Understanding Retinopathy of Prematurity: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments

Retinopathy of Prematurity is one of the critical challenges in neonatal care, especially for premature babies born before 31 weeks of gestation and known as grams weighing less than 1,500. This disease, expressing itself as impaired or even complete abnormalities in the blood vessels running through the retina, may eventually cause not only loss of sight but also blindness. This post covers a wide area of ROP, including its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, management and treatment to keep sight-threatening complications in this group of infants away.

Introduction to Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP)

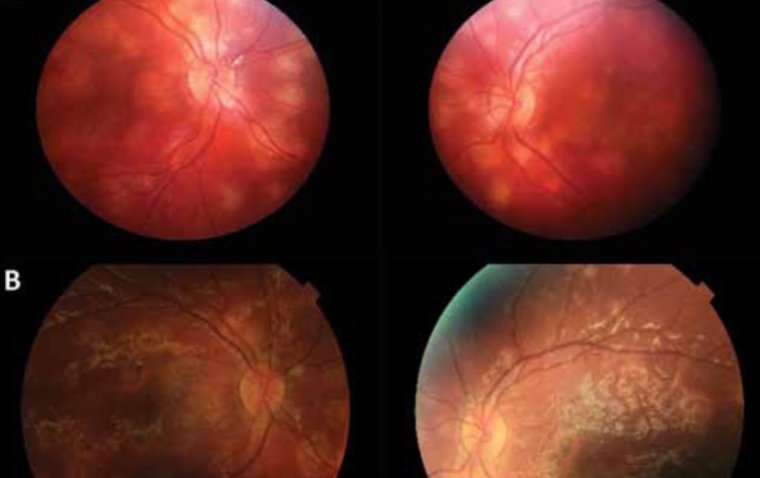

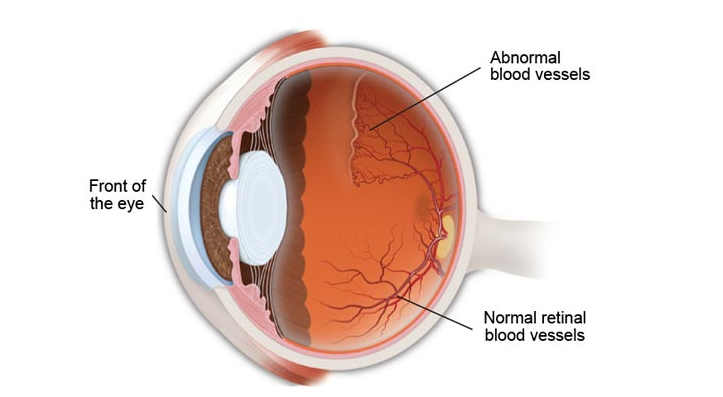

ROP (Retinopathy of Prematurity) is a complex condition of the retinal segment of premature fetuses. During the fetal stage, blood vessels in the retina emerge from the optic nerve into the peripheral retina and terminate there. However, due to early termination of pregnancy, as in premature babies, the vascularization of the retina is interrupted, resulting in the retina not being able to receive a complete report. Therefore, the abnormal blood vessels will change shape and eventually cause retinal detachment and vision loss if not adequately treated.

Causes and Risk Factors of Retinopathy of Prematurity

The development of ROP is influenced by multiple factors, particularly those related to the premature birth and the subsequent care of the infant. Understanding these causes is crucial for preventing and managing the condition effectively.

1. Prematurity and Retinal Development

The primary cause of ROP is the premature birth of an infant, which interrupts the normal vascular development of the retina:

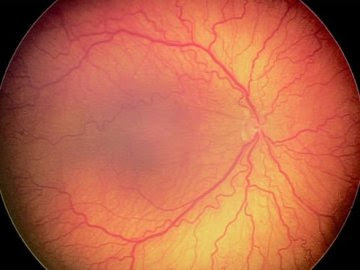

● Incomplete Vascularization: In a developing fetus, the retina's blood vessels begin to form at around 16 weeks of gestation and are not fully developed until about the time of normal birth (around 40 weeks). Infants born prematurely have an underdeveloped retinal vascular system that needs to continue growing after birth.

● Abnormal Vascular Proliferation: Due to premature birth, the retina's normal vascular growth may pause and then restart abnormally, leading to the proliferation of abnormal vessels. These vessels are fragile and prone to leaking and bleeding, which can cause scarring and potentially lead to retinal detachment.

