The Connection Between Blood Pressure and Glaucoma

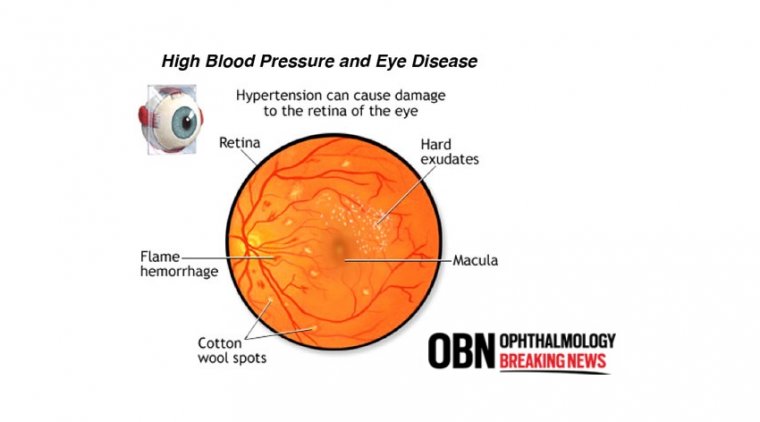

Eye pressure varies separately from blood pressure. IOP management is not the same as blood pressure control. However, research has shown that those with high blood pressure are more likely to develop glaucoma. Glaucoma is not aided by extremely high blood pressure.

Low blood pressure, which must be moderate to extremely low for the visual nerve to receive enough blood flow, is another issue. Low ocular perfusion pressure appears to be a significant risk factor for glaucoma, according to the evidence.

The differential between blood pressure and eye pressure can be thought of as the ocular perfusion pressure, a complex quantity. Blood has trouble getting into the eye to deliver oxygen and vital nutrients if the blood pressure is low and the eye pressure is high.

Patients with high blood pressure who take medication may actually experience very low blood pressure readings when they are sleeping. Due to reduced blood flow to the eye and optic nerve, the optic nerve may become compromised.

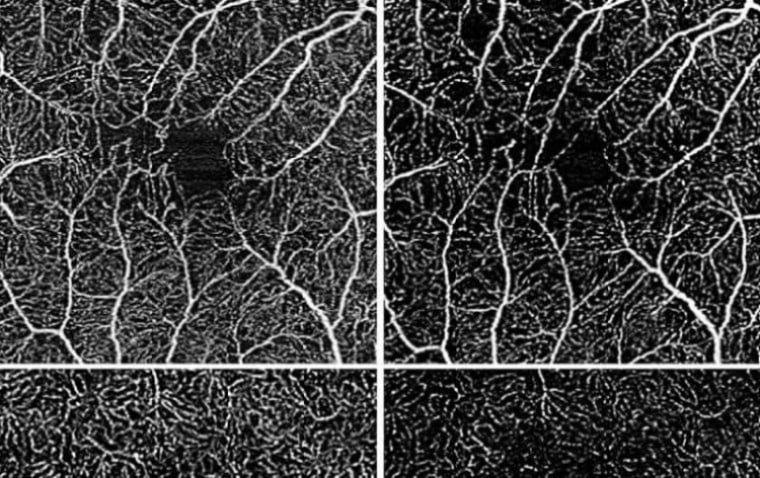

Research on how blood flow affects optic nerve injury is underway. We now know that there is a direct correlation between various types of glaucoma and decreased blood flow to the optic nerve.

Although intraocular pressure (IOP) continues to be a significant risk factor for glaucoma, it is obvious that additional factors can significantly affect the onset and progression of the condition.

Blood pressure (BP) is a clinically modifiable risk factor for glaucoma that has gained interest more lately because it offers the potential for new therapeutic approaches beyond IOP reduction.

The ocular perfusion pressure (OPP), which controls the flow of blood to the optic nerve, is determined by the interaction between blood pressure and IOP.

Hypotension should enhance the negative consequences of IOP rise, whereas hypertension should protect against IOP elevation if OPP is a more significant factor in determining ganglion cell injury than IOP.

