Advancements in Treatment of Open-Angle Glaucoma

Most people who have open-angle glaucoma feel fine and do not notice a change in their vision at first because the initial loss of vision is of side or peripheral vision, and the visual acuity or sharpness of vision is maintained until late in the disease.

By the time a patient is aware of vision loss, the disease is usually quite advanced. Without proper treatment, glaucoma can lead to blindness.

Because open-angle glaucoma has few warning signs or symptoms before damage has occurred, it is important to see a doctor for regular eye examinations. If glaucoma is detected during an eye exam, the eye doctor can prescribe a preventative treatment to help protect vision.

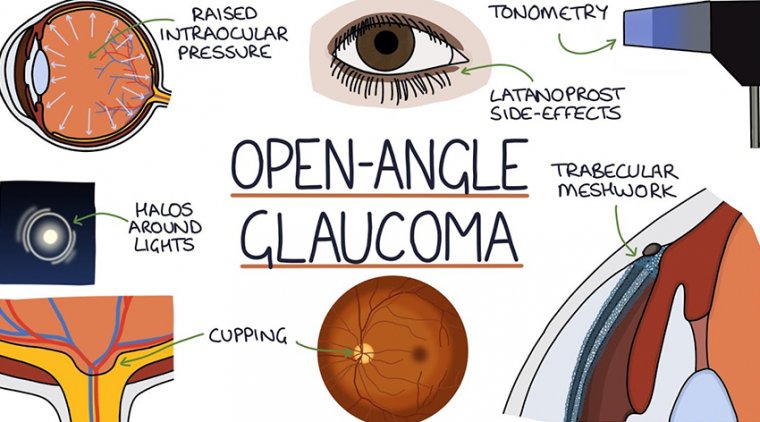

In open-angle glaucoma, the angle in the eye where the iris meets the cornea is as wide and open as it should be, but the eye’s drainage canals become clogged over time, causing an increase in internal eye pressure and subsequent damage to the optic nerve.

It is the most common type of glaucoma, affecting millions, many of whom do not know they have the disease.

There are many effective and different treatments for open-angle glaucoma, but the one unifying concept is that all current treatments are designed to lower eye pressure.

Treatments for open-angle glaucoma include medications (usually eye drops), laser trabeculoplasty (a procedure that improves drainage of eye fluid through the spongy tissue located near the cornea, called the trabecular meshwork), and surgery.

There is also research, some in clinical trials already, for new treatments that do not focus only on lowering eye pressure, but also on promoting the health of the optic nerve.

Glaucoma causes irreversible blindness and it is caused by ocular hypertension, which damages the optic nerve and results in visual field loss.

There is no cure, but the disease can be managed with pharmacologic therapies, among other more invasive treatments, that lower and stabilize intraocular pressure (IOP).

Joseph F. Panarelli, MD, associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and Sahar Bedrood, MD, PhD, a glaucoma specialist at Acuity Eye Group, and assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the USC Roski Eye Institute, Los Angeles, recently spoke on the current state and future of glaucoma therapy and how compliance may not be an issue in the coming years.

IOP & Glaucoma Progression

IOP reduction is the only known modifiable risk factor for open-angle glaucoma. However, studies have shown that disease progression and blindness are still possible even in patients on maximum medical therapy.

How IOP factors into visual field loss isn’t entirely clear. According to Dr. Bedrood, one theory—known as the stress/strain model—is that IOP strains the sclera and optic nerve, causing apoptosis and loss of retinal ganglion cells.

Another theory—the vascular theory—is when the blood vessels in the optic nerve don’t get enough oxygen, which leads to apoptosis, nerve fiber layer loss, and, eventually, visual field loss. No two cases of glaucoma are alike, and progression rates vary from person to person.

“Some patients who have a very strong genetic component are going to progress very quickly, and some, not so much,” Dr. Bedrood said. Co-morbidities such as sleep apnea and IOP fluctuations are other risk factors for visual field progression and greater visual field loss in certain patients.

