Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus (HZO), commonly known as shingles, is a viral disease characterized by a unilateral painful skin rash in one or more dermatome distributions of the fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve), shared by the eye and ocular adnexa.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs when the varicella-zoster virus is reactivated in the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus represents up to one fourth of all cases of herpes zoster.

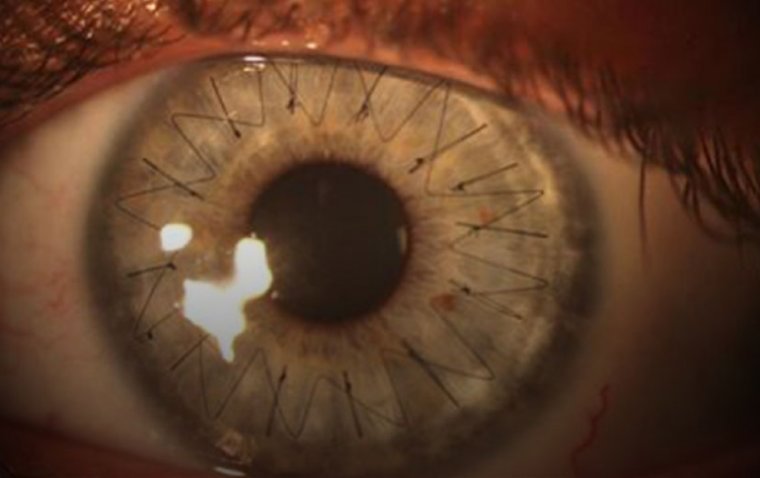

Most patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus present with a periorbital vesicular rash distributed according to the affected dermatome. A minority of patients may also develop conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, and ocular cranial-nerve palsies.

Permanent sequelae of ophthalmic zoster infection may include chronic ocular inflammation, loss of vision, and debilitating pain.

Antiviral medications such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir remain the mainstay of therapy and are most effective in preventing ocular involvement when begun within 72 hours after the onset of the rash.

Timely diagnosis and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus, with referral to an ophthalmologist when ophthalmic involvement is present, are critical in limiting visual morbidity.

Herpes zoster, also referred to as shingles, is a common infection most typically caused by the reactivation of varicella zoster virus that lies dormant (sometime for decades) in the dorsal root nerve ganglion following primary chickenpox infection.

In 10-20% of cases, the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) is involved and herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs.

A patient with herpes zoster ophthalmicus typically presents with a painful, unilateral, vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution.

It may (but not always) present with ocular involvement including painful inflammation of the anterior, and rarely, posterior structures of the eye including conjunctivitis, keratitis, iritis and uveitis. This is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed by viral swabs.

History

Whilst taking a patient history, it is key to ascertain when the rash started, initiating antiviral treatment within 72 hours from the onset of rash is essential in reducing the risk of long-term ocular complications including uveitis, stromal keratitis and pseudo-dendritis.

To decipher whether there is an ocular involvement it is pivotal that the following symptoms are enquired about: eye pain, diplopia, discharge, red eye, photophobia, visual loss / disturbance, floaters and flashing lights.

Systemic symptoms including general malaise, headache and fever should also be asked. It is then important to enquire about past medical history particularly if there is any recent systemic illness which would impair immunity thus increasing the risk of developing herpes zoster.

Additionally, asking whether there is any history of immunosuppression (including malignancy, HIV or history of chickenpox) would aid with investigations and starting stronger antiviral treatment. Likewise, asking if the patient is on any immunosuppressive medication would be beneficial.

Finally, taking a thorough social history is pivotal to ascertain if there are any vulnerable populations including children and pregnant women who the patient has recently been in close contact with that may require urgent medical attention if showing signs of varicella or herpes zoster.

Examination

On general examination, look at the pattern and distribution of the rash: a unilateral (not crossing the midline) vesicular rash along the V1 dermatomal distribution would highly indicate herpes zoster.

A key sign to be aware of is Hutchinson’s sign, this is a rash involving the tip, side or root of nose. It indicates involvement of the nasociliary branch of the trigeminal nerve and is strongly correlated with ocular inflammation and permanent corneal denervation.

