We then ask them to tilt their head or lie on their side with the head elevated to tamponade the break. In some cases, the steamroller maneuver can be used to prevent the inferior displacement of fluid in cases with an inferior retinal break/hole in attach retina.

In these cases, the patient is first positioned on their side on a decline and then they gradually raise their head while on their side. This allows fluid to be displaced in a certain direction away from the inferior breaks of concern.

Positioning

The success of PnR is heavily dependent on compliance with positioning. That said, when you explain positioning to patients, as we do with macular hole surgery for example, most of them are concerned about their ability to do it.

Despite this, the vast majority of patients will position if their doctor stresses the importance of doing it. Patients can often misunderstand instructions. For example, in some cases, they think the positioning is just while they are sleeping.

In other cases, they think they can stop positioning after the laser retinopexy. I tell my patients to position 23 out of 24 hours per day for one week, and in some cases until the bubble disappears.

Utilize Indirect Laser Retinopexy for Most Cases and Cryopexy in Specific Situations

Although laser retinopexy is technically more challenging with gas in the eye, it is a more elegant way to treat the retinal break.

All retinal pathology, including any lattice degeneration or retinal holes/tears, should be pretreated with laser prior to the gas bubble injection. The biggest advantage of laser retinopexy is that it causes some immediate chorioretinal adhesion, as opposed to cryopexy, which can take several days.

Laser retinopexy therefore reduces the risk of the retina re-detaching if the patient becomes less compliant with positioning after the retinal break is lasered.

That said, cryopexy is very useful in specific cases, such as small pseudophakic retinal breaks that will be hard to see following PnR, PnR in children where it is unclear if they will be able to tolerate the post-PnR laser, aphakic patients where intracameral gas will impact the view, and other cases where visualization is limited.

The view almost always is worse following the gas injection, so in certain cases with poor media, cryopexy before the gas injection is much simpler.

Physicians in practices where someone else will be following the patient may also elect to perform cryopexy, so the physician taking over will not need to treat the break in a case they are seeing for the first time.

In cases where we have performed cryopexy, we may also elect to apply some laser retinopexy around the cryopexy scars and ora-ora for a few clock hours, to achieve immediate chorioretinal adhesion.

We also utilize laser in some cases to mark the retinal breaks, or laser the pars plana in the meridian of the retinal break to assist with subsequent localization once the gas bubble is in the eye.

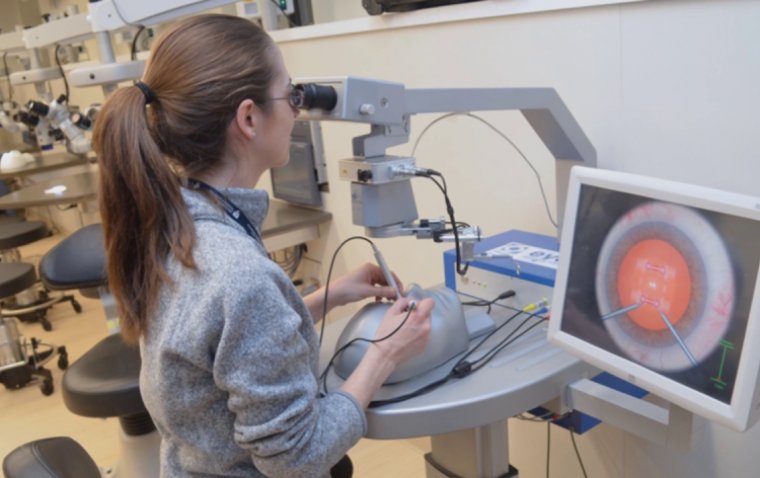

Laser retinopexy can be challenging, but we recommend getting used to doing it with an indirect laser and a 28D lens for optimal visualization.

We generally like to laser through the gas bubble, as it provides a clear, minified view. In pseudophakic patients, they can be told to look straight up to the ceiling while lying supine, and the gas bubble will cover the entire pupil and lead to a panoramic view.

Add a Second Bubble When Needed

In some cases where breaks are further apart, or perhaps in the inferior quadrants or a patient is not very compliant, a second gas bubble injection may be required to adequately tamponade the retinal breaks.

The second injection is performed in exactly the same manner as the first, with the same approach regarding the anterior chamber paracentesis and the intravitreal gas injection. Again, a minimum of 0.6 cc of SF6 gas is injected.

