How to Diagnose Papilledema, A Swollen Optic Nerve?

Papilledema is the swelling of the optic nerve as it enters the back of the eye due to raised intracranial pressure. Fluid surrounding the brain is constantly produced and reabsorbed, maintaining just enough intracranial pressure to help protect the brain if there is blunt head trauma.

The differential diagnosis of swollen optic nerves differs according to whether the swelling is unilateral or bilateral, or whether visual function is normal or affected. Patients with a unilaterally swollen optic nerve and normal visual function most likely have optic nerve head drusen.

Patients with abnormal visual function most likely have demyelinating optic neuritis or non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy.

Patients with bilaterally swollen optic nerve heads and normal visual function most likely have papilloedema, and require neuroimaging followed by lumbar puncture.

However, if their visual function is affected, the most likely causes are bilateral demyelinating optic neuritis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein optic neuritis: these patients require investigating with contrast-enhanced MRI of the orbits.

Optic nerve swelling or edema can be an intimidating finding in the primary eyecare clinic. The diagnosis of a swollen optic nerve is based on clinical diagnosis, but the importance of a comprehensive case history cannot be overstated.

Ocular History

During the history, many important questions should be asked to help determine the etiology of the optic nerve edema. The clinician should begin by questioning if the condition is a one or two eyeball problem.

Bilateral optic nerve edema is a medical emergency. The onset and severity of vision loss and symptoms are important clues to consider. Rapid onset is characteristic of ischemic optic neuropathy, inflammatory and traumatic causes, and optic neuritis.

A gradual onset over time is typical of compressive, hereditary, toxic, and nutritional causes. Another important symptom: pain associated with eye movements. If present, it is hallmark differential for optic neuritis.

Systemic History

A detailed history of systemic health is important. Diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and a history for being treated for or having malignancy or autoimmune disease is critical to understand potential risks associated with optic nerve edema.

Current and previous medications can be clues because many can be directly or indirectly toxic to the optic nerve. These drugs include tetracycline, cyclosporine, methotrexate, ethambutol, amiodarone, alcohol, and tobacco, to name a few.

Finally, reviewing the patient’s general health, including weight, eating habits, and social activities such as drinking, smoking, and illegal drugs will help provide an overall health picture, knowing that toxic and nutritional causes are in the differential diagnosis paradigm.

Clinical Exam

The clinical eye exam is the second step of process. With any optic nerve disease, ODs should pay close attention to several exam elements.

Important exam elements include: – Subjective and objective visual acuity – Pupils – Extra-ocular muscles – Color vision – Contrast sensitivity – Visual field testing – Anterior and posterior chamber observation – Optic nerve observation

Visual acuity can be normal or impaired, and subjectively a patient may complain of blurry letters or shadows around letters and an overall decrease in clarity.

Pupil testing is extremely important in assessing optic nerve disease. A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) can be detected performing the swinging penlight pupil test conducted in a dark room to assess full amplitude of pupillary response.

Color vision and color desaturation testing can be performed with Ishihara color plates and red-capped bottle. Dyschromatopsia, or the ability to perceive colors as abnormal, is a sensitive indicator of optic nerve disease.

During the dilated fundus exam, the clinician should look for evidence of cells in the anterior chamber and vitreous.

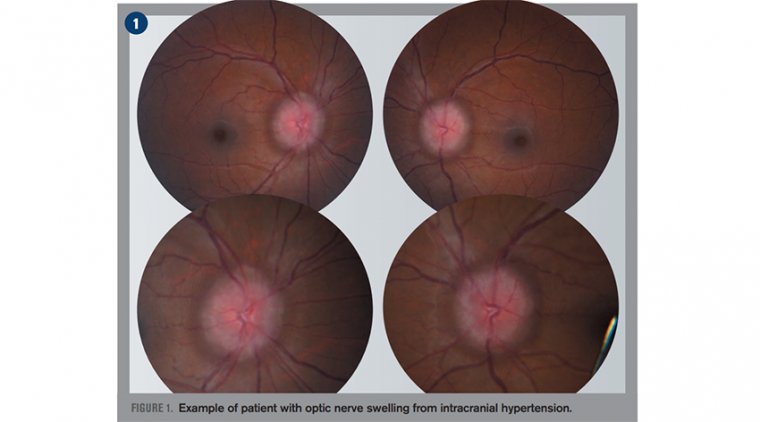

This would indicate that the disc swelling is secondary to a uveitic process. When assessing the optic nerve, stereoscopic views of the disc provide the quality and detail needed to determine disc edema from elevation.

The optic nerve will appear elevated and hyperemic with blurred margins obscuring peripapillary vessels as they leave the disc. It is important to assess the spontaneous venous pulsation (20 percent of normal population)—it will not be seen if swelling is present.

Another clinical sign to look for is buckling or retinal folds of the temporal aspect of the disc, also known as Paton’s lines.

If optic nerve edema is suspected, the standard method of grading disc edema by ophthalmoscopy is the Modified Frisén Scale.

It is an ordinal scale with subjective evaluation and grades ranging from 0 (no edema) to 5 (severe degree of edema) with characteristic findings for each grade.

Additional testing crucial to accurately diagnosing optic nerve swelling are visual field (VF) testing and optical coherence tomography (OCT).

VF testing can be confrontation, kinetic (Goldmann), or automated static perimetry (Humphrey).

VF defects take several patterns: central, arcuate, altitudinal, and generalized. Specific patterns can help the clinician correlate to specific diagnoses.

OCT uses light to provide images to the micron level and is an objective, noninvasive alternative to analyze the optic nerve head and quantify the status of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL).

