Granular Corneal Dystrophy: Exploring a Genetic Condition Affecting the Cornea

What Is Granular Corneal Dystrophy?

Granular corneal dystrophy (GCD) is an inherited eye disorder that affects the cornea, the clear front surface of the eye. This autosomal dominant condition is caused by mutations in the TGFBI gene, responsible for encoding a protein found throughout the body, including the cornea.

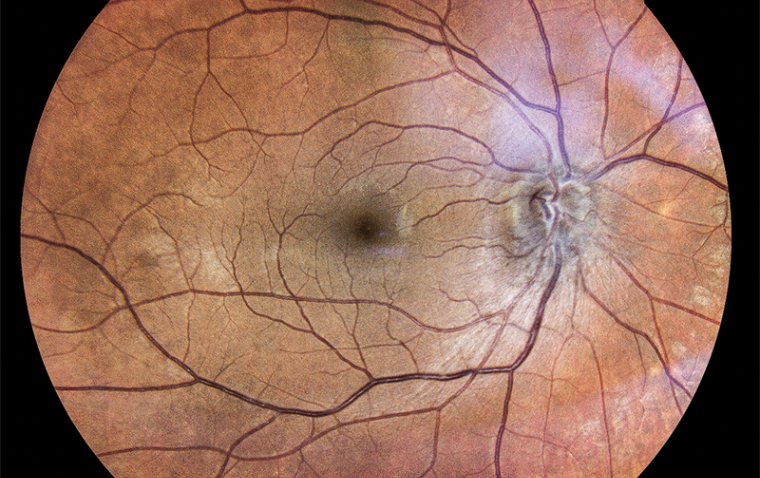

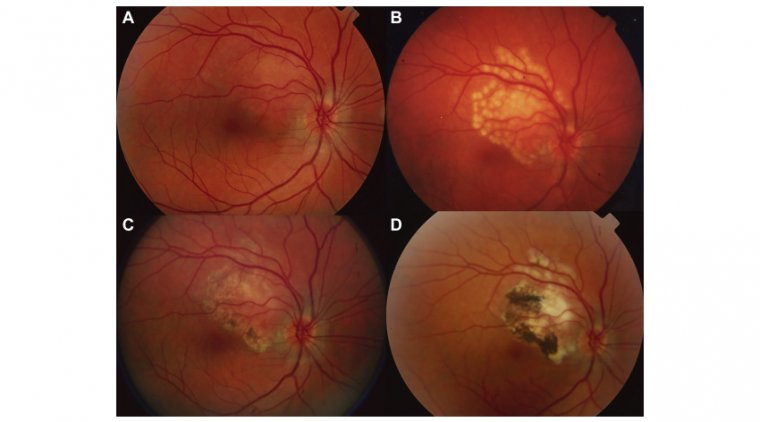

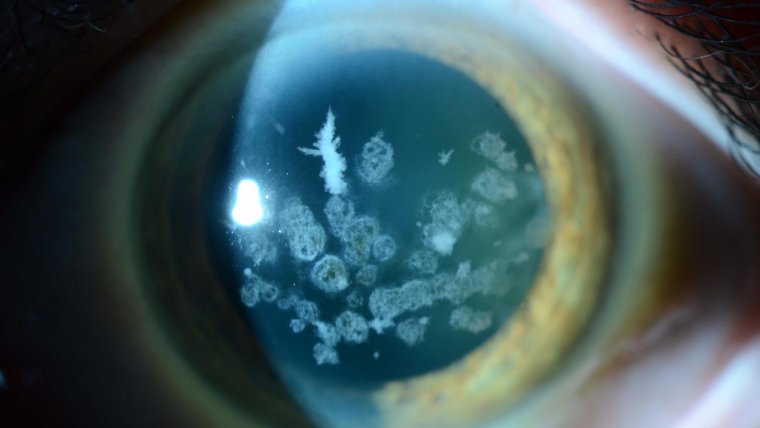

Characterized by the deposition of granular, amyloid, or mixed type opacities within the corneal stroma, GCD gradually impacts vision. The hallmark feature of this dystrophy is the presence of crumb-like granular deposits scattered throughout the cornea, primarily in the anterior stroma.

