Ophthalmology research in 2025 was defined by significant progress in regenerative medicine, drug de...

read moreThe ophthalmology industry in 2025 continued to evolve through strategic acquisitions and partnershi...

read moreThe AI in ophthalmology sector is evolving rapidly, introducing Artificial Intelligence tools in oph...

read moreThe year 2024 has been a remarkable period for advancements in ophthalmology, with groundbreaking in...

read moreThe year 2024 has been a pivotal one for ophthalmology, with several novel FDA approvals introducing...

read more2024 has been a landmark year for breakthroughs in ophthalmology research, showcasing transformative...

read moreIn 2024, the ophthalmic industry experienced a transformative year driven by strategic company acqui...

read moreA new analysis published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology reveals that nearly one in three ch...

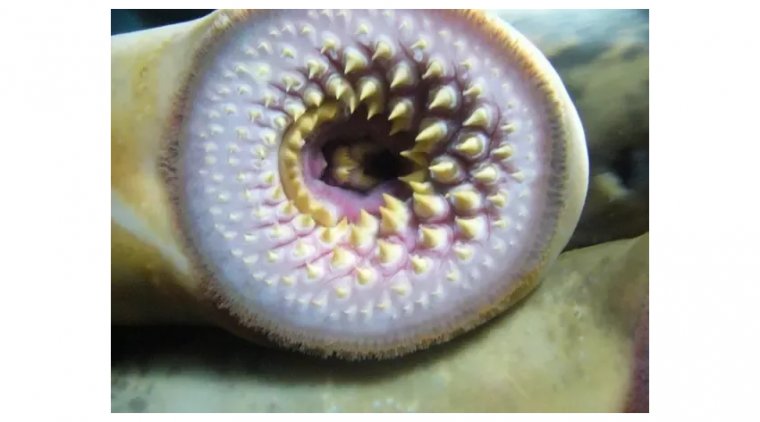

read moreLamprey Eye Disease, also known as "Lamprey Disease," is a hoax that has been circulating on the int...

read moreA recent study highlights the potential of ChatGPT-4.0 in accurately answering questions related to ...

read more More

More