Elevation of the RNFL is compared to age-related normative values to help confirm the already visualized ophthalmoscopy Frisén Scale findings.

Bilateral optic nerve swellling Papilledema is acquired bilateral optic nerve swelling due to increased intracranial pressure secondary to increased cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), which has specific etiologic implications.

Papilledema is a true ocular emergency because it can occur from structural space occupying lesions such as large tumors, hydrocephalus, vascular abnormalities, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and arteriovenous fistulae.

Due to these pathologies, it is imperative to begin the process of neuroimaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast of the brain, orbit, and optic nerve, and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) of the brain.

A referral to neuroophthalmology is warranted to evaluate and manage findings from the results of neuroimaging. If neuroimaging is negative, it is important to follow up with lumbar puncture to measure opening pressure and biochemistry, microbiology, and cytology of the CSF.

Note papilledema in the pediatric population may include but not limited to Guillain-Barre syndrome, spina bifida, hydrocephalus, trauma/subdural hemorrhage, and meningitis.

After exclusion of potentially life-threatening conditions and a normal CSF, determine if the opening pressure on lumbar puncture is elevated (>20 cm H2 0). It is also important to note that the modified Dandy criteria are still not met.

This diagnostic criteria mandate identifying other potential causes is necessary—idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a diagnosis of exclusion once all other potential causes have been ruled out.

The most common presenting symptoms are headache, occurring in more than 90 percent of patients, as well as pulsatile tinnitus, photopsia, and retrobulbar pain.

First-line treatment for IIH should concentrate on weight loss and management with a neuro ophthalmologist to lower CSF with an oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitor such as acetazolamide combined with a lowsodium diet as described in the IIHTT.

In patients with sudden and severe papilledema who may be at risk for irreversible vision loss, surgical intervention such as optic nerve sheath fenestration and cerebrospinal fluid shunting may be urgently needed.

It is key to rule out pseudo papilledema, a benign elevation of the optic nerve head with an underlying anomalous condition. These anomalies include optic nerve head drusen (ONHD), congenital crowded discs, and malinserted discs.

ONHD is the most common cause, accounting for 75 percent of clinically diagnostic disc anomalies. The scleral canal and optic disc of eyes with drusen are much smaller than average, thus showing elevated appearance.

OCT can aid in differentiating disc drusen from edema. Disc edema has a smooth internal disc contour and demonstrates a V-shaped hypo reflective space between sensory retina and RPE compared to the lumpy appearance found with disc drusen.

Congenital crowded discs are the result of a normal number of retinal axons passing through a small posterior scleral foramen with the resulting appearance of a densely packed optic nerve head as axons exit the globe.

A malinserted disc is due to oblique insertion of the nerve to the globe; primarily the nasal portion is elevated with the temporal portion depressed, giving it a swollen-like appearance.

Unilateral optic nerve swelling Unilateral optic nerve swelling can be caused by different pathogenic processes, including demyelinating, vascular, compressive, inflammatory, infectious, infiltrative, toxic, nutritional, and hereditary causes.

Demyelinating or optic neuritis (ON): History of sudden vision loss in one eye and pain associated with eye movement, prior history of neurological symptoms such as paresthesia, limb weakness, ataxia, chronic arm paresthesia, and diminution of vision following a rise in body temperature such as after exercise or a hot shower (Uhthoff’s phenomenon) is very common.

ON improves in 90 percent of cases over several weeks to near normal acuity. A brain MRI is needed to identify the presence of white matter lesions to confirm diagnosis.

Arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (AION): The presence of preceding transient visual loss, diplopia, temporal pain, jaw claudication, fatigue, weight loss, and myalgias is strongly suggestive of AION due to giant cell arteritis (GCA).

GCA causes only 6 percent of ischemic optic neuropathy, but it is visually devastating—a quick diagnosis can initiate treatment and prevent vison loss in the lateral eye. Other causes include polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and connective tissues disorders.

Non-arteritic AION is usually less severe and the most common cause of unilateral optic nerve edema in those >50 years. Usually associated with poor blood circulation to the optic nerve and associated with diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, hypercholesterolemia, and history of drug use.

Compressive: Lesions of the orbit and, less commonly, the optic canal can lead to optic nerve damage, and the visual loss is usually gradual and progressive. Common causes include optic glioma, meningioma, lympangiomas, pituitary adenomas, craniophyrangiomas, and Grave’s orbitopathy.

MRI and CT of brain and orbit are crucial for diagnosis. Inflammatory: A variety of systemic auto-immune disorders can cause optic nerve swelling. These include sarcoidosis, Bechet’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and syphilis.

Laboratory for each diagnosis should be included in the workup on these patients. Infiltrative: The optic nerve can be infiltrated by secondary tumors and malignancies, including metastasis, carcinomas, leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

Patients with a history of cancer and acquired optic nerve edema should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise. Neuroimaging should be ordered to help determine the correct diagnosis.

Infectious: Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can lead to optic nerve disease and edema. The most common causes are toxoplasmosis, Bartonella (Cat-scratch disease) and Lyme disease. Laboratory testing and good case history is important in isolating the causative pathogen.

Nutritious/toxic: Various drugs, toxins, and nutritional deficiencies can lead to optic nerve disease. These typically mimic and cause a secondary IIH.

These include tetracyclines, Vitamin A, amiodarone, and lithium.

Hereditary: The hereditary optic neuropathy that causes discs to appear swollen is Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and typically occurs between ages of 15 and 35.

Genetic testing and counseling should be considered if this is the suspected cause of optic neuropathy.

(1).jpg)