In GCD, the granular deposits usually start to appear during childhood or adolescence, gradually expanding and increasing in number over time. The resultant vision impairment is progressive, ranging from mild vision difficulties to severe loss of visual acuity.

Key Characteristics of GCD

● Opacities usually begin appearing in the first or second decade of life.

● Slow progression of vision impairment.

● Deposition of granules primarily in the corneal stroma.

● Granules appear as white or grayish breadcrumb-like deposits.

● Autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

The clinical manifestations of GCD are as diverse as the pebbles on a beach, warranting an individualistic approach to management. As we delve further into this genetic quirk of the cornea, let's remind ourselves that in ophthalmology, as in life, it's not just about seeing the granules, but understanding the beach they rest on.

.jpg)

Types and Genetics of Granular Corneal Dystrophy

The granular corneal dystrophy terrain is not monolithic but rather is characterized by a genetic variety, particularly noticeable in the types of this condition, mainly Granular Corneal Dystrophy Type 1 (GCD1) and Type 2 (GCD2).

GCD1, also known as classic granular corneal dystrophy or Groenouw type I, is characterized by the deposition of distinct granular opacities within the corneal stroma. These opacities are typically bread-crumb or snowflake-like in appearance and usually become visible within the first or second decade of life. The vision impairment in GCD1 is typically slow to progress, and severe vision loss is relatively rare.

GCD2, also known as Avellino corneal dystrophy, presents a different story. This condition, named after the Italian region where it was first described, is characterized by the mixed presence of granular and lattice (amyloid) deposits. This results in a more variable and usually more severe clinical presentation than GCD1.

In terms of genetics, both GCD1 and GCD2 are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. These forms result from mutations in the TGFBI gene, which plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of the cornea.

Differences between GCD1 and GCD2

● Appearance of Deposits: GCD1 presents with breadcrumb-like granular deposits, whereas GCD2 shows a combination of granular and amyloid deposits.

● Severity: GCD2 often leads to more severe vision impairment than GCD1 due to the additional amyloid deposits.

● Genetics: Both conditions result from mutations in the TGFBI gene and are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

Symptoms of Granular Corneal Dystrophy

The signs and symptoms associated with Granular Corneal Dystrophy can be as diverse as the corneal deposits they stem from. As with any dystrophy, the clinical presentation tends to vary from person to person, yet certain commonalities frequently observed can serve as effective signposts for diagnosis.

Generally, individuals with GCD start experiencing symptoms during childhood or adolescence, although the onset and progression may vary significantly among affected individuals. Some may notice symptoms only in middle age or later.

Here are the common symptoms often reported:

1. Blurry vision: This is often the first sign of GCD, manifesting as a gradual decline in visual acuity. The severity of vision impairment can range from mild to significant, depending on the number, location, and type of corneal deposits.

2. Photophobia: Light sensitivity is a frequent complaint among individuals with GCD, particularly in those with a severe form of the condition.

3. Presence of corneal deposits: These appear as grayish or whitish granules within the cornea, often resembling bread crumbs or snowflakes. These granules may increase in number and size over time, contributing to the progressive nature of vision impairment.

4. Foreign body sensation: Some patients may experience discomfort in the eyes, often described as a feeling of something stuck in the eye.

5. Recurrent corneal erosions: This involves the breakdown of the cornea's outermost layer, leading to severe pain, redness, and sensitivity to light.

How to Diagnose Granular Corneal Dystrophy

Diagnosing Granular Corneal Dystrophy is akin to piecing together a puzzle, relying on a combination of clinical observation, comprehensive eye examination, and imaging techniques. Often, the presence of characteristic corneal deposits and a positive family history can strongly hint at a diagnosis of GCD. However, to confirm the diagnosis and map the extent of corneal involvement, more precise measures are required.

The diagnostic journey typically involves:

● Comprehensive Eye Examination: This is the first step, where an ophthalmologist performs a detailed evaluation of the patient's eyes and vision. Slit-lamp examination can reveal the presence of characteristic granular deposits in the cornea.

