The Relationship Between Blood Pressure and Intraocular Pressure in Glaucoma Risk

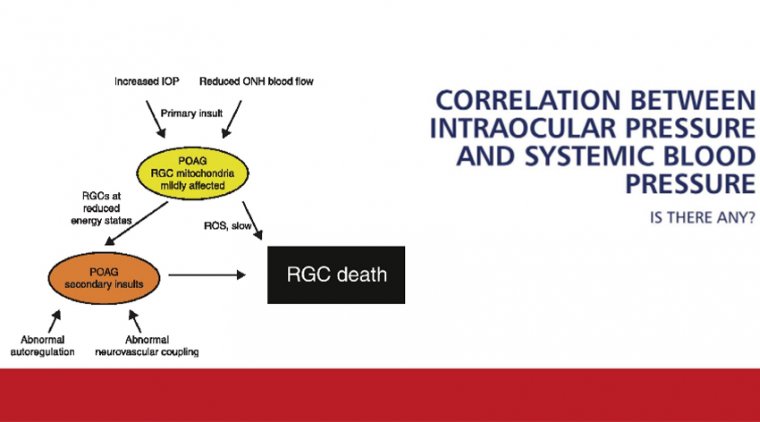

Evidence suggests that ocular perfusion pressure is a strong risk factor for glaucoma. Ocular perfusion pressure is the relationship between the eye pressure (intraocular pressure or IOP) and the blood pressure. An imbalance between these pressures can affect the optic nerve and potentially lead to glaucoma, a group of eye conditions that damage the optic nerve, often resulting in vision loss.

The Impact of Blood Pressure on Eye Health

Low Blood Pressure and Glaucoma

If the blood pressure is low, especially when the intraocular pressure (IOP) is elevated, it becomes difficult for blood to reach the eye. This impedes the supply of oxygen and essential nutrients to the optic nerve and other ocular tissues, while also hindering the removal of waste products. Over time, this inadequate blood flow, or hypoperfusion, can lead to optic nerve damage and progression of glaucoma.

Even individuals with normal eye pressure may experience inadequate ocular blood flow if their blood pressure is naturally low or reduced due to antihypertensive medications. This can deprive the eye of necessary nourishment, leading to optic nerve damage.

The Body's Autoregulatory Mechanisms

Under normal circumstances, the body adjusts to changes in blood pressure, body position, and other factors to maintain consistent blood flow to vital organs like the brain and eyes. This process, known as autoregulation, ensures that tissues receive adequate oxygen and nutrients despite fluctuations in systemic blood pressure.

However, in some individuals, these autoregulatory mechanisms may be impaired or insufficient. As a result, ocular tissues may not receive adequate blood supply, increasing the risk of glaucoma progression due to optic nerve ischemia.

The Association Between Intraocular Pressure and Systemic Blood Pressure

Population-based studies have found an association between intraocular pressure (IOP) and systemic blood pressure levels. Higher systemic blood pressure can lead to increased IOP due to several mechanisms:

• Increased Aqueous Humor Production: Elevated blood pressure may increase ciliary body blood flow and capillary pressure, leading to increased production of aqueous humor, the fluid in the front part of the eye.

• Reduced Aqueous Outflow: High blood pressure can raise episcleral venous pressure, impeding the outflow of aqueous humor and resulting in elevated IOP.

Conversely, aggressive lowering of systemic blood pressure, especially sudden reductions, may decrease ocular perfusion pressure, potentially worsening glaucoma.

Clinical Implications and Patient Concerns

Patients often express concerns about the relationship between their blood pressure and intraocular pressure. Those with hypertension may worry about developing glaucoma, while others may believe that their elevated blood pressure directly increases their IOP.

It's important to address these concerns by explaining that while there is an association between blood pressure and IOP, the relationship is complex and not fully understood. High blood pressure does not necessarily cause high IOP, and vice versa.

Conflicting Research Findings

Studies on the relationship between systemic blood pressure and glaucoma risk have yielded conflicting results:

• Rotterdam and Beaver Dam Eye Studies: These studies reported a higher risk of primary open-angle glaucoma associated with high blood pressure.

• Barbados Eye Study: In contrast, this study found that lower blood pressure was associated with an increased risk of glaucoma.

These discrepancies highlight the complex interactions between blood pressure, IOP, and glaucoma development. Factors such as ocular perfusion pressure, vascular health, and individual patient characteristics play significant roles.

Managing Blood Pressure in Glaucoma Patients

Importance of Optimal Blood Pressure Control

For patients with glaucoma, managing systemic blood pressure is crucial. Both high and low blood pressure can have adverse effects on ocular health:

• High Blood Pressure: May contribute to increased IOP and optic nerve damage due to vascular dysregulation.

• Low Blood Pressure: Especially nocturnal hypotension, can reduce ocular perfusion pressure, leading to optic nerve ischemia.

Coordination with Healthcare Providers

Patients should work closely with their primary care physicians and cardiologists to optimize blood pressure control. Adjustments to antihypertensive medication regimens may be necessary to avoid nocturnal hypotension, which has been linked to glaucoma progression.

For instance, taking blood pressure medications in the morning rather than at night may help maintain adequate ocular perfusion pressure during sleep.

Lifestyle Recommendations

Promoting a healthy lifestyle can benefit both systemic and ocular health:

• Regular Exercise: Engaging in moderate physical activity can help regulate blood pressure and may reduce IOP. However, patients should avoid activities that involve inverted positions, such as certain yoga poses, which can increase IOP.

• Balanced Diet: Consuming a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids supports vascular health.

• Avoid Smoking: Smoking can impair circulation and increase oxidative stress, exacerbating glaucoma risk.

• Limit Caffeine: High caffeine intake may transiently elevate IOP.

Educating Patients and Preventing Vision Loss

Healthcare professionals should use patient inquiries as opportunities to educate them about the complexities of glaucoma and the importance of managing systemic health. By fostering a collaborative approach, patients become more engaged in their care, which can lead to better adherence to treatment plans and monitoring schedules.

Emphasizing the importance of regular eye examinations, adherence to glaucoma medications, and monitoring systemic blood pressure can help prevent disease progression and preserve vision.

Conclusion

The relationship between blood pressure and intraocular pressure is multifaceted, with both high and low blood pressure potentially influencing glaucoma risk and progression. While high blood pressure may contribute to increased IOP, low blood pressure can reduce ocular perfusion pressure, leading to optic nerve damage.

Healthcare providers should address patient concerns by providing clear explanations and individualized recommendations. Collaborating with patients to manage both ocular and systemic health is essential in preventing vision loss due to glaucoma.

References

• Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Honkanen R, Nemesure B. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):85-93.

• Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. Vascular risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma: the Egna-Neumarkt Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1287-1293.

• Choi J, Kim KH, Jeong J, Cho HS, Lee CH, Kook MS. Circadian fluctuation of mean ocular perfusion pressure is a consistent risk factor for normal-tension glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(1):104-111.

Note: This information is intended for educational purposes and should not replace professional medical advice. Patients should consult their healthcare providers for personalized guidance.

(1).jpg)