2. Role of Oxygen

Oxygen plays a dual role in the development and progression of ROP, making it one of the most critical external factors:

● Oxygen Supplementation: Premature infants often require supplemental oxygen because their lungs are not fully developed. However, high levels of oxygen can halt the normal growth of blood vessels in the retina and cause existing vessels to degenerate.

● Fluctuating Oxygen Levels: It is not just high levels of oxygen that can cause ROP; significant fluctuations in oxygen levels can also stimulate abnormal vessel growth. After high oxygen exposure, when an infant is returned to lower levels, there can be a compensatory burst in vascular growth factor production, leading to rapid abnormal vessel growth.

3. Other Contributing Factors

Several other factors can influence the development and severity of ROP:

● Growth Factors: The production of certain growth factors, such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), is crucial in normal retinal development and in the pathology of ROP. Imbalances in these factors can lead to the proliferation of the abnormal vessels seen in ROP.

● General Health and Nutrition: The overall health of the infant can impact ROP development. Infants who are sicker or have poor nutrition may have more severe ROP. Nutritional factors, particularly the levels of certain fats and proteins, can influence retinal health and vascular development.

● Exposure to Light: There has been some research suggesting that excessive light exposure might exacerbate ROP, although this is less clearly established and somewhat controversial compared to the role of oxygen.

● Blood Transfusions: Some studies have linked blood transfusions in premature infants to an increased risk of ROP, possibly due to fluctuations in blood oxygen-carrying capacity and changes in blood flow.

● Inflammation: Systemic infections and local inflammatory processes can influence the development of ROP. Inflammatory cytokines can increase the production of growth factors like VEGF, further promoting abnormal vascular growth.

4. Genetic Susceptibility

While the environment of the premature infant plays a significant role in the development of ROP, genetic factors also contribute to an infant's susceptibility to the condition:

● Genetic Predisposition: Research indicates that certain genetic markers may make some infants more prone to develop ROP. These genetic differences can affect how infants respond to oxygen and other risk factors.

● Family History: A family history of ROP, particularly in siblings who were also premature, can indicate an increased risk, suggesting a possible genetic component to the disease.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Retinopathy of Prematurity

ROP has variable clinical presentation depending on the disease’s severity. Early ROP may be asymptomatic, and the only way to identify it is through routine ophthalmologic examination. Here are the common symptoms:

● Poor Visual Tracking or Fixation: Infants with ROP often have trouble following objects with their eyes. Normally, babies start to track moving objects with their eyes at around 2 to 3 months of age. However, those with significant ROP may show delayed development of this skill or might not be able to do it consistently.

● Abnormal Eye Movements: Known as nystagmus, this symptom involves involuntary and repetitive movements of the eyes. These can appear as shaking or oscillating eyes and often indicate that the infant has some visual impairment.

● Strabismus: This condition involves misalignment of the eyes, commonly referred to as crossed eyes or wall eyes. Strabismus occurs when the muscles controlling the movement of the eye are not coordinated, which can be a direct result of vision problems from ROP.

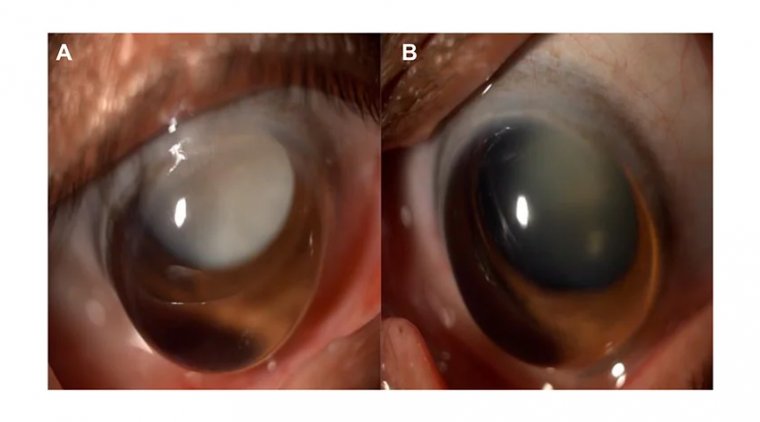

● White Pupils (Leukocoria): In some cases of severe ROP, the pupil may appear white when light is shone into the eye, similar to the reflection seen in a cat's eye in low light. This can indicate that there is something abnormal reflecting light inside the eye, such as a retinal detachment or scar tissue.