● Corneal Topography: This imaging technique creates a detailed map of the cornea's surface curvature, assisting in visualizing any abnormalities indicative of GCD.

● Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT can provide high-resolution, cross-sectional images of the cornea, allowing precise identification of the location and extent of corneal deposits.

● Confocal Microscopy: This tool can capture detailed images of the cornea at a cellular level, further aiding in the identification of granular deposits.

● Genetic Testing: Since GCD is a genetic disorder, genetic testing can provide definitive proof of the condition by identifying mutations in the TGFBI gene.

Treatment Options for Granular Corneal Dystrophy

Once we've navigated the complex maze of diagnosing Granular Corneal Dystrophy, the focus then shifts to charting the best course of treatment. It's essential to bear in mind that the management approach is like fitting the right eyeglasses - it should be tailored to each patient's specific needs and condition severity.

Regular Monitoring and Lifestyle Modifications

In mild cases, regular monitoring might suffice, with the emphasis placed on addressing any potential discomfort or visual impairment with glasses or contact lenses. Ophthalmologists may recommend lifestyle changes, such as using sunglasses in bright light to decrease photophobia or using lubricating eye drops to help alleviate any foreign body sensation.

Corneal Transplantation

In more severe cases, when vision is significantly affected or when complications like recurrent corneal erosions arise, more invasive interventions may be necessary. Corneal transplantation, or keratoplasty, is often the procedure of choice.

There are two main types of corneal transplantation:

1. Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK): This full-thickness corneal transplant involves the surgical removal of the entire cornea, which is then replaced with a donor cornea.

2. Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty (DALK): A less invasive procedure where only the diseased layers of the cornea are removed and replaced with healthy donor tissue, preserving the innermost endothelial layer.

Risks, Benefits, and Long-Term Outcomes

Both types of corneal transplantation have proven effective in restoring vision in GCD patients. However, as with any surgical procedure, they come with potential risks, including infection, rejection of the donor cornea, and complications related to surgery.

In the long term, even though corneal transplantation can markedly improve visual acuity, there's a possibility of recurrence as the dystrophic deposits may accumulate in the donor cornea over time. Regular follow-up visits and vigilant monitoring of the condition are therefore crucial in ensuring optimal eye health and visual outcomes.

Patient Education and Support

Being diagnosed with Granular Corneal Dystrophy can feel like staring into a foggy landscape, fraught with uncertainties. Hence, it's paramount to provide comprehensive patient education, drawing back the curtains of ambiguity to let in the light of understanding.

Educating About the Condition

Patients and their families should be informed about the genetic nature of GCD, the role of the TGFBI gene, and how the condition tends to progress over time. Providing a thorough understanding of the potential visual impact and likely course of the condition will empower patients, helping them prepare for potential changes and challenges that may lie ahead.

Support and Guidance

Guidance in managing the condition extends beyond the clinical environment. Encouraging patients to adopt suitable lifestyle modifications, such as wearing sunglasses or using artificial tears, can go a long way in mitigating discomfort and maintaining a good quality of life.

Moreover, emotional and practical support is crucial. Connection with support groups and counselling services can provide emotional relief, while educational resources can help patients better understand and manage their condition.

As ophthalmologists, we don't merely treat the eyes; we strive to illuminate the path for our patients, helping them navigate through the sandstorms of their conditions. Our role is to offer both a clinical and a guiding hand, providing clear-sighted advice and support in their journey with GCD.

To Conclude...

Navigating through the fascinating yet challenging landscape of Granular Corneal Dystrophy, we find ourselves standing at the intersection of genetics, vision, and patient care. As ophthalmologists, our role is more than diagnosing and treating eye conditions - it's about seeing the bigger picture, the human element behind each clinical case. Just as we assist our patients in achieving clearer vision, we too must constantly strive to refine our view of this evolving field. Here's to casting a keen eye on the future, as we continue to unmask the enigmas of our patients' eyes, one granule at a time.

Remember, in the grand landscape of ophthalmology, every grain of knowledge counts. With each new development, we're not just shedding light on the path ahead, we're truly helping to 'cornea-graph' the maps to better vision and patient care.

(1).jpg)