Study Reveals Complex Muscle Patterns Behind Blinking and Eyelid Movement

Blinking may seem like a simple, instantaneous reflex, but the mechanics behind it are far more intricate. Without proper eyelid function, the eye can become dry, irritated, and eventually lose clear vision. Now, a team of UCLA biomechanical engineers and ophthalmologists has mapped the detailed activity of the muscle responsible for blinking, paving the way for advanced blink-assisting neuroprostheses.

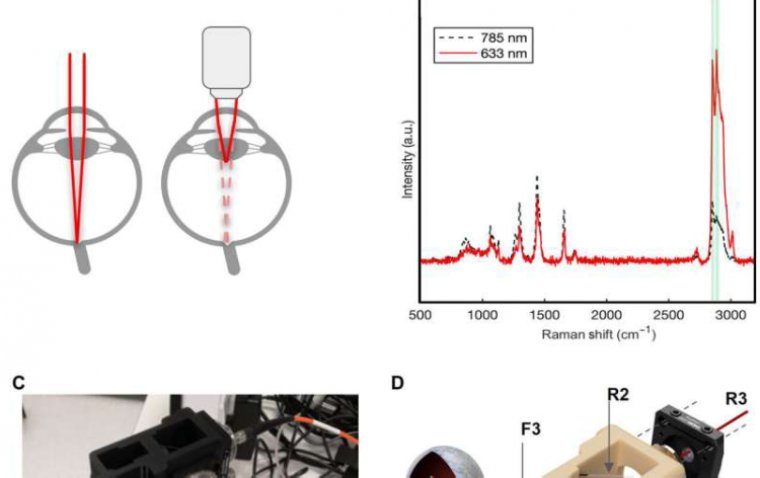

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focused on the orbicularis oculi muscle, which controls eyelid movement. Researchers found that this muscle contracts in complex, action-specific patterns, moving the eyelid in more than just a simple up-and-down motion.

“The eyelid’s motion is both more complex and more precisely controlled by the nervous system than previously understood,” said Tyler Clites, PhD, corresponding author and assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. “Different parts of the muscle activate in carefully timed sequences depending on what the eye is doing. This level of muscle control has never been recorded in the human eyelid. Now that we have this information in rich detail, we can move forward in designing neuroprostheses that help restore natural eyelid function.”

Five Distinct Types of Eye Closure

The research examined how the orbicularis oculi behaves in five different eyelid closure types:

1. Spontaneous blink – an unconscious blink that naturally lubricates the eye.

2. Voluntary blink – an intentional blink, such as when blinking on command.

3. Reflexive blink – a rapid, involuntary blink triggered to protect the eye from impact.

4. Soft closure – a gentle, slow descent of the eyelid, like falling asleep.

5. Forced closure – a deliberate squeezing of the eyelids tightly shut.

High-Precision Mapping of Eyelid Muscle Activity

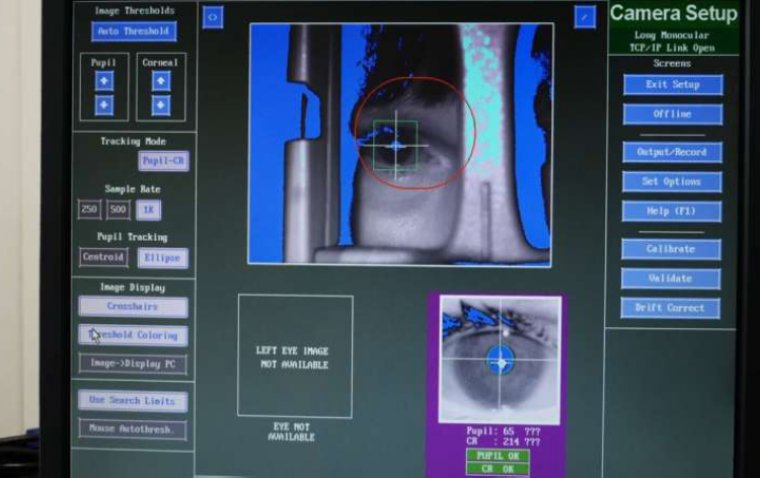

To measure muscle activity with high accuracy, an ophthalmic surgeon inserted tiny wire electrodes into the eyelid. Using a motion-capture system to record movement in ultraslow motion, the team tracked the eyelid’s speed, direction, and the exact muscle regions initiating each closure type.

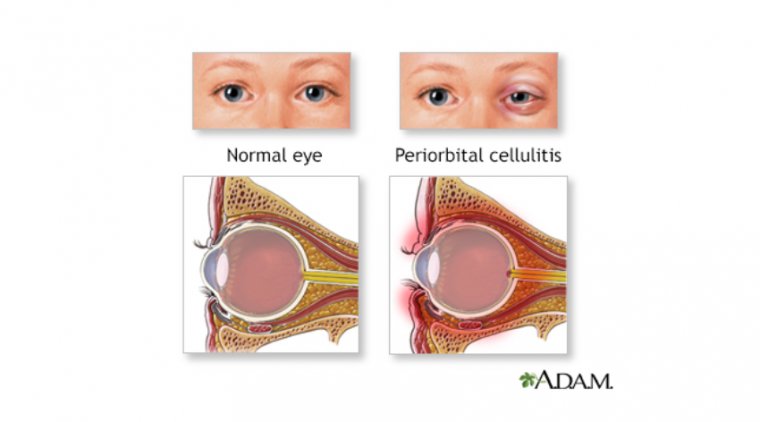

“People can lose the ability to blink due to stroke, tumor, infection, or injury,” explained Daniel Rootman, MD, study co-author, associate professor of ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and director of the UCLA Orbital Disease Center. “The condition is painful in the short term and can damage the eyes enough to cause vision loss. We know that a small electric pulse can stimulate the orbicularis oculi, but designing one that works well has been elusive. What we now have is a roadmap—including electrode placement, timing, and pulse strength—that could pave the way for developing and testing a blink-assisting device.”

Towards a Blink-Restoring Neuroprosthesis

With this biomechanical data, the team can now refine prototype neuroprostheses for patients who have lost blinking ability, such as those with facial paralysis.

“Understanding how the eyelid works is crucial to designing an accurate stimulation pattern for a prosthesis, as well as for diagnostic purposes,” said Jinyoung Kim, study first author and UCLA mechanical engineering doctoral student. “We are excited to bridge this gap and work directly with patients to help improve their lives.”

The ultimate goal is to restore natural, comfortable blinking in individuals who can no longer close their eyes, thereby preserving eye health and vision.

Reference:

Jinyoung Kim et al, Human eyelid behavior is driven by segmental neural control of the orbicularis oculi, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2508058122

(1).jpg)