Glaucomatous Optic Nerve Damage

The optic nerve is composed of approximately 1.5 million nerve fibers at the back of the eye that carry visual messages from the retina to the brain. When light hits the retina, the photoreceptors (light-sensitive cells) receive and transmit this information to other specialized cells, including the final cell type in the chain, called the retinal ganglion cells.

The Retinal Ganglion Cell - Key Player in Visual Information Transmission

These retinal ganglion cells reside in the retina, but their output “cables” or “fibers,” called axons, extend from the head of the optic nerve at the back of the eye to the brain. Therefore, the retinal ganglion cell plays a critical role as the output nerve cell of the eye that transmits visual information to the brain.

Visualizing the Optic Nerve - Insights from Eye Examinations

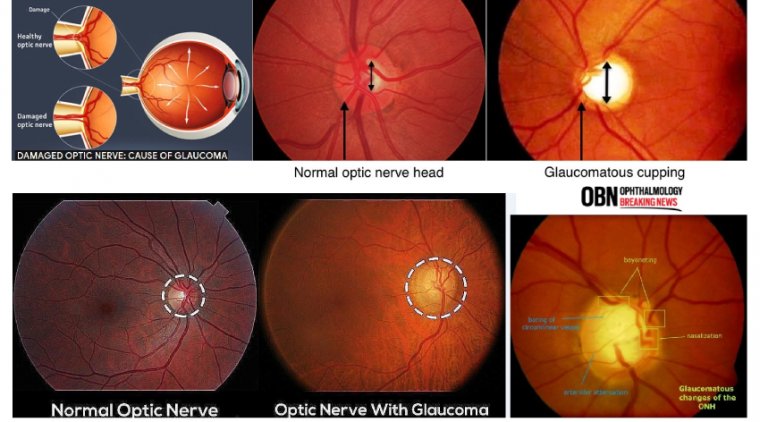

When the eyes are examined, the optic nerve is actually visualized by the eye doctor with the help of special lenses. The axons of the optic nerve are bundled and insert in the back of the eye, and this “optic disc” is seen in the back of the eye along with blood vessels.

Exploring Glaucoma and its Relation to Optic Nerve Damage

In optic nerve degeneration related to glaucoma, the optic disc displays changes that are characteristic of glaucoma, which your doctor may refer to as “cupping.” While considering glaucoma, focus historically has been on intraocular pressure (IOP). But other types of pressures are involved and should be on optometrists’ radar, according to Mark T. Dunbar, OD, FAAO, director of optometric services, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Health System, Key Largo, Florida.

Beyond Intraocular Pressure - Understanding Additional Risk Factors

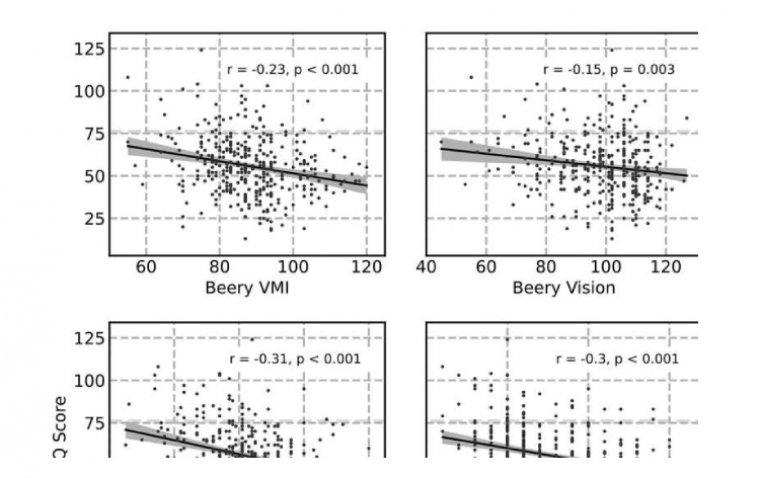

Dunbar explained that while the general principles for managing patients with glaucoma seem straightforward—the higher the IOP, the greater the risks are of both glaucomatous damage and disease progression—other factors contribute to optic nerve damage and determine an individual’s susceptibility to damage from IOP.

Factors Contributing to Glaucoma

Many patient scenarios are not straightforward. For example, Dunbar posed, some patients with high IOPs do not have glaucoma and have normal optic nerves with ocular hypertension.

Things to Watch - Blood Pressure

Investigators suggested 3 decades ago that systemic hypotension and decreases in nocturnal blood pressure were instrumental in glaucoma progression. A combination of lowest blood pressure levels and the highest IOP levels at night are risk factors for disease progression.

Ocular Perfusion Pressure

OPP is defined as the relative pressure at which blood enters the eye, or the ocular arterial pressure minus the IOP. Low OPP is a risk factor for progression resulting from low blood pressure and/or high IOP, he said. The relationship between OPP and glaucoma, however, has not been confirmed.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Pressure

Two retrospective studies conducted by John Berdahl, MD, in 2008, included close to 100,000 patients who underwent a lumbar puncture. Of those who underwent an ocular examination, 217 had primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). In the first study, authors concluded that intracranial pressure was significantly lower in patients with POAG compared with controls without glaucoma.

Considering Other Risk Factors for Glaucoma Development

The cumulative 20-year information gleaned from the all-important Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study indicated that approximately 30% of patients develop glaucoma over 20 years and various risk factors can increase that percentage significantly, such as older age, thinner cornea, and higher IOP.

The Future of Glaucoma Management

As our understanding of glaucoma deepens, it becomes evident that multiple factors contribute to the disease. While IOP remains a treatable factor, research continues to explore other aspects that may play a significant role in the management and prevention of glaucoma.

(1).jpg)