All About Irido-Corneal Endothelial Syndrome

The iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome is a developmental disorder of the eye characterized by acquired nontraumatic corneal edema, progressive abnormalities of the iris, and elevated intraocular pressure.

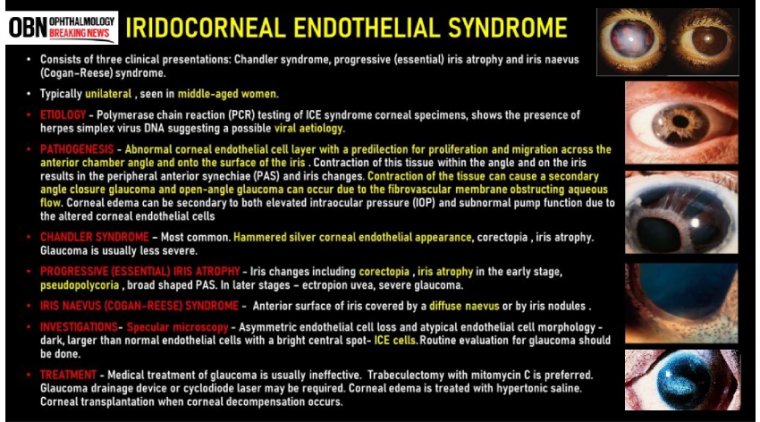

Three subcategories of ICE syndrome are commonly recognized: essential iris atrophy, the iris nevus syndrome (Cogan–Reese syndrome), and Chandler's syndrome.

Iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome describes a group of eye diseases that are characterized by three main features:

- Visible changes in the iris (the colored part of the eye that regulates the amount of light entering the eye)

- Swelling of the cornea, and

- The development of glaucoma (a disease that can cause severe vision loss when normal fluid inside the eye cannot drain properly)

ICE syndrome, is more common in women than men, most commonly diagnosed in middle age, and is usually present in only one eye. The condition is actually a grouping of three closely linked conditions: Cogan-Reese syndrome; Chandler's syndrome; and essential (progressive) iris atrophy.

The cause of ICE syndrome is unknown, however there is a theory that it is triggered by a virus that leads to swelling of the cornea.

While there is no way to stop the progression of the condition, treatment of the symptoms may include medication for glaucoma and corneal transplant for corneal swelling.

ICE syndrome is sporadic in its presentation as there is no correlation or association with any ocular or systemic disease.

It is characterised by the abnormal proliferation of corneal endothelium and progressive obstruction of the irido-corneal angle, which in turn leads to structural and functional iris abnormalities and ultimately visual function loss.

It is usually unilateral and typically affects women in the third to fifth decade of their lives.

The three variants of ICE syndromes share the same pathogenic mechanism, which is characterised by the normal corneal endothelial cells being replaced with more epithelial-like cells that migrate into the surrounding tissues.

This leads to varying degrees, dependent on the causative subtype, of corneal oedema, iris atrophy and secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

The altered endothelium migrates posteriorly beyond the Schwalbe line to obstruct the irido-corneal angle and at times onto the peripheral iris forming an abnormal basement membrane. Subsequent contraction of the new tissue can induce pupil shape anomalies and iris atrophy.

The combination of angle obstruction and corneal oedema leads to a raised intraocular pressure (IOP) giving rise to secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

The true aetiology of ICE syndrome still remains unknown. Literature has described a series of possible triggers, however, its exact aetiology or aetiologies have been an ongoing debate for over a century.

A common aetiology, however, is thought to be due to underlying viral infections with herpes simplex virus (HSV) which can trigger inflammation of the corneal endothelium and subsequent pathogenesis.

This was first hypothesised after a study carried out in 1994 which found HSV-DNA in more than 60% of the tested samples.

First diagnosis might be obtained from a routine ocular examination, following visualisation of an abnormal corneal endothelium or via gonioscopy when evaluating the anterior chamber angle for those suspected with glaucoma.

Otherwise, the usual index presentation that patients may report is a change in shape or position of the pupil. Alternatively, presentations may also vary from monocular pain, blurry vision or halos around lights due to glaucoma.

With symptoms overlapping across all three variants, distinction between each subtype can only be established from a clinical exam and a full ophthalmic work-up.

Subtypes

1. Chandler Syndrome:

This is the most common subtype, accounting for around 50% of all cases of ICE syndrome. In comparison with the other entities this subtype usually presents with a greater degree of corneal pathology and oedema.

Arriving at the diagnosis can be a challenging as majority of the patients are found to not have any iris abnormalities until the later stages of the disease. However, compared with the other subtypes it is least likely of the three to have IOP rise.

2. Progressive Iris Atrophy:

As opposed to Chandler syndrome, iris abnormalities in this particular variant are robust and progressive over time. Common findings include: polycoria, corectopia, iris hole formation, ectropian uveae and iris atrophy.

3. Cogan-Reese Syndrome:

Associated with iris abnormalities, the characteristic finding in this subtype is the presence of multiple iris pedunculated nodules.