It is important to prevent intravitreal gas from coming into the anterior chamber when performing the paracentesis.

In patients at risk for this, such as sulcus IOL from complicated cataract surgery, steps can be taken to minimize this risk, such as performing the tap with the head raised and with a small pupil.

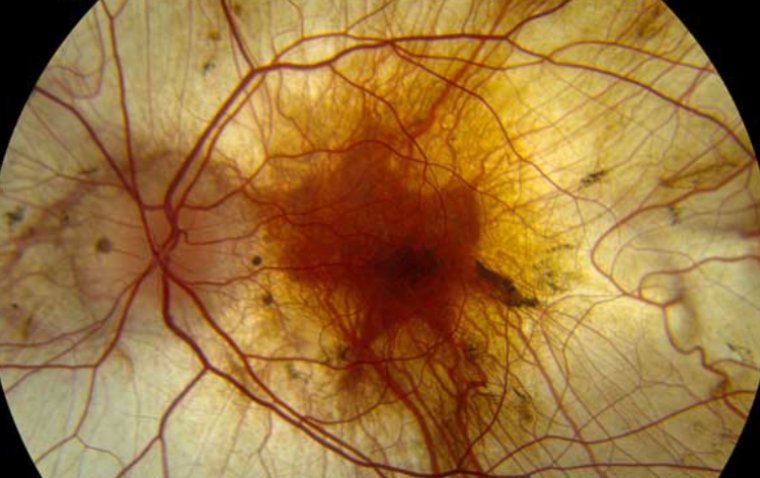

When a Pneumatic Retinopexy has Failed, Do Not Delay Surgery

Multiple randomized trials have shown that a pneumatic failure does not jeopardize future success. First of all, it is important to be absolutely certain that the pneumatic is truly failing from an open break.

In many cases there can be residual fluid that is not associated with an open break. Subsequent vitrectomy in these cases is slightly complicated because a retinotomy will need to be made to remove the fluid, often inferiorly.

It is important to assess if residual subretinal fluid after a PnR is getting better, staying the same or getting worse. If there is an open break, then the fluid should be worsening, and the patient should have surgery arranged.

Performing the surgery in a timely manner within a few days, will allow the patient to have an excellent outcome despite the pneumatic failure. Delaying surgery can result in proliferative vitreoretinopathy and poor anatomic and functional outcomes.

We always ask patients to remain face down while waiting for surgery. This allows the macula to remain attached and in phakic patients keeps the gas bubble away from the lens.

It is critical to tell the phakic patient to not lie supine, even in the preoperative area, and to be face down until they see you in the operating room.

The patient lying on their back even for an hour on the day of surgery can cause the view to be lost during a vitrectomy. In rescue scleral buckle cases, gas can be removed, but usually we work around it.

In most cases, we try not to drain subretinal fluid externally, as when the eye is rotated the gas bubble can come to the quadrant of drainage and push on the detached retina, leading to retinal incarceration or a retinal break.

Use Topical Steroids Following the Procedure and Subconjunctival Lidocaine for Laser Retinopexy

Laser retinopexy following PnR can be difficult for the patient, particularly in the early post-pneumatic period. Without topical steroids, the eye can be quite tender on day 1 or 2, making the laser even harder.

Topical steroids reduce the inflammation and allow the patient to tolerate the laser retinopexy and scleral depression better. If performing extensive laser retinopexy, especially temporally or nasally over the long ciliary nerve, a subconjunctival lidocaine injection can be very helpful.

Although there are a lot of nuances to performing PnR, these can be learned with experience. There is great satisfaction that can be achieved by reattaching the retina in your office, and allowing the patient to avoid surgery with better anatomic integrity and superior long-term functional outcomes.

Patients who have had successful PnR almost seem like treatment-naïve eyes when they come back for follow-up, whereas patients who have had scleral buckle or vitrectomy are almost never the same.

Patients following PnR are similar to patients who have had laser retinopexy for a retinal tear. Retinal detachment repair is continuously evolving with advances in multimodal imaging providing more and more information regarding the integrity of anatomic reattachment.

Current evidence supports the use of PnR for cases meeting clinical trial criteria, and every vitreoretinal surgeon should have sufficient experience with the procedure such that they are comfortable offering it to appropriate patients.

It is important to start with easier cases and to enjoy the process of learning the art of PnR.

(1).jpg)