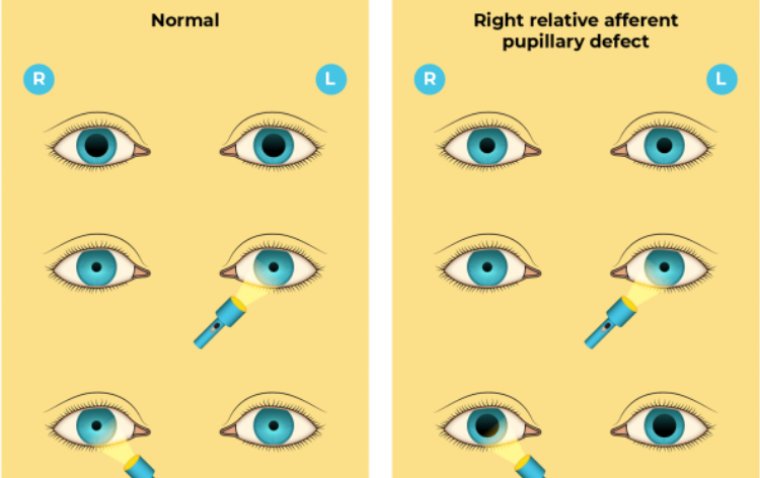

● Poor Pupil Response: The pupils of infants with severe ROP may not constrict or respond to light as expected. This lack of response can be due to abnormal development of the retina and the neural pathways that control pupil dilation and constriction.

● Severe Myopia (Near-sightedness): Premature infants with ROP often develop myopia. This is because the shape of the eye can be altered by the abnormal growth of retinal blood vessels and scar tissue, changing the refractive properties of the eye.

● Visual Impairment: As ROP progresses, especially without treatment, it can lead to varying degrees of visual impairment. In milder cases, this might be slight blurring, but in severe cases, it can lead to complete blindness.

● Gaze Preference: Infants with ROP might show a preference for looking in certain directions. This could be due to areas of the retina that are less affected by the disease, allowing better vision in specific fields of view.

With the disease’s progression, affected infants can present without redness, excessive tearing, and abnormal eye movements . When not treated on time, the disease can progress to severe forms culminating to retinal detachment and permanent vision loss.

Diagnosis and Screening for Retinopathy of Prematurity

Early diagnosis of ROP is vital for appropriate therapy as well as a successful visual prognosis. The majority of high-risk premature infants undergo screening within the first few weeks of life and the frequency of subsequent examinations is determined by the severity of ROP and the infants’ stage of gestation. The pupils are dilated during the test, and the retina is checked through indirect ophthalmoscopy or digital retinal photography. The disease’s grading is based on the International Classification of Retinopathy Prematurity definitions, which is essential for decision-making regarding the required form of treatment.

Management and Treatment Options for Retinopathy of Prematurity

The treatment of ROP mostly includes several healthcare professionals, such as neonatologists, ophthalmologists, and pediatricians. If the cases are less severe, it is possible that they will resolve entirely on their own. However, in severe situations, intervention and treatment will prevent the complication and help avoid vision loss. Among common treatments are:

1. Laser Therapy

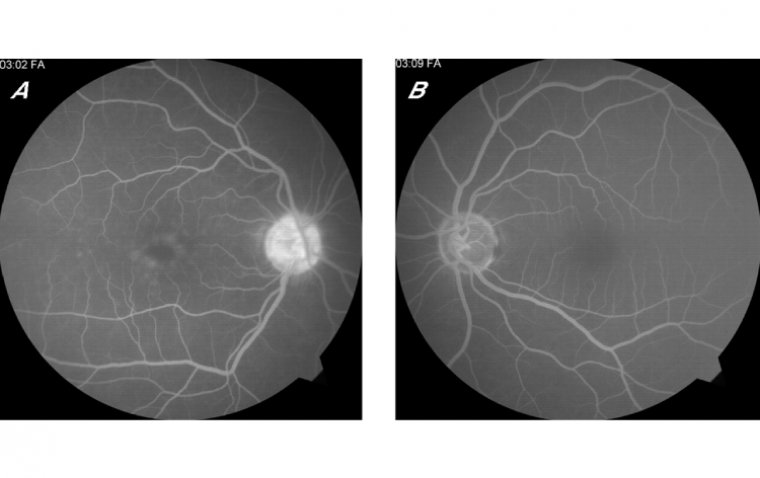

● Peripheral Retinal Ablation: This is the conventional treatment for severe ROP, particularly for stage 3 and some stage 2 cases. The procedure involves using laser energy to ablate the peripheral avascular retina, which is the area of the retina without normal blood vessels. By doing this, production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which drives abnormal blood vessel growth, is reduced, thereby preventing progression to retinal detachment.

