Glaucoma Medication Options

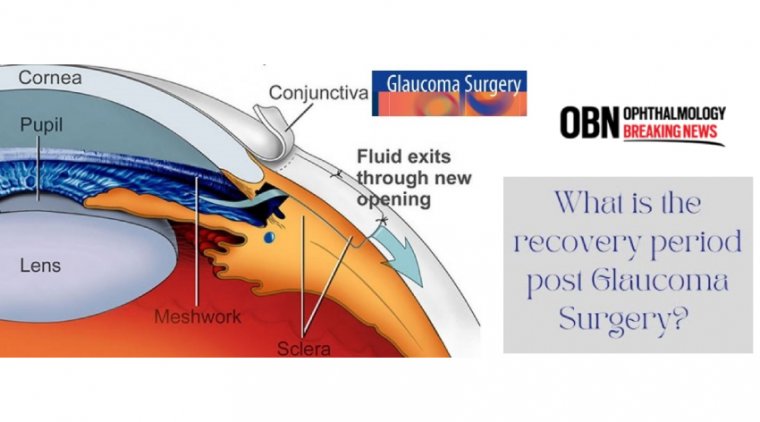

The most common treatments for glaucoma are eye drops and, rarely, pills. They work by lowering the pressure in the eye and preventing damage to the optic nerve. These eye drops won’t cure glaucoma or reverse vision loss, but they can keep glaucoma from getting worse.

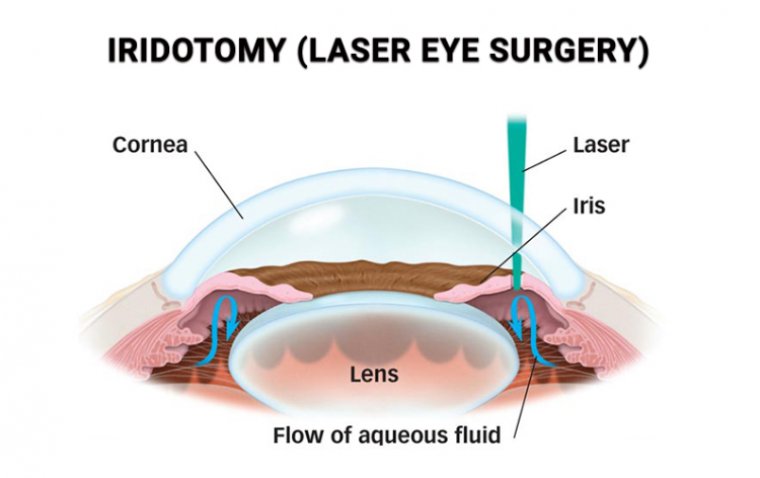

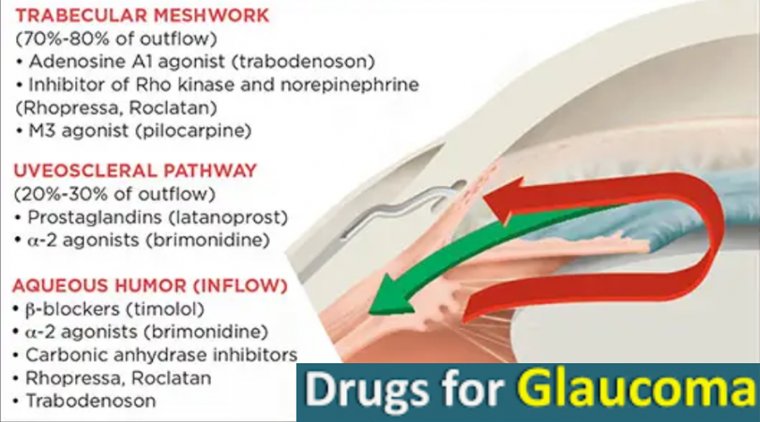

There are a number of different categories of eye drops, but all are used to either decrease the amount of fluid (aqueous humor) in the eye or improve its outward flow.

Sometimes doctors will prescribe a combination of eye drops. People using these medications should be aware of their purpose and potential side effects, which should be explained by a medical professional. Some side effects can be serious.

Since the approval of the first prostaglandin analogue in the 1990s, this class of medication has been the first-line treatment choice for doctors and patients with newly diagnosed glaucoma.

Today we have more treatment choices, including new categories of glaucoma medications, safer surgical options, and novel drug-delivery systems.

Although laser and surgical options may play a role in glaucoma treatment, the majority of glaucoma patients and those at risk of developing the disease are managed medically.

These medical therapies have advanced during the past several years, allowing for combined mechanisms of action in a single drop, alternative formulations that may limit the need for preservatives, and new methods for drug delivery.

The currently available options are fairly expansive and make it possible to better tailor the treatment regimen to the individual patient needs and pressure requirements.

Manufacturing Categories - Branded

When drops are prescribed for glaucoma, there are several factors to consider. First, the prescriber chooses between different medication manufacturing categories: branded, generic, and compounded.

When a new class of glaucoma medication is developed, they typically become first available as a brand-name medication. These drugs, which may include a single active ingredient or a combination, go through animal and clinical studies to prove their safety and efficacy.

After initial non-clinical animal studies, these products are typically tested in three phases of human clinical trials.

The Phase 1 clinical studies begin human dosing of the drug in which there is testing for tolerability in healthy individuals, ocular hypertensive patients, or patients with primary open-angle glaucoma.

Phase 2 trials are conducted to determine the minimum dose that is maximally effective in the target population.

Lastly, Phase 3 trials replicate the safety and efficacy of the drug in well-controlled independent trials. The new agent must demonstrate equivalence or superiority to an active control, such as timolol.

Generic

Once the patent for a medication expires, there is an opportunity for the active ingredient to be produced as a generic formulation.

To be approved, FDA generic drug applicants must show the generic medicine is the same as the brand-name in the following ways (per FDA.gov):

• The active ingredient in the generic medicine is the same as in the brand-name.

• The generic medicine has the same strength, dosage, and route of administration (such as oral or topical).

• The generic medicine is manufactured under the same strict standards as the brand-name medicine.

• The label is the same as the brand-name medicine's label (with certain exceptions). In the case of eyedrops, we also see this demonstrated in the same cap color among different drug classes.

• The generic medicine is bioequivalent to the brandname medicine. Generic manufacturers do not need to go through the same initial animal and clinical studies required of brandname producers to demonstrate safety and efficacy, thus their costs are typically lower.

Lower pricing may also result when there are multiple generic manufacturers for the same drug, producing competition in the market.

Compounded

Drug compounding is the process of combining, mixing, or altering ingredients to create a medication tailored to the needs of an individual. This includes the combining of two or more classes of FDA-approved glaucoma medication into one bottle.

Combination medications increase convenience by reducing the total number of drops requiring instillation. Data has suggested a synergistic benefit to intraocular pressure (IOP) control when drops are used in combination form.

Compounded drugs are not FDA-approved and typically not covered by insurance. Their benefits include lower cost and the ability to combine three or more drug classes (with two being the only combination option available in branded or generic forms).

There have also been compounded preservative-free formulations for classes not previously available in this preparation.

Drug Classes - Overview

Along with the previous categories, prescribers are presented with multiple classes of topical therapy. There are five commonly available types of glaucoma medication, and each lower IOP via different mechanisms.

Prostaglandin Analogues

Generic medication latanoprost has been available since 1996. It has the convenience of once daily dosing.

Amongst all classes, it demonstrates the greatest IOP lowering via increased aqueous humor outflow through the uveoscleral pathway. Latanoprostene bunod, approved in 2017, is a once-daily drop that releases latanoprost and nitric oxide (NO) on administration.

In addition to the action of latanoprost, NO increases conventional trabecular outflow, a novel mechanism of action.

Known side effects of latanoprost include iris pigmentation changes, darkening of the eyelid skin, eyelash growth, and periorbital fat atrophy. For most practitioners, prostaglandins are considered first-line treatment in the treatment paradigm.

Beta Blockers

Timolol, first approved by the FDA in 1978, reduces IOP by decreasing the production of aqueous in the ciliary body.

It can be dosed once or twice daily, depending on the preference of the prescriber or if being used in combination form.

Possible rare but serious side effects could include dizziness, eye pain/swelling/discharge, slow or irregular heartbeat, muscle weakness, mood changes, and coldness/numbness/pain in the hands or feet.

Avoid these medications in patients who have an asthma or COPD history or those with cardiac conditions such as heart block or severe heart failure.

Alpha Agonists

The most commonly utilized alpha agonist for the routine treatment of glaucoma is brimonidine. Approved in 1996, it both reduces aqueous humor production and stimulates aqueous humor outflow through the uveoscleral pathway.

Dosed at two or three times daily, it can be associated with dry mouth, ocular allergy with a red eye or red eyelids, tiredness or fatigue, low or high blood pressure and possible slowing of heart rate (less than with beta blockers), blurred vision, sensitivity to bright light, and headache.

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Brinzolamide (approved in 1998) and dorzolamide (approved in 1994) inhibit carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes present in ciliary processes of the eye, with the consequent reduction of bicarbonate and aqueous humor secretion.

They are dosed at two or three times per day. Adverse effects of topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are rare but include superficial punctate keratitis, acidosis, paresthesias, nausea, depression, and fatigue. So patients are not alarmed, explain that it is common for the drops to sting with instillation.

Rho-Kinase Inhibitors

Also known as ROCK inhibitors, this class of medication became available in 2017. It targets aqueous outflow at the level of the trabecular meshwork and has also been demonstrated in some studies to reduce the episcleral venous pressure (the venous pressure system surrounding the eye).

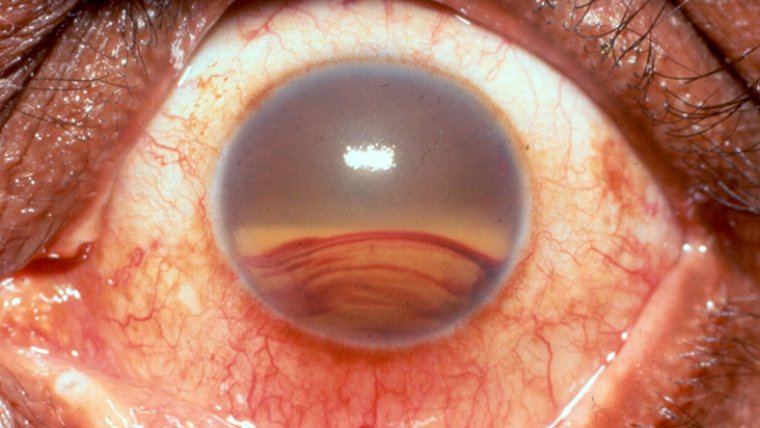

Netarsudil is used once daily, typically in the evening. The most common side effect seen is eye redness, sometimes significant.

Other potential sequelae include instillation site pain, corneal changes known as verticillata, and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Considerations & Education

Doctors consider multiple factors when prescribing topical therapy for glaucoma. What typically enters my mind when deciding the ideal treatment are convenient dosing, minimal side effects, lack of contraindications in health history, cost, and efficacy.

(1).jpg)