Living Contact Lens Uses Lubricant-Producing Bacteria to Combat Dry Eye

Researchers have developed a new type of contact lens that contains a community of lubricant-producing bacteria to combat contact lens-associated dry eye, a common issue that leads many to discontinue use.

The findings were published in Advanced Materials.

Innovative Solution to a Common Problem

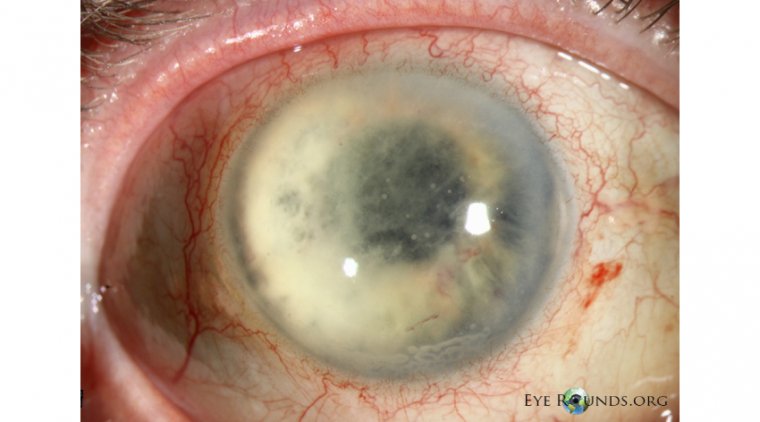

For many, contact lenses are a preferable alternative to eyeglasses. However, they disrupt the eye's tear film, causing friction and dry eye. "Contact lens-associated dry eye prevents contact lens wear and limits wear time," explained Aránzazu del Campo, scientific director and CEO of the INM-Leibniz Institute for New Materials in Germany. Patients often need to apply eye drops continuously to restore the liquid and lubricant film on the contact lens surface.

Bacterial Biofactories for Lubrication

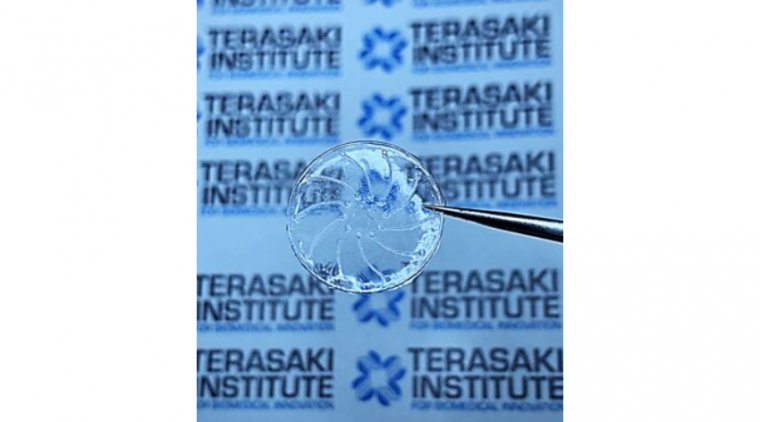

The solution comes in the form of bacterial biofactories embedded in the rim of the self-lubricating lenses, as described in the recent study. These bacteria are engineered to continuously produce hyaluronic acid, a natural lubricant that provides more durable relief than eye drops. "The lubricant diffuses from the bacteria to the contact lens surface," said del Campo, adding that this process provides permanent lubrication despite the continuous clearance by tear fluid.

Why Use Bacteria?

The bacteria used, Corynebacterium glutamicum, is a harmless species recognized as safe by the FDA. It's a workhorse in biotechnology, used in various industries, from food flavorings to pharmaceuticals, and here, it's engineered to secrete hyaluronic acid. This choice was also influenced by its relation to C. mastitidis, a natural resident of the human eye microbiome.

In the study, the bacteria obtained nutrients from simulated tear fluid, but in a commercial product, they would get nutrients from the wearer’s tears and overnight lens care solution. "Hyaluronic acid production and therefore lubrication is maintained for weeks," del Campo stated.

Skepticism and Future Research

While the technology is promising, optometrist Meenal Agarwal, not involved in the study, expressed skepticism about widespread acceptance due to potential safety concerns with live bacteria in contact lenses, especially for immunocompromised individuals. Del Campo acknowledged these concerns, noting that further research is needed to establish safety and address any potential issues. "Our analysis shows that the living contact lens is not harmful to cells; [Live] studies are needed to rule out irritation or other problems," she said.

Future studies will also help understand variables like bacterial density and nutrient concentration, crucial for ensuring the lens's effectiveness and safety.

The final challenge will be consumer acceptance. While some may prefer traditional methods, others may view the self-lubricating, living contact lens as a long-awaited solution to an irritating issue.

Reference: Aránzazu del Campo, et al., Self-Lubricating, Living Contact Lenses, Advanced Materials (2024). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202313848

*Stay in the loop and make sure not to miss real-time breaking news about ophthalmology. Join our community by subscribing to OBN newsletter now, and get weekly updates.

(1).jpg)