The causes of IOP fluctuations are multifactorial and can be due to poor treatment compliance, genetics, and a decline in treatment effectiveness over time. “After 10-plus years of treatment, some of those treatments that initially worked may not work as well,” Dr. Bedrood said.

“Sometimes, patients respond really well in the beginning and then over a couple of months or years they don’t, and then they fluctuate their IOP.” Over a decade, selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) will wear off, requiring patients to have a touchup or a second round of treatment.

Patients may develop an allergy or intolerance to glaucoma drops as well. “Over a course of 10 years, a lot can change,” Dr. Bedrood said. “Their rate of progression can fluctuate. Their tolerance of drugs can fluctuate.

Oftentimes after 10, 15, or 20 years, we’re looking at other modalities of treatment like surgery or something that can regulate their pressure a little bit better—other additional drugs, for instance.”

Personalized Treatment Plan

Prostaglandin analogues—such as bimatoprost, latanoprost, tafluprost, and travoprost—are common first-line treatments for patients with newly diagnosed glaucoma. They are non-invasive and can reduce IOP by 25% to 30% with once-daily dosing, which can be appealing to patients.

Just because they are the most common firstline treatment doesn’t mean they are the best. Clinical trials have shown that SLT is just as safe and effective as drops, with a 20% reduction in IOP that lasts for up to three years without the hassle of daily medication.

However, patients are often uncomfortable with the idea of a procedure initially and underestimate the burden of daily medication. Dr. Panarelli believes the pros and cons of SLT versus daily drops is a conversation worth having with patients early on in the treatment process.

“I think it’s worth having a discussion with them regarding whether they prefer to start topical therapy or whether they would like to proceed with laser trabeculoplasty, especially now with data from the LiGHT trial,” he said.

Regardless of the initial approach, certain patients will ultimately progress. When it is necessary to advance treatment, these patients may need a more aggressive approach.

“It’s a big decision for me to add another medication,” he said, adding that if a second medication is necessary, his preference is to go straight to a fixed-combination agent for those he suspects are “rapid progressors.”

When selecting a treatment approach, clinicians must consider patient preferences, cost, and other factors impacting compliance. For example, patients with advanced glaucoma may be taking six to 10 drops a day.

Drops that contain preservatives may cause ocular surface disease such as dry eye, leading to patient discomfort and decline in quality of life. Drop burden and unwanted side effects all impact compliance rates.

“A lot of us are trying to decrease the number of total drops and maybe even move toward some of the preservative-free agents for a lot of our patients,” Dr. Panarelli said.

“I think the medication landscape is changing, but I think the biggest thing we have to keep in mind is cost and compliance with all of our patients. We’re trying to find the most effective medicine in the least number of bottles.”

Newly Approved Agents

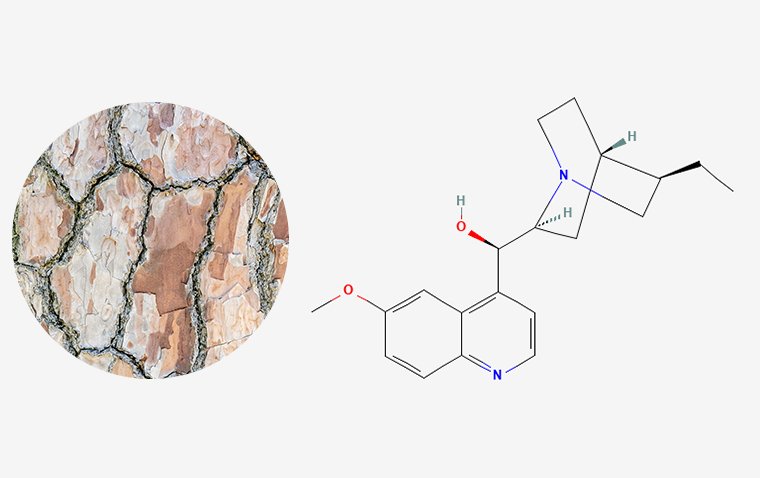

For the first time in decades, two new classes of drugs have been introduced for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma: latanoprostene bunod and netarsudil. The agents have different mechanisms of action and could be disease modifying.