2. Cryotherapy

● Freezing the Peripheral Retina: Similar to laser therapy, cryotherapy involves freezing the avascular areas of the retina. This treatment is less commonly used today but can be an option when laser therapy is not available or feasible. It works on the same principle as laser therapy, aiming to reduce VEGF production.

3. Anti-VEGF Medications

● Intravitreal Injections: In certain cases, especially for zone I ROP (the central retina) or posterior zone II disease, anti-VEGF drugs such as bevacizumab (Avastin) or ranibizumab (Lucentis) may be used. These medications are injected directly into the eye and work by inhibiting the activity of VEGF, thereby reducing the growth of abnormal blood vessels.

Benefits and Risks: Anti-VEGF treatments can be particularly useful for aggressive posterior ROP because they can reduce the need for more invasive surgeries. However, the long-term systemic effects of these medications in infants are still under study, and careful consideration is required before proceeding.

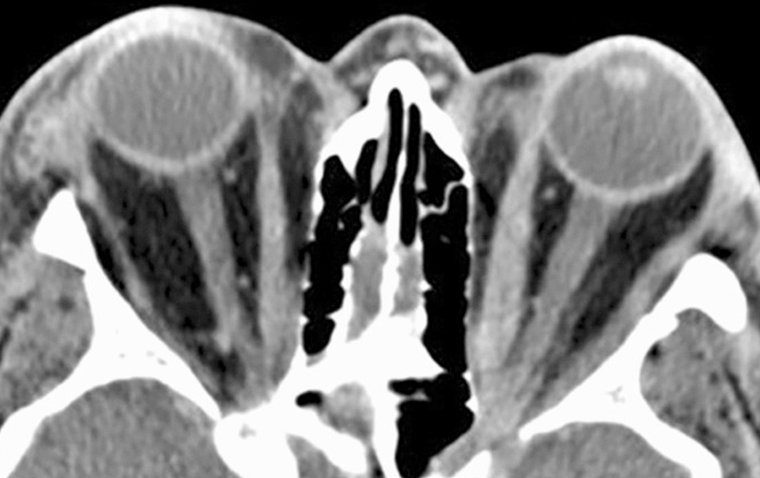

4. Vitrectomy

● Surgical Intervention: For advanced ROP, particularly in cases of stage 4 (partial retinal detachment) or stage 5 (total retinal detachment), a vitrectomy might be necessary. During this procedure, the vitreous gel that is pulling on the retina is removed, and scar tissue is carefully peeled away. This can sometimes prevent or minimize retinal detachment.

● Scleral Buckling: Another surgical option for advanced ROP is scleral buckling. This involves placing a flexible band around the eye to counteract the force pulling the retina out of place.

5. Supportive Care

● Monitoring Development and Vision: Infants with ROP, especially those who have undergone treatment, need long-term follow-up to monitor their visual development and to manage any complications, such as myopia and strabismus.

● Use of Corrective Eyewear: Many children who have had ROP will require glasses, particularly if they develop high myopia.

● Low Vision Aids and Therapy: For children who have significant visual impairment, tools like magnifiers and other low vision aids can be beneficial, along with orientation and mobility training.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

The prognosis for infants with ROP depends on the severity of the disease and the timeliness of intervention. With early detection and appropriate treatment, many infants with ROP can achieve favorable visual outcomes and lead relatively normal lives. However, severe cases of ROP may result in permanent vision loss or blindness, underscoring the importance of early screening and intervention.

Conclusion

Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) remains a significant challenge in neonatal care, particularly for premature infants. By understanding the causes, symptoms, and management strategies for ROP, healthcare providers can implement timely interventions to prevent vision loss and improve long-term outcomes for affected infants. Through ongoing research and advancements in medical technology, the outlook for infants with ROP continues to improve, offering hope for a brighter future for these vulnerable individuals.

(1).jpg)