Conflicting conclusions about the contribution of systemic hypertension to the onset and progression of glaucoma are drawn from epidemiological studies. According to the most recent study, glaucoma is more common in persons with blood pressures at both extremes.

It makes sense that those with low blood pressure would have less OPP and hence less blood flow, but it is more challenging to explain why people with high blood pressure also exhibit elevated risk.

This results might be the result of chronic hypertension-related intrinsic blood flow dysregulation, which would make retinal blood flow less resilient to changes in ocular perfusion pressure.

Glaucoma is not a systemic disease in and of itself, however it is known to have systemic risk factors. The vasculature of the optic nerve itself plays a significant role in the interaction between glaucoma and the human system.

Similar to other cells, the approximately 1 million ganglion cells that form the optic nerve must both breathe and consume in order to survive. Even while it oversimplifies the two processes, it is still largely true.

For respiration and glucose supply, which are both necessary for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the visual nerve cells rely on the circulatory system. Therefore, anything that harms the circulatory system has the potential to harm the visual neurons by definition.

Risk Factors

For instance, openangle glaucoma has long been linked to diabetes mellitus as a risk factor. There may be more evidence than ever before to support this.

Having said that, the connection between blood pressure and glaucoma has been researched for a long time. Particularly in so-called "normal tension" glaucoma, low blood pressure has been connected to the emergence of open-angle glaucoma.

It is appropriate to assess the connection between blood pressure and glaucoma and consider the role of optometrists in light of the recent publication of revised blood pressure guidelines established by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.

Supporting Research

An investigation conducted in 2018 and published in the American Journal of Hypertension found a nonlinear association between the existence of glaucoma and systemic blood pressure. The researchers of the study concluded that the two have a U-shaped association.

This indicates that both patients with low and high blood pressure saw a rise in the incidence of glaucoma. 4,137 adults aged 40 or older who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from 2005 to 2008 were included in the study.

In the study sample as a whole, glaucoma prevalence was 1.2%. Separate metrics were used to assess the association between these two chronic diseases: systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

For participants who did not take antihypertensive drugs, both high systolic blood pressure (more than or equal to 161 mm Hg) and low systolic blood pressure increased the risk of glaucoma (less than or equal to 110 mm Hg).

Similar to how high and low diastolic blood pressure increased the risk of glaucoma (greater than or equal to 91 mmHg or less than or equal to 60 mmHg, respectively).

Participants in the research with systolic blood pressure between 11 mm Hg and 120 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure between 81 mm Hg and 90 mm Hg had the lowest prevalence of glaucoma.

This study implies that in terms of glaucoma, a blood pressure "Goldilocks scenario" in which there is an ideal range is recommended.

Low blood pressure can cause ischemia to the optic nerve and decrease ocular perfusion pressure, either naturally or as a result of over-treating hypertension. This aspect might be particularly important in the context of normal tension glaucoma.

On the other hand, systemic hypertension frequently results in arteriosclerosis, which may reduce blood flow to the optic nerve even if it may not be harmful in the short term.

Controversial Link

Systemic hypertension and glaucoma have always had a contentious connection. In fact, the 2008 Barbados Eye Studies revealed a possible link between systemic hypertension and a lower incidence of glaucoma.

The development of ocular hypertension is thought to be influenced by systemic hypertension, according to more recent research that was published in 2014.

Putting Into Practice

The question then comes as to what eyecare professionals can do with this knowledge given that modern research suggests that a range of blood pressure that is not too high and not too low is ideal for the patient.

If optometrists are not already doing so, taking a patient's blood pressure as part of a glaucoma evaluation is a simple and painless technique to determine whether or not a different risk factor for the condition exists.

It is wrong to presume that just because a patient is taking an oral antihypertensive drug, his blood pressure is "managed". In actuality, taking oral antihypertensives is a frequent contributor to hypotension.

Nonselective beta blockers, such timolol (Timoptic, Betimol; Alcon), are known to have systemic hypotension and bradycardia in their medication side effect profiles, in addition to the fact that low blood pressure might contribute to glaucoma.

Optometrists who treat glaucoma patients can monitor patient safety and potential lurking factors by keeping an eye on measurements like systemic blood pressure.

(1).jpg)