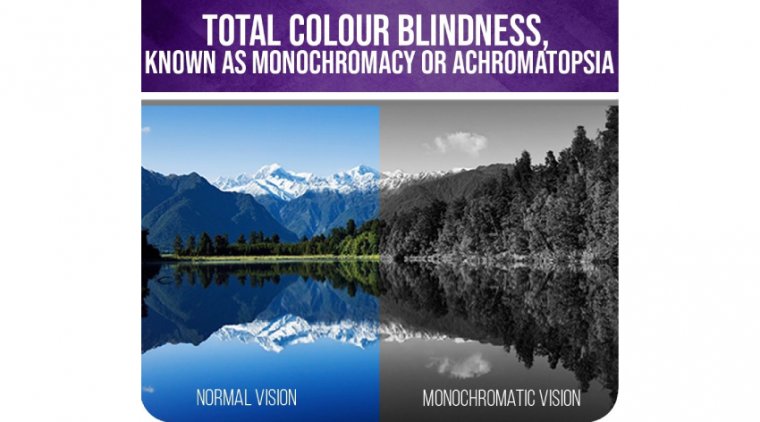

Dealing With Achromatopsia

Achromatopsia, also known as total color blindness, is a medical syndrome that exhibits symptoms relating to at least five conditions.

The term may refer to acquired conditions such as cerebral achromatopsia, but it typically refers to an autosomal recessive congenital color vision condition, the inability to perceive color and to obtain satisfactory visual acuity at high light levels, typically exterior daylight.

The syndrome is also present in an incomplete form which is more properly defined as dyschromatopsia. It is estimated to affect 1 in 30,000 live births worldwide.

Achromatopsia is a condition characterized by a partial or total absence of color vision. People with complete achromatopsia cannot perceive any colors; they see only black, white, and shades of gray. Incomplete achromatopsia is a milder form of the condition that allows some color discrimination.

The cause of this disorder is absence of functioning cones (photoreceptors) in the retina. Patients with complete achromatopsia are only able to perceive black, white and gray shades.

Their world consists of different shades of gray ranging from black to white, rather like only seeing the world as black and white. Patients with incomplete achromatopsia may perceive some limited colors.

Achromatopsia also involves other problems with vision, including an increased sensitivity to light and glare (photophobia), involuntary back-and-forth eye movements (nystagmus), and significantly reduced sharpness of vision (low visual acuity).

Affected individuals can also have farsightedness (hyperopia) or, less commonly, nearsightedness (myopia). These vision problems develop in the first few months of life.

Achromatopsia is different from the more common forms of color vision deficiency (also called color blindness), in which people can perceive color but have difficulty distinguishing between certain colors, such as red and green.

Achromatopsia is characterized by reduced visual acuity, pendular nystagmus, increased sensitivity to light (photophobia), a small central scotoma, eccentric fixation, and reduced or complete loss of color discrimination.

All individuals with achromatopsia (achromats) have impaired color discrimination along all three axes of color vision corresponding to the three cone classes: the protan or long-wavelength-sensitive cone axis (red), the deutan or middle-wavelength-sensitive cone axis (green), and the tritan or short-wavelength-sensitive cone axis (blue).

Most individuals have complete achromatopsia, with total lack of function of all three types of cones. Rarely, individuals have incomplete achromatopsia, in which one or more cone types may be partially functioning. The manifestations are similar to those of individuals with complete achromatopsia, but generally less severe.

Achromatopsia frequently results in hyperopia. The first few weeks after birth are when nystagmus initially appears, followed by an increase in light sensitivity. Best visual acuity varies with illness severity; in total achromatopsia, it is 20/200 or below, whereas in incomplete achromatopsia, it can reach 20/80.

Visual acuity is usually stable over time; both nystagmus and sensitivity to bright light may improve slightly.

Although the fundus is usually normal, macular changes (which may show early signs of progression) and vessel narrowing may be present in some affected individuals. Defects in the macula are visible on optical coherence tomography.

Achromatopsia is an autosomal recessive disease that affects approximately 1:30,000 individuals and is associated with complete loss of cone function.

It is most commonly caused by mutations in the CNGB3 and CNGA3 genes and is associated with severely reduced visual acuity and extreme photosensitivity, resulting in daytime blindness.

Due to a loss of cone cell function, patients have complete loss of color discrimination. Most patients with achromatopsia have an average visual acuity of 20/200, resulting in a diagnosis of legal blindness.

