Educating Patients for Pars Plana Vitrectomy: An Essential Guide to Informed Consent and Aftercare

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a microsurgical procedure used by retina surgeons to perform a variety of operations. The first step in this procedure is to remove the "vitreous gel" that fills the back of the eye (hence "vitrectomy"). While a lot of eye surgery is performed in the front part of the eye (ie cataract surgery), retina surgeons perform surgery in the back portion of the eye. They access the back of the eye through the "pars plana" – this is a "safe zone" to work that avoids damage to the retina and crystalline lens (or implant from prior cataract surgery).

A variety of microsurgical tools, lenses, illuminating devices, and lasers are then used to achieve the surgical goal. PPV's can typically be performed under local anesthesia, and most patients leave the hospital within 1-2 hours after surgery.

What is Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV) and When is it Indicated?

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a surgical technique originally introduced by Robert Machemer. The pars plana approach to the vitreous cavity allows access to the posterior segment to treat many vitreoretinal diseases. This procedure requires a great deal of technical skill and knowledge to ensure good outcomes. A successful vitrectomy can restore vision and improve the quality of life in patients suffering from many vitreoretinal diseases. However, the procedure can also be associated with complications. Although the chances are low when performed correctly, these complications can cause severe patient morbidity and blindness.

Therefore, it is essential that clinicians have thorough knowledge regarding the topic, understand the procedure, when to use it, how to perform it, and post-operative management. A vitrectomy can be considered for a variety of clinical scenarios since it enables the operating surgeon to access both the vitreous and retina. Below we list when PPV is indicated based on the type of pathology affecting the vitreous and/or the retina.

The Importance of Informed Consent for Pars Plana Vitrectomy

One of the most common indications for a PPV is when there is pathology that opacifies the vitreous and thus reduces vision. One example is a non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage. Many diseases can cause vitreous hemorrhage, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, trauma, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment (RD), intraocular tumors, and retinal vascular diseases. Vitreous hemorrhage due to diabetic retinopathy can be treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections in some circumstances, and only in the absence of traction as well.

In many cases, vitreoretinal surgeons will proceed with PPV without an injection if it is dense and unlikely to resolve with conservative therapy. If the vitreous hemorrhage does not clear despite conservative measures, then a vitrectomy is needed.

Modern-day pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a common procedure employed by vitreoretinal surgeons to gain access into the posterior segment of the eye. This allows for the treatment of many conditions ranging from vitreous debris (floaters) and epiretinal membranes, to retinal detachments, subretinal hemorrhages, and intraocular tumors.

Since the development of the modern-day three-port vitrectomy system by Conor O’Malley and Ralph Heintz in 1974, there have been multiple advances in instrumentation. These advancements include smaller gauge instruments, vitrectomy machines that provide higher cut rates and more stable intraocular pressures (IOPs), and visualization systems, most recently with "heads up" three-dimensional viewing systems with 3D glasses.

Understanding the Procedure: Gaining Access and Performing the Vitrectomy

Informed consent - Obtaining informed consent from the patient — where risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery are discussed — is often the most important part of the procedure. In many cases, such as vitreous debris or an epiretinal membrane, surgery is not “necessary” and therefore, is an “elective” procedure. This step often occurs in the clinic, prior to going to the operating room (OR).

During this discussion, the patient also must be made aware of what to expect before, during, and after surgery. In addition to the risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery, the following questions should be answered and discussed with the patient prior to surgery:

• What do I wear?

• When do I stop eating/drinking?

• Can I still take my medications?

• Will I be awake or asleep?

• How long will the procedure take?

• How long is the recovery period?

• Do I have to position after surgery?

• What is my visual prognosis?

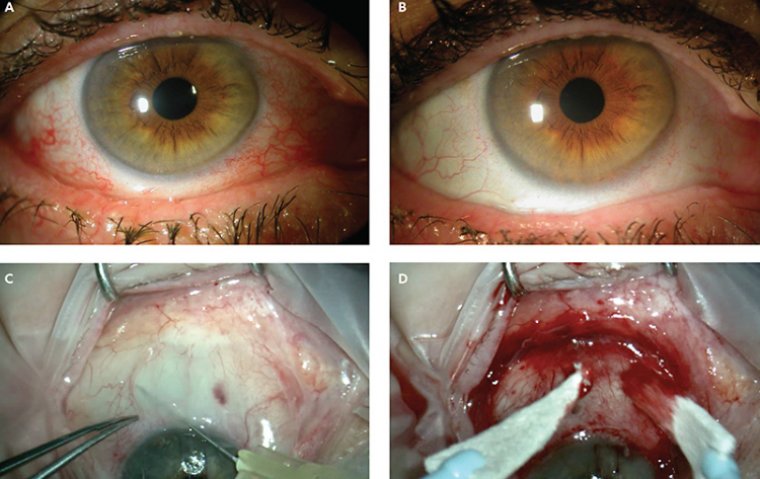

Failure to discuss these topics with the patient prior to surgery can (and likely will) result in an unhappy patient, regardless of the “outcome” of the procedure. Retrobulbar block Vitreoretinal surgical cases may require very delicate movements in close proximity to the surface of the retina. Therefore, limiting eye movement and patient comfort are addressed, in most scenarios, via a retrobulbar block to obtain akinesia and anesthesia. A typical retrobulbar block consists of 50% lidocaine and 50% bupivacaine.

The mixture is injected into the retrobulbar space into what is called the muscle cone, which is comprised of the four rectus muscles. The branches of the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III) run along the inside of the muscle cone and innervate muscles responsible for eye movement.

