Breakthrough Trial Offers Hope for Late Amblyopia Treatment

In children with amblyopia, often referred to as "lazy eye," one eye exhibits weaker vision than the other due to various factors. This weaker eye may struggle with focusing, misalignment due to strabismus, or vision obstruction from conditions like cataracts or droopy eyelids. Consequently, the brain tends to prioritize signals from the stronger eye, causing a gradual decline in vision for the weaker eye.

Early intervention for amblyopia involves covering the dominant eye with a patch, encouraging the brain to allocate more attention to the weaker eye and thereby improving its vision. However, this approach is most effective when initiated before the age of 5 or 6. Beyond this critical period, the brain's ability to rewire its visual circuits diminishes, making vision loss more challenging to reverse.

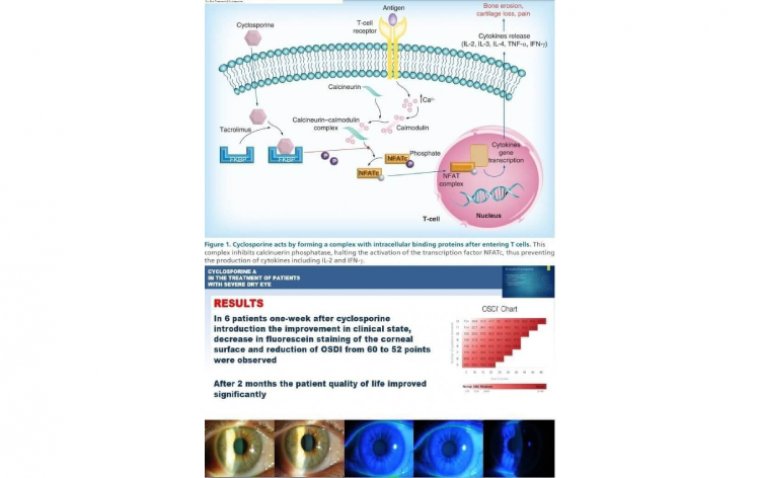

Recent research has shown that specific drugs can potentially reopen this critical period. In 2010, neuroscientist Takao Hensch, Ph.D., working at the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children's Hospital, published a study in the journal Science indicating that drugs like donepezil (commonly known as Aricept), primarily used to treat Alzheimer's disease, were able to reverse amblyopia in a mouse model, even after the typical visual critical period had passed.

This discovery inspired a small open-label clinical trial conducted at Boston Children's Hospital, which has raised hopes for restoring lost vision in older children and adults with amblyopia. While the observed improvements in vision were not uniform and relatively modest, they remained stable over time. This promising outcome opens the door to further research, including larger, placebo-controlled trials, which may explore the efficacy of different drugs and the potential benefits of combined visual stimulation techniques.

"This study was a bench-to-bedside proof of concept that brain plasticity can be rekindled. We hope it will inspire a larger-scale, placebo-controlled trial,” said Hensch.

David Hunter's Collaboration with Takao Hensch

Over a decade ago, David Hunter, MD, Ph.D., who serves as the chief of ophthalmology at Boston Children's Hospital, became aware of Takao Hensch's research findings on critical periods. Dr. Hunter found these findings highly intriguing. He recalls the moment when Hensch approached him with the idea of translating these results from laboratory studies to human applications, saying, "I have these results in the lab and want to bring them to humans." Dr. Hunter recognized this as a unique opportunity.

Given that donepezil, a medication known for enhancing acetylcholine levels, was already in use for cognitive improvement, Dr. Hunter believed initiating a clinical trial would not be overly challenging. He enlisted the expertise of ophthalmologist Carolyn Wu, MD, to design and lead the trial. With the backing of the Boston Children's Translational Research Program, the clinical trial was set in motion.

"We were able to go straight from mice to humans without having to go through years—if not decades—of preparation," Hunter says.

A Decade of Research

Nevertheless, the timeline for the process exceeded the initial expectations of Wu and Hunter. They first needed FDA approval to use donepezil for a novel purpose. Following this, they collaborated with a pharmacy to produce custom pills, each containing half the typical donepezil dosage prescribed for Alzheimer's patients.

Enlisting a sufficient number of older participants presented its own challenge, as most individuals over the age of 12 no longer attended clinic visits for amblyopia. Dr. Wu emphasizes the enthusiasm and exceptional compliance displayed by eligible patients, underscoring their vital role in clinical research.

Ultimately, the study enrolled a total of 16 participants, with an average age of 16, spanning from nine to 37 years old. All of these participants had previously undergone eye patching treatment but had discontinued due to the lack of further vision improvement.

Before commencing donepezil treatment, children under the age of 18 adhered to a four-week period of patching their weaker eye for at least two hours daily. To encourage adult participation, this requirement was waived for them. Subsequently, children were administered a daily dose of 2.5 mg of donepezil while continuing to patch, whereas adults received 5 mg. If, after four weeks, their vision had not improved by a minimum of one line (equivalent to five letters) on the eye chart, the dosage was escalated. Dosage limits were set at 7.5 mg for children and 10 mg for adults.

Promising Results: Vision Improvement in Amblyopia with Donepezil Treatment

After a 12-week treatment period, participants experienced an average improvement of 1.2 lines on an eye chart compared to their baseline. While not everyone responded, four out of the 16 participants showed improvements of two lines or more. Remarkably, these visual enhancements persisted for ten weeks after the discontinuation of donepezil, regardless of whether they were children or adults.

Dr. Wu comments, " The good news is that there were gains in visual acuity for some patients, none had significant side effects, and the improvements were maintained even after stopping treatment."

Dr. Hunter and Dr. Wu are currently exploring various avenues for conducting a larger-scale trial. One option involves collaborating with other prominent research centers nationwide specializing in amblyopia treatment.

In a potential larger trial, researchers could explore different donepezil doses or formulations, investigate alternative drugs that enhance visual plasticity, or even consider a combination of drug treatment and interventions such as video games, which also elevate acetylcholine levels. The goal is to achieve more substantial and clinically significant improvements—potentially four to five lines on the eye chart.

Dr. Hunter emphasizes, “This is a base hit, not a home run. But we're excited that we've made progress."

Reference

Carolyn Wu et al, Durable recovery from amblyopia with donepezil, Scientific Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-34891-5

(1).jpg)