Profound sensitivity to light during the day results in significant impairment in visual function, and many patients cope by wearing darkly tinted glasses to lessen the effect of light sensitivity.

Even though this inherited retinal disease was the focus of a popular book by the well-known Dr. Sacks, a recent global survey conducted by Achroma Corp. shows that this disease remains relatively misunderstood and underdiagnosed, and individuals with achromatopsia face a long and difficult journey in pursuit of an early and accurate diagnosis.

DIVING DEEPER

In an effort to better understand and engage the achromatopsia community, the “Understanding the Achromatopsia Patient Experience” survey was conducted online in January 2018 on behalf of Achroma Corp. and in partnership with Applied Genetic Technologies Corp. (AGTC), a gene therapy company.

The survey, distributed through Achroma Corp.’s network, was completed by 226 respondents who have been diagnosed with—or have a child who has been diagnosed with—achromatopsia. Initial symptoms of achromatopsia typically appear in infancy, as this is a congenital disorder.

Symptoms can include nystagmus (rapid involuntary eye movements), as well as photosensitivity and markedly reduced visual acuity.

According to the global survey, photosensitivity is reported as being the most debilitating and bothersome symptom of achromatopsia; on a 0–100 scale, adults with achromatopsia give photosensitivity a rating of 77 on severity and 75 on being bothersome.

This severe photoaversion significantly and negatively impacts their ability to function daily and takes an emotional toll on their health and wellness. The majority of affected individuals reported that their photosensitivity had not changed over time (53% of adults and 82% of children).

However, more than one-third of adults believed that their photosensitivity had worsened over time. These individuals reported that they had taken additional steps to adapt and function.

Primarily, 58% of individuals adapted by using eyewear with a darker tint or extreme gradient, 53% expanded their use of eyewear and 44% avoided the outdoors.

Regarding diagnosis, most patients in the survey described a long and circuitous route to correct diagnosis, with a relatively longer course to diagnosis for adults as compared to the children.

Parents typically pursue answers from their general or pediatric healthcare providers, and see an average of four healthcare providers in a span of three years before receiving a diagnosis for their child, with 68% taking more than a year to receive a diagnosis after the initial onset of symptoms.

Twenty-three percent of children still received an incorrect diagnosis of retinal or cone dystrophy before being accurately diagnosed with achromatopsia. Adults with achromatopsia usually see an average of seven healthcare providers over a span of more than five years to receive the correct diagnosis.

More than onethird of these individuals were misdiagnosed with retinal or cone dystrophy before receiving the correct diagnosis of achromatopsia.

The survey results indicate that only 58% of adults and 65% of children with achromatopsia have received genetic testing to confirm the correct diagnosis and the underlying gene responsible.

In the past, the lack of genetic confirmation of disease could be blamed on the lack of therapeutic options.

Due to this, many ophthalmologists and their achromatopsia patients resigned themselves to simply managing the disease and never sought out genetic testing to secure or confirm a correct diagnosis.

For the 40% of adults who had not received genetic testing, the most commonly cited reasons for not seeking genetic testing were the following: > Perceived cost (34%) > Lack of information about how to access genetic testing (31%) > Lack of information about the availability of genetic testing (29%)

For parents of children with achromatopsia who had not received genetic testing, the most commonly cited reason was lack of information about accessing genetic testing (27%). However, even in the past few years, the landscape for achromatopsia has radically changed.

With several gene therapy studies in achromatopsia under way, it becomes imperative that ophthalmologists have a conversation with their inherited retinal disease patients about receiving genetic testing.

Currently, members of the Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) registry who reside in the United States and have a clinical diagnosis of an orphan inherited retinal dystrophy studied by the foundation can participate in a free genetic testing and ocular genetic counseling study with the assistance of their eye care professional.

This research study, which is IRB-approved and available for a finite time, is available through the FFB registry (www.myretinatracker.org).

By knowing their specific gene mutation, achromatopsia patients, as well as others living with inherited retinal diseases, may have the opportunity to participate in applicable clinical trials.

These clinical trials are investigating potential treatments for the condition while also advancing the scientific understanding of achromatopsia.

AGTC is currently recruiting for two phase I/II clinical trials for individuals with achromatopsia caused by mutations in either the CNGB3 or the CNGA3 gene.

(1).jpg)