Using fluorescein drops to determine if there are any corneal changes is also essential. Finally, signs of infection both locally (purulent discharge) and spread (e.g. confusion in encephalitis) need to be assessed.

On ocular examination the external eye should be examined for conjunctival redness, acuity should be assessed using Snellen chart and viral swabs taken for herpes simplex / varicella zoster if there is diagnostic uncertainty, e.g. if the rash is atypical.

After external examination of the eye, a dilated fundus examination can then be performed including intraocular pressures.

Management

The key in managing patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus regardless of ocular involvement is initiating antiviral treatment (oral aciclovir is first line) within 72 hours of the onset of rash. Ocular involvement occurs in approximately 50% of HZ patients without the use of antiviral therapy.

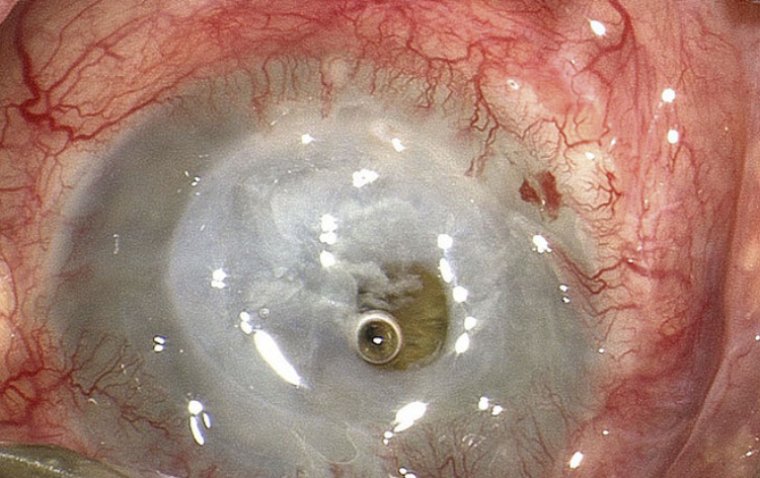

If there is any evidence of uveitis or stromal keratitis, topical steroids should be used. Immunosuppressive therapy should be used for scleritis. Topical anaesthesia should not be used as it prevents corneal healing and may worsen corneal denervation.

Analgesia and lubricating eye drops should also be considered. Educating patients regarding avoiding close contact until vesicles have fully crusted over with vulnerable populations, particularly children and pregnant women should also be reinforced by healthcare professionals.

Complication

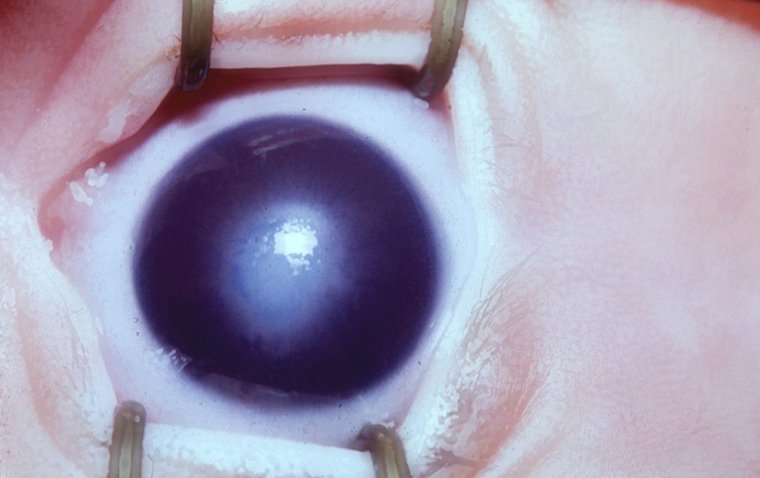

The two most important complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus are uveitis (pain and photophobia without discharge) and acute retinal necrosis (pain with loss of vision +/- floaters).

Other complications include: conjunctivitis, corneal pseudo-dendritis, episcleritis, post-herpetic neuralgia and disciform keratitis.

Prevention

The recombinant herpes zoster vaccine is recommended for adults ≥70 years in the UK and has been shown to reduce cases of herpes zoster by 38%.

Public health education campaigns would be useful to highlight the importance of this vaccination to this population given the severity of the complications that may arise from it if not identified or treated appropriately.

(1).jpg)