ICE syndrome should be considered within the differential diagnosis for any young to middle-aged (especially female) adult presenting with unilateral glaucoma, corneal oedema and / or iris anomalies.

The key difference between each subtype that allow for distinction is the type / severity of iris abnormality.

A full ophthalmic work-up is essential, in particular, assessment of visual acuity and IOP. Evaluation of the anterior chamber angle for high peripheral anterior synechia (PAS) with gonioscopy is also an important aspect of the work-up because as many as 82% of patients with ICE syndrome can have glaucoma as a complication.

Comparatively, in the presence of corneal oedema, changes of the anterior chamber angle structure might be better detected through the use of ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) as it does not allow visualisation with gonioscopy.

A slit-lamp examination is also a vital part of the work-up as it allows identification of any corneal and iris abnormalities. Corneal endothelial irregularity on a slit lamp examination will give a ‘beaten bronze’ or ‘hammered silver’ appearance.

Although predominantly a unilateral disease, bilateral cases of ICE syndrome have been reported. It is therefore imperative the contralateral unaffected eye is given the same level of attention and work-up as the affected eye.

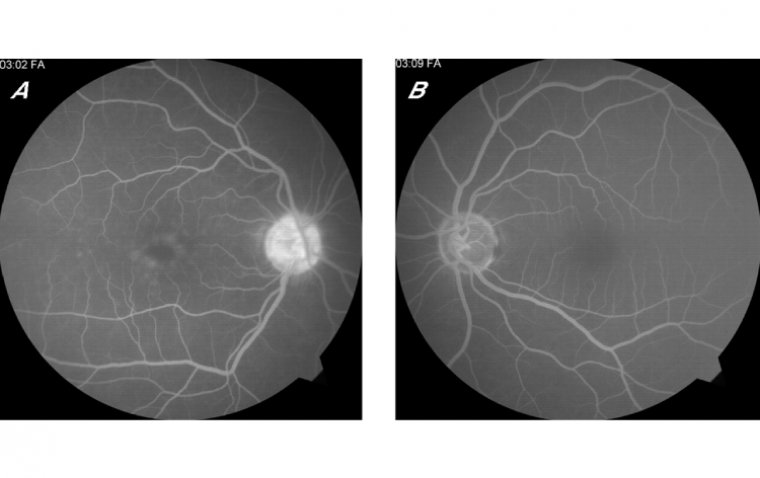

Lastly, a useful diagnostic tool used for confirmation is specular microscopy. A notable feature present on a cellular level is the atypical endothelial cell morphology.

On specular photomicrograph, this appears as large dark cells with light peripheral borders and central highlights. As it’s specific to ICE syndrome it has been referred to as ‘ICE cells’.

The main differential of ICE syndrome that must be ruled out is posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPMD).

PPMD is an autosomal dominant disease that is not only similar on a microscopic level (multi-layered endothelial cells that look and behave like epithelial cells) but also share similar manifestations such as corneal oedema, irido-corneal adhesion and raise IOP.

Factors that allow for differentiation are: the fact that PPMD is inherited and bilateral and specular microscopy shows typical vesicles and bands.

Although there are objective differences between each subtype, the diagnosis can still pose a challenge in clinical practice as a large percentage of cases appear in mixed forms.

Irrespective of the causative subtype, the mainstay of treatment revolves around the prevention and management of the visual impairing complications of ICE syndrome such as corneal oedema or glaucoma. This can be achieved with both medical and surgical treatment options.

Raised IOP and corneal oedema can be addressed with topical medications and aqueous suppressants, e.g. prostaglandin analogues. In addition, topical hypertonic saline solutions can be used to help ameliorate symptoms of corneal oedema as it works by dehydrating the cornea.

If medical management is unsuccessful in controlling the raised IOP surgical options must be sought. Procedures such as trabeculectomy with anti-fibrotic agents and use of aqueous shunts have been found to be effective in controlling raised IOP in ICE syndrome patients.

However, the long-term effectiveness of these procedures is questionable with the five-year survival rate reported as low as 29% vs. 53%, for trabeculectomy with anti-fibrotic agents and aqueous shunts patients, respectively. Similarly, keratoplasty can be used for the treatment of corneal decompensation.

The prognosis of patients with ICE syndrome depends on the timing of diagnosis and effectiveness of treatment. Where surgical intervention has been sought the prognosis tends to be more guarded.

In conclusion, ICE syndrome consists of three entities: Chandler syndrome, progressive iris atrophy and Cogan-Reese syndrome. A clinical history and a full ophthalmic exam including assessment of visual acuity and IOP are essential to reach a working diagnosis.

If suspected, specular microscopy and gonioscopy must be performed to confirm the presence of ICE cells and PAS for definite diagnosis.

Treatment, regardless of subtype, is prevention and management of visual impairing complications such as secondary glaucoma and corneal oedema. Surgical interventions have variable success rates thus early diagnosis is beneficial.

(1).jpg)