Netarsudil is a Rho-kinase inhibitor that targets the outflow pathway. Netarsudil is a drug for the treatment of glaucoma.

In the United States in 2017, the FDA approved a 0.02% ophthalmic solution for the lowering of elevated IOP in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, targeting the trabecular meshwork directly.

Netarsudil is unique in that “none of the other medicines out there on the market actually work at the level of the trabecular meshwork,” Dr. Panarelli said. “By inhibiting Rho-kinase, we’re able to relax some of the actin and myosin contractions.

By relaxing those contractions, we’re able to enhance outflow through the physiologic outflow pathway.” It has other mechanisms of action as well and has the potential to lower episcleral venous pressure (EVP).

“This is something that we do not see with other medication classes,” Dr. Panarelli said. Latanoprostene bunod is a new version of a prostaglandin that also has a nitric oxide donating moiety.

The exact mechanism of action is somewhat complex, according to Dr. Panarelli, but it’s believed to have a number of benefits including smooth muscle relaxation/ enhanced outflow through the trabecular pathway as well as increased uveoscleral outflow.

Fixed-combination netarsudil/latanoprost is another new drug on the market, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2019. The once-daily drug also reduces IOP by enhancing aqueous outflow through both the trabecular and uveoscleral pathways.

“What is unique about the netarsudil/latanoprost combination is this is really one of the first times we actually had a medicine go up against latanoprost alone,” Dr. Panarelli said.

“Latanoprost is one of our bigger guns out there, so it is encouraging to see that we have these new medicines, and it’s nice to see data that does support good efficacy with these different agents.”

Although clinical trial data support the efficacy of these agents, how exactly to use them in the real world and in whom are questions clinicians are currently wrestling with.

“It’s nice to have some new medicines that are out there on the market because I think they all fit into our armamentarium somewhere,” Dr. Panarelli explained. “I think, as clinicians, we are still figuring out exactly how to use these medicines and how to mix them in with our other available agents.”

If a patient is not responding on a prostaglandin analogue, Dr. Panarelli will switch them from either latanoprost to latanoprostene bunod or from latanoprost to combination latanoprost/netarsudil.

He also believes there is a place for the medications in patients with low-tension glaucoma, who are traditionally some of the most difficult patients to treat. Dr. Panarelli has found netarsudil to be particularly useful in these patients because it lowers EVP.

“Some of my patients can get down to that singledigit range, which is a number I often cannot get with traditional carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, or alpha-2 agonists, or even beta blockers,” he said.

There are some situations in which Dr. Panarelli will use netarsudil as a first-line agent. For example, if a patient is uncomfortable with the potential side effects of increased iris pigmentation and periorbital fat atrophy that come with a prostaglandin analogue, he may recommend netarsudil.

He may also recommend netarsudil if the patient is already on an oral beta blocker or is hesitant to start on a beta blocker generally. “I have had several patients where I have talked about having surgery,” he said.

“We started netarsudil, and it’s actually been great in that they have gotten to their target IOP without me having to perform a trabeculectomy, which is huge for my patients.”

Emerging Therapies

A number of treatments for glaucoma are not yet approved but currently in development. For example, bimatoprost sustained release (bimatoprost SR) is a first-in-class, sustained-release, investigational, biodegradable implant for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma.

If approved, Dr. Panarelli said he believes bimatoprost SR could be “a game-changer” in that it completely takes patient compliance out of the equation and significantly reduces the overall treatment burden glaucoma patients face.

With bimatoprost SR, “all we ask [patients] to do is to come once every several months to get their treatment,” Dr. Panarelli said.

