General Anesthesia – Surgery & Fasting

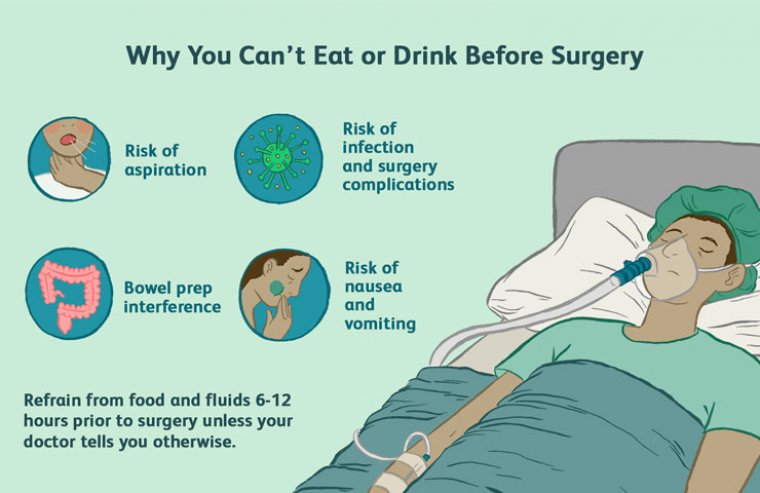

Why You Should Fast Before Surgery?

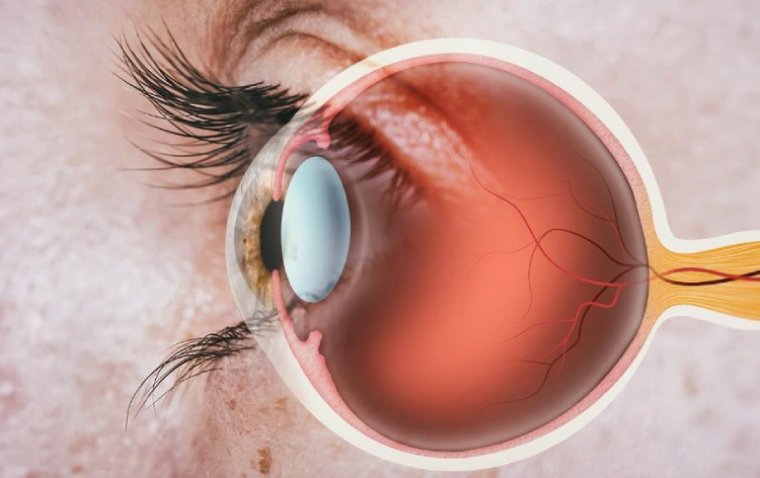

Usually, before having a general anesthetic, patients are not allowed anything to eat or drink. This is because when the anesthetic is used, the human body’s reflexes are temporarily stopped.

If a patient’s stomach has food and drink in it, there’s a risk of vomiting or bringing up food into the throat. If this happens, the food could get into the lungs and affect breathing, as well as causing damage to the lungs.

While some may argue that fasting is a necessity, that may not be true. The requirement for fasting before surgery was recommended by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), which published updated guidelines in 2011 for patients undergoing general anesthesia to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

What Happens If You Vomit Under Anesthesia?

General anesthesia is the key consideration because, in its absence, there is little risk of aspiration pneumonia, except upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; in those receiving light sedation, postoperative nausea and vomiting also are rare. Finally, fasting does not guarantee gastric emptying, according to Daniel Terveen, MD.

The need that older patients scheduled for cataract surgery fast changes their typical routine, which may have an impact on individuals with diabetes or other comorbidities and increase their risk of dehydration, changed blood glucose levels, and substantial stress.

Analyzing Cases

Terveen, along with a group of colleagues that included Chris Bender, CRNA, conducted a study to determine how the absence of preoperative fasting affected patient satisfaction with the surgical experience. Both Terveen and Bender are with Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

A total of 200 patients who received oral sedation before undergoing routine cataract surgery were included in a prospective case-control study. Half the patients followed the ASA fasting guidelines, and 100 patients were not required to fast— to determine the patient levels of comfort and the postoperative incidence rates of nausea and vomiting.

The postoperative patient satisfaction was scored on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating very dissatisfied and 5 indicating very satisfied. “The preoperative and postoperative scores were both very high in the fasting and nonfasting groups, but we found a clinically significant difference in the preoperative satisfaction levels between the groups,” Terveen said.

“The patients who did not fast preoperatively had a better experience by maintaining their normal routines and were not as concerned about the effects of stopping their medications.” One episode of nausea and vomiting occurred in each group, and no aspiration occurred in either group.

The researchers came to the conclusion that removing the need for preoperative fasting had no adverse effects on aspiration or nausea and vomiting during surgery.

The surgeon places it close to the ciliary body and under the iris, where the inflammatory cascade starts, rather than having to traverse the corneal and conjunctival barriers. When we took part in the Dexycu clinical studies, we observed how tranquil the anterior chambers seemed following surgery, with virtually any cell or flare on the first postoperative day.

We ascribe this to both the timing and the injection site. The reality is that family members may still need to go to the pharmacy or the patient may go home and fall asleep before instilling the drops, even though we advise the patient to use topical drops 4 times a day beginning several hours after surgery or the next morning if the eye is patched at the time of surgery.

In contrast to the few seconds it takes for the surgeon to inject Dexycu after the case, it can take anywhere between 12 and 24 hours or more before the first dosage of topical steroid is administered to the eye.

There is a bit of a learning curve for the proper injection technique for Dexycu; there is also the possibility of migration of the dexamethasone spherule onto the IOL optic or onto the iris, where it becomes visible until its absorption within a few days.

With intraoperative sustained-release steroids— perhaps coupled with other injected or sustained-release drugs—we can eliminate the gambles of patient adherence. This has the potential to greatly enhance the patient experience, improve practice flow, and provide the surgeon with more control over unwanted postoperative complications.