This is why injecting the anesthetic directly into the muscle cone does such a good job of providing akinesia and anesthesia. However, the optic nerve (cranial nerve II), which is responsible for vision, also runs inside the muscle cone.

Therefore, patients frequently lose vision after receiving a retrobulbar block for as long as the block has an effect, usually 6-8 hours.

Performing Indicated Procedures during Pars Plana Vitrectomy

Now the patient is ready for surgery. After entering the OR, everyone in the room pauses to agree on the patient, the eye being operated on, and the procedure being performed.

Next, a sterile preparation is used to clean the eye and surrounding skin, and the areas not being operated on are covered. The actual surgery part of this procedure is broken down into four steps:

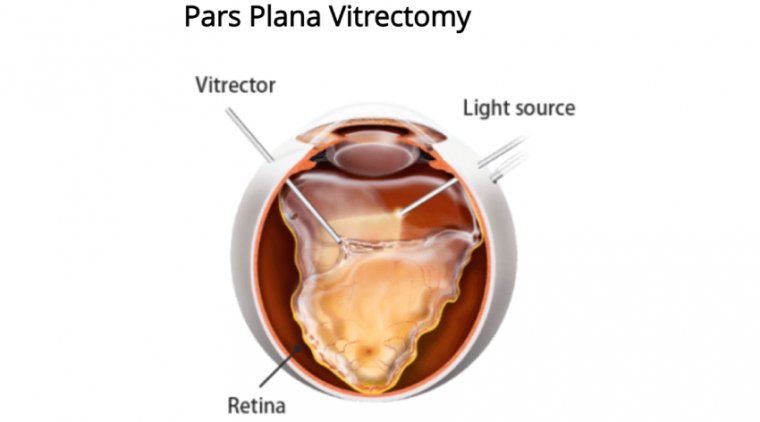

1. Gaining access - The term “three-port PPV” is used to describe the method of access to the posterior segment. A standard vitrectomy involves placing three cannulas in the eye through the pars plana, a relatively avascular area of the eye located approximately 3 mm to 4 mm posterior to the limbus between the pars plicata and ora serrata, the end of the retina.

The cannulas (or ports) allow for instruments to go in and out of the eye without the need for more incisions.

The three ports consist of an infusion line placed inferotemporally and two ports superonasally and superotemporally to allow for an illumination device in one hand and a “working instrument,” such as the vitreous cutter or grasping forceps, in the other.

2. Performing the vitrectomy - Before any work can be done in the posterior segment, the vitreous humour, known more simply as the vitreous, must be removed.

The vitreous, which fills the eye from behind the lens to the retinal surface, consists mainly of water; but, it also has a mixture of collagen, proteins, sugars, and salts. The vitreous is attached to the retina, so if you move through the posterior segment without removing the vitreous, it will create traction on both.

This can lead to retinal tears or detachments. Removing the vitreous, also called a vitrectomy, is the first step of every vitreoretinal procedure.

The vitrectomy is performed using a vitreous cutter. This instrument has a small opening, sometimes referred to as the "mouth," at the tip which opens and closes 5,000 to 10,000 times per minute.

This instrument aspirates vitreous into its mouth when open and cuts the vitreous when closed.

The vitreous is most adherent to the retina at the optic disc, the fovea (the center of the retina), the vessels, and the vitreous base. Care must be taken when removing the vitreous from these areas.

3. Performing the indicated procedure - Once the vitreous is removed, the surgeon can perform the indication for the procedure. Sometimes, removing the vitreous is all that is necessary, such as in cases of vitreous debris.

Some examples of common cases performed include retinal detachment repair and membrane peel. Membrane peels are required to repair epiretinal membranes or full-thickness macular holes.

The membranes are stained with a green or blue solution that helps the surgeon visualize the membrane and remove it using intraocular forceps. A retinal detachment repair involves first locating all of the patient's retinal tears.

Once identified, the tears are marked using intraocular cautery, and the retina is flattened and reattached by replacing the liquid fluid in the eye with an air bubble (this is called a fluid-air exchange).

Laser is then placed around the tears to “spot weld” the retina down in these locations; then the air is exchanged for an expansile gas that will slowly dissolve over one to two months.

4. Closing - Once the procedure is completed, then the cannulas are removed from the eye. When the cannulas are placed, they are usually done so at an angle to create what becomes a sealed incision once removed.

Sometimes, however, gas or liquid is noted to leak from the incisions. If this is the case, the incisions are closed using sutures.

It is important to make sure that the IOP is appropriate at the end of the case. If the pressure is too high or too low, there could be significant consequences in the immediate post-operative period.

Head Positioning and Aftercare for Pars Plana Vitrectomy Patients

If there is no air or gas bubble placed in the eye, then there are no head positioning requirements. However, if any amount of gas or air is placed in the eye, then positioning is needed.

The location of the pathology in the retina will determine what position and for how long the positioning is required. Common head positions include face down, head up, left side down, right side down.

These positions are necessary all day when patients are awake, usually with a 10-15 minute break every hour. If a face down position is required for an extended period of time (longer than three days), then a positioning assistance device is recommended.

These devices can relieve the pressure placed on the neck and back that comes with prolonged positioning. Eye drops consisting of an antibiotic and a steroid are used postoperatively in all vitrectomy cases.

Most patients require approximately one week of limited activity to facilitate proper healing after their surgery and are typically seen for follow-up one day, one week, and one month following the procedure.

The Advancements in Modern-day Pars Plana Vitrectomy

Modern-day retina surgery is a wonderful tool that physicians can use to improve, maintain, and save vision in patients who previously were destined for blindness. Understanding the basics of vitrectomy surgery can greatly improve the quality of care provided to the patient by all members involved in the patient’s care.

(1).jpg)