“This can have a meaningful impact for our patients. It is one thing to talk to a patient and tell them that they are going to have an injection once every four to six months for the rest of their lives, but if we can give a patient a loading dose of a medicine and not need to reinject them from anywhere from one to (maybe) three years, that will resonate well.”

The big unknown with the implant is safety. Will there be any complications or adverse effects from an injectable form of medicine delivered into the eye every six months?

Although data are limited to abstracts presented during conferences such as the Academy of Ophthalmology and American Glaucoma Society, Dr. Panarelli considers the safety and efficacy of bimatoprost SR to be positive so far.

“We have questions regarding issues with the cornea, and we have concerns about infection,” Dr. Panarelli said. “One of the things that has impressed me most is the fact that a lot of patients (up to 80%) who receive three doses over the first year did not need to be rescued over the next year that they were followed.”

Initially, Dr. Panarelli sees a place for bimatoprost SR as a second-line treatment when a patient is progressing or not achieving the IOP reduction needed on a prostaglandin or after SLT.

Once clinicians become more comfortable with the injection and have less concerns about the safety profile, clinicians may start with the injection rather than topical therapy.

“If we can show very good safety profiles for these medicines, I think we are going to see a lot of physicians using this treatment early in their treatment algorithm,” he said.

Improving Compliance

One of the primary issues in glaucoma is patient compliance. Up to 60% of glaucoma patients are non-compliant with daily drops. The reasons for this are multifold. First, glaucoma patients are generally older (people over age 60 are at increased risk for the disease).

Second, glaucoma is a life-long disease. Patients may tire of daily drops and may struggle with opening the bottle or even getting the drops in the eye correct as they age. “They physically have to open up the bottles and place it in their eyes every single day,” Dr. Bedrood said.

“That act is very different than taking a pill, and it is oftentimes more difficult for patients.” Cost is a frequent issue as well, as eye drops are often more expensive than generic medications for other conditions.

To address this, Dr. Bedrood suggests providing patients with coupons and enrolling them onto special programs where they can get lower prices. Glaucoma is also asymptomatic, causing patients to be less aware of their disease.

“Patients think, ‘Oh, I am fine. I am not feeling anything, I am not seeing any differently, and I will skip my dose today,’” Dr. Bedrood pointed out. Dr. Panarelli said ophthalmologists talk about glaucoma being a silent thief.

However, it can be an issue for patients. “That is a big problem for our patients,” he explained. “They don’t physically see the need often to come to these appointments, or they don’t see the need to take their drops quite like some other conditions that are possibly affecting them.”

Dr. Bedrood stresses the importance of having frank conversations with patients on the importance of compliance, and if compliance remains an issue telling them pointblank they could face surgery. She recommends asking how they’re doing on the medication and if they are able to open the cap.

She even asks them to demonstrate how they are administering the drops into their eyes to ensure they have the proper technique. According to Drt. Bedrood, clinicians can also involve family members and/or caregivers to help as well.

“If a family member is present, I usually like to ask them, ‘Who is giving the drop, and how often?’ It places kind of an onus of responsibility on whoever is in the room to help with this whole regimen,” she said.

Compliance Issues

If compliance issues on drops persist despite these strategies for improvement, the patient is left SLT or minimally invasive surgery. Clinicians must make this clear. “I talk about surgery with patients because it perks their ears up and they say, ‘Oh, wait, I do not want surgery,’”

Dr. Bedrood said. “And sometimes it reminds them that maybe it is better for them to use the drops.” Despite these potential challenges, both physicians agree that, with all the new agents on the horizon, it is an exciting time in the field of glaucoma.

“The sustained release, the implants, the ocular inserts, all of these things promise a way to deliver medications without having the patients do it,”

Dr. Bedrood said. “Having it in a very sustained, steady way is a really exciting part of our future in glaucoma. I think that it will really help our patients in the long-term.”

(1).jpg)