Researchers Develop Pig Retinal Cells to Advance Eye Treatments

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have successfully developed pig retinal organoids, opening new pathways for testing and advancing stem cell therapies for vision loss. The breakthrough, published in Stem Cell Reports, aims to address a significant challenge in ophthalmology—transplanting lab-grown photoreceptors to restore vision in degenerative retinal diseases.

Stem Cell Therapies Face Compatibility Barriers

The human retina contains light-sensitive photoreceptors that are crucial for vision. Damage to these cells due to disease or injury can lead to irreversible blindness. According to Dr. David Gamm, director of UW–Madison's McPherson Eye Research Institute, stem cell therapy is a promising approach to restoring lost photoreceptor function. However, testing these therapies in animal models has been difficult due to immune rejection of human cells in other species.

“Pig and human retinas share many key features, making pigs ideal for modeling human retinal disease and testing ocular therapeutics,” says Gamm. “By testing ‘human-equivalent’ photoreceptors in pigs, we can get a better sense of what these cells can do if they are not immediately attacked by the host animal.”

Pig Retinal Organoids: A Game Changer for Ophthalmology

In collaboration with the Morgridge Institute for Research, the Gamm Lab created pig retinal organoids—small tissue clusters that mimic the cellular interactions of a real retina. These organoids allow scientists to observe retinal development in a controlled lab environment.

“This is the first time that people have made pig retinal organoids,” says Kim Edwards, a graduate student in the Gamm Lab and first author of the study. “And this was the first time that people have done a comparison of human versus another species of retinal organoids.”

To develop these pig retinal organoids, researchers worked with pluripotent stem cells derived from pigs. They adjusted their existing protocols for human cells, reducing the development time by half to match the shorter gestational period of pigs.

“We were able to make a lot of retinal organoids from that, which was really exciting,” Edwards says. “It’s a good proof of concept to show that if we’re going to differentiate to a specific cell type, we really need to pay attention to the gestational differences and the inherent differences between the cells.”

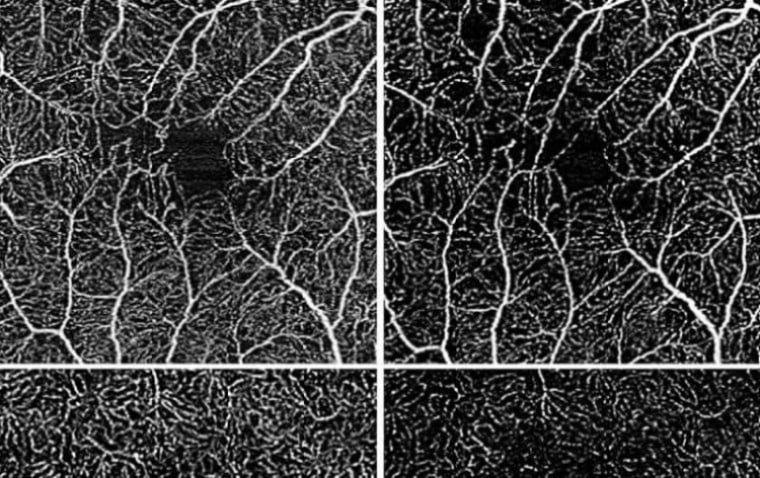

Advanced Gene Analysis Confirms Success

To verify the accuracy of the pig organoids, researchers employed immunocytochemistry techniques and single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). This analysis allowed them to map gene expressions and confirm the presence of key retinal cell types, such as photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells.

“They did a lot of magic using single-cell RNA-seq—things that we didn’t even think were possible,” Edwards says.

Beth Moore, a computational biologist from the Stewart Computational Biology Group at Morgridge, played a critical role in data analysis. The sequencing process involved tagging each cell with a barcode, sequencing them individually, and grouping similar cells based on gene expression patterns.

“It’s an unbiased and very comprehensive view of what genes are expressed in each cell type in the organoid,” says Moore. “It’s a different type of marker from the immunochemistry. It’s a different way to come to the same conclusion of identifying different cell types.”

Next Steps: Testing Pig Photoreceptors in Live Retinas

The next phase of the research involves transplanting pig-derived photoreceptors into pig retinas to assess their ability to integrate with existing retinal structures and potentially restore vision.

“We’re excited to show that you can grow these retinal organoids from different species and that a lot of groups across the world are starting to make them,” says Edwards. “It all starts with having good stem cells.”

The findings could pave the way for more effective stem cell-based treatments for vision loss, offering hope for millions affected by retinal degenerative diseases.

Reference:

Kimberly L. Edwards et al, Robust generation of photoreceptor-dominant retinal organoids from porcine induced pluripotent stem cells, Stem Cell Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2